Waddington’s is honoured to be featuring three lots of pottery by the acclaimed 20th century artist Beatrice Wood (1893-1998) in our upcoming auction Studio Ceramics: The Paul Duval Collection – Part III. Beatrice Wood was best known for making pottery with singular authenticity and unusual beauty, accentuating hand-made forms with striking lustre glazes achieved with a complex and highly volatile firing process. These favourable qualities also shone through in Wood’s personality: her many friends and her own writing reveal a generous spirit and deep curiosity for life and art that would lead her down many creative avenues before she discovered her artistic talents with clay.

Though she came from a wealthy American family, Wood was a born bohemian who, in her own words, craved ‘danger, adventure, and love.’ Growing up, she was often in conflict with her mother’s aristocratic ideals and luxurious lifestyle. Wood dreamt of being an artist, a path she would follow when she ran away from home at the age of 16. Her reserved mother was so scandalized by her daughter’s choices that she repeatedly threaten suicide. In her autobiography, I Shock Myself, Wood recalls being forced to leave France–where she was studying the theatre–to go home to America at the outbreak of World War I. She desperately wanted to stay and assist France in their war efforts, but her caretakers insisted she return to safety. In a carriage on the way to her ship, she describes being stopped by troops several times “… breathlessly, I gazed out of the window hoping a soldier would grab me and try to get secrets from me, as if I were a spy. To my disappointment, nothing happened.”

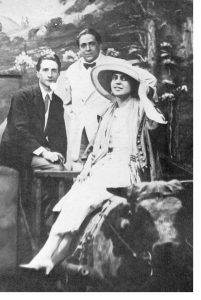

In an era when women faced many limitations, Wood’s uncompromising determination and passionate spirit led her to seek personal and creative freedom, sometimes by extraordinary means. She would eventually forgo the financial security offered by her family in favour of pursuing a more free-spirited artistic path, living on her own terms. In New York in the 1910s, she enjoyed a successful career as a dancer and actress, rubbing elbows with Isadora Duncan, Anna Pavlova, and Vaslav Nijinsky, among other notable figures. It was during this period that she embarked on her most famous love affairs–many of which would morph into affectionate lifelong friendships. The first great love of her life was French writer and scholar Henri-Pierre Roché. Roché was also a notable art collector, being an early patron of Picasso, George Braque and Constantin Brancusi, as well as a close friend and confidant to avant-garde artists including Marcel Duchamp, who Wood would also fall in love with. Wood and Duchamp were fast friends, and Duchamp encouraged her to explore the visual arts, offering her space in his studio where she could work. Wood explained that “Roché thought it was wonderful that I had this opportunity to work with [Duchamp] and encouraged me to go to his studio as often as possible. He even teased me about being in love with Marcel. Instead of being jealous, he was delighted when I told him I dreamt of Marcel. For Roché loved Marcel too, as I think everyone who met him did.”

Duchamp and Roché both enjoyed developing Wood’s artistic sensibilities. They were disinterested in the theatre and wanted her to concentrate on creating art instead. In his senior years, Roché wrote Jules et Jim, a novel-turned-film about a woman who loved two men, loosely portraying the real love triangle between him, Wood, and Duchamp at that time.

Wood also met Louise and Walter Arensberg, who would become lifelong friends and mentors. The Arsenbergs were avid supporters of avant-garde art and would frequently host evenings with a variety of artists in their New York apartment, which was packed floor-to-ceiling with modern art which most people at the time considered hideously distasteful. Their taste would prove to be good, as a wing would be dedicated to their collection at the Philadelphia Museum in the 1950s. In her book, Wood mused on these evenings, writing that “night after night they gathered around the grand piano and carried on fascinating and knowledgeable discussion on every imaginable subject. All of the artists of New York were found there sooner or later…” The Arsenberg Circle of Artists would be responsible for the historical ‘First Exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists,’ a non-juried art exhibition open to anyone, an unprecedented concept at the time. It was for this occasion that Duchamp submitted his infamous Fountain (the ‘readymade’ urinal) under the pseudonym R. Mutt. Wood recalls Walter Arsenberg and fellow organizer George Bellows arguing hotly over this submission, which they ultimately denied for being against the exhibition’s principals. Afterwards, Wood, Duchamp and Roché would write and publish “The Blind Man” magazine, which spread the word about the exhibition’s controversial submission and subsequent hypocrisy. With this project, Wood recalls their excited and mischievous camaraderie, noting that Duchamp was “greatly amused, but also felt it was important to fight bigotry in America.”

While it would appear that Wood had already lived a full and fascinating life by the end of her twenties, it was in her 40s that she would discover the art practice for which she would become famous. At that time, she was living in California pursuing the philosophical and spiritual teachings of Jiddu Krishnamurti. Somewhat on a whim, she began taking pottery classes. After purchasing some lustre glazed plates while traveling in Holland, she so badly wanted a matching teapot that she decided she’d learn to make it herself, which she thought would be a quick endeavor. Though she claims she was not very good to start, she quickly became fascinated with the craft and decided to pursue it with full force. Initially, Wood saw it as a means to earn some income in the midst of the Great Depression, though over time her enjoyment of and dedication to her practice led her to realize this as her calling. Integrity was important to her creative work, and during a period when she was living on the verge of poverty, she recalls turning away substantial commissions because the requests did not align with her vision. Once, she reluctantly agreed to take a commission from a very wealthy patron to produce a design that was not hers on the basis that she would not sign her name to it, but after having a terrible nightmare about it, she withdrew her acceptance.

Eventually, Wood was able to scrape together enough money to fulfil a long-held dream of building her own pottery studio and home in Ojai. Here, she would pass the rest of her life in artistic contentment, running her own shop, teaching ceramics at the Happy Valley School, and honing her skills– particularly in the realm of glazes. In the documentary film Beatrice Wood: the Mama of Dada, Garth Clark, ceramics historian and dealer, comments “What Beatrice is, in effect, is an alchemist. She takes mud, and she turns it into golden vessels that could grace the table of a maharaja.” This is in reference to the method she used most often called reduction firing, which produces lustre effects in pottery glaze. Through this process, oxygen is removed from the kiln, driving all the metallic salts and iridescence to the surface of the glaze. Entering the kiln, the glazes appear thick, gray, and opaque: the highly variable outcome depends on many subtle chemical factors. According to Clarke, it is a “very difficult and unpredictable art with relatively few masters over the history of time.” Wood’s attitude on the subject was less scientific and more wonderstruck: trying to draw a comparison, she once declared that “women who have diamonds– it can’t touch the joy and excitement of opening a kiln.” In experimenting with glaze formulas, she kept detailed records of every piece made, and though it was not possible to re-create effects, she cites her continuous efforts as the most important factor in her success.

Wood’s life continued to inspire others, with James Cameron basing the character of Rose in Titanic on her. It has been a pleasure to learn more about the vibrant woman behind the pottery, and we invite you to take a look at lots 305, 329, and 330 in our Studio Ceramics: The Paul Duval Collection – Part III auction: three fine examples of Wood’s work in the 1980s, created while she was at the height of her career in her 90s.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

We invite you to view the full online gallery for this auction, online from May 8-13, 2021. Should you require more information or additional images, please contact Bill Kime at [email protected] or by telephone at 416-847-6189, or Hayley Dawson at [email protected].

INTERESTED IN CONSIGNING TO OUR AUCTIONS?

Please contact us to discuss consignment opportunities for our 2021 auctions.

Related News

Meet the Specialists

Hayley Dawson

Associate Specialist (On leave until 2025)

Bill Kime

Senior Specialist, Ceramics, Glass and Silver