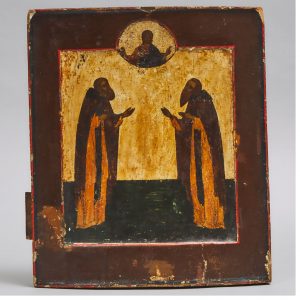

Icons play an integral role in Russian culture as well as in the Eastern Orthodox liturgy. An apocryphal story explains that Saint Luke the Evangelist painted the first icon, which was then blessed by the Virgin Mary before eventually ending up in Russia. Icons were hung not only in the church but in every Eastern Orthodox home, regardless of wealth or standing. The role of the icon was manifold, and was used alternately as a means of communion with the divine, a witness before which one swore oaths, as well as a talisman to be carried into battle.

Russian icons were intended to function as a window to guide the faithful into the spiritual realm, and were traditionally hung across a corner of the house. The krasny ugol, the “red” or “beautiful” corner typically faced east, towards the rising sun, as it was believed that Christ would return to Earth from this direction. These corners are considered the spiritual heart of the home, and facing into these corners was intended to eliminate the distractions of the house and concentrate one’s prayers. When the icon was too worn down, it was given a solemn burial at land or at sea.

An interesting perspective

Russian icons can be differentiated from their Western counterparts in part due to their use of ‘reverse perspective.’ If you have ever looked at art from the Middle Ages and wondered why it looks so off-kilter, this is why. Reverse perspective places the vanishing point not within the painting in the realist or linear manner, but instead gives the illusion that it is in front of the painting. Objects diverge towards the horizon rather than converge: imagine driving down an open road that gets wider rather than narrower as you look off into the distance. This technique is also referred to as Byzantine perspective, as the convention was imported into Russia from the Byzantine Empire when the nation adopted the Orthodox Christian religion in the late 900s.

Regan Denarde Shrumm explains that “icons deliberately avoided a naturalistic look, but instead symbolized the bodies of the saints since, as Saint Paul explains, “the glorified body is not like the earthly body.”” He continues, noting that “according to Eastern Orthodox theology, icons are not merely depictions of a saintly person, but instead are believed to convey the presence of the figure depicted.”

Unlike Western Europe, Russia did not participate in the Renaissance, staying in the Middle Ages from the 10th century until the ascension of Peter the Great in the 17th century. Peter implemented a cultural revolution to radically overhaul Russia, replacing the old ways with modern, Westernized ideals based in science and the Enlightenment. However, though Russian icon painters were made aware of the linear perspective, it was not adopted into this artform as the avoidance of naturalism was intentional. The reverse perspective was intended to create an image beyond logic, to impose a cosmic scale appropriate for a sacred image.

15 x 12 in — 38.1 x 30.5 cm

Estimate $400-$600

Traditions and repetition

Icons were traditionally made only by the extremely devout, and would have to be blessed before leaving the artist’s studio. The brushes and tools used to construct these images would also need to be blessed, which is why many icons were made by monks. Icons were never signed, as “each was considered equally good, equally spiritual, and not a work of art.”

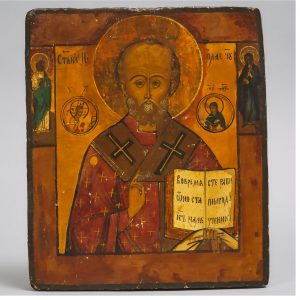

Important icons were often copied, as there was a belief that the power and luck of the original would infuse the duplicate image. Manuals were produced to describe which imagery corresponded with each scene or subject, and colours, poses and inscriptions were typically prescriptive. These details also served to help viewers identify the characters in the scene and understand the message being conveyed.

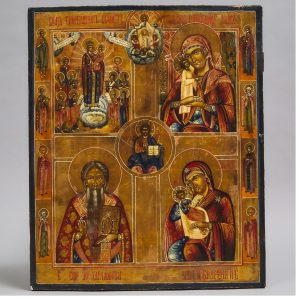

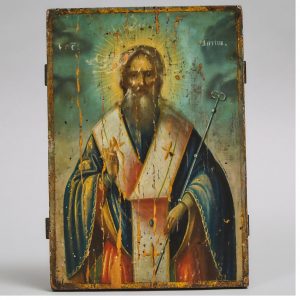

Some scenes are known as “hagiographic” icons, which depict the life of a saint from birth to their canonization. If an icon contains multiple vignettes or a narrative, they are conventionally intended to be “read” just like the page of a book: top left to top right, top to bottom. Figures are scaled according to their importance, with major figures larger than minor characters. Some icons are set against very minimal backgrounds, so as to amplify either the isolation of the subject’s suffering or their importance, absented of any distracting or superfluous details.

Russian icons were painted in layers, beginning with a dark brown background. Forms were delineated using reddish ochres and white lead. Gold and gilding were employed to symbolize the light of the heavens. When gold was out of reach, the colour yellow was used as a stand in. Irina Osipova notes that the colour grey was never used, as the mixing of black (evil) and white (good) was seen as inappropriate and “the colour of uncertainty and emptiness.”

FIND OUT MORE about the auction

We invite you to browse a selection of Russian icons from the 17th to 19th centuries in our February Decorative Arts & Design auction. The auction will be online from February 13-18.

Please view the full auction gallery here.

Should you have any questions or would like additional images or information, please do not hesitate to contact Sean Quinn at [email protected] or by telephone at 416-847-6187.

Estimate $800-$1,200

Estimate $600-$800

Estimate $300-$500

Related News

Meet the Specialist

Sean Quinn

Senior Specialist, Clocks, Sculpture & Lighting