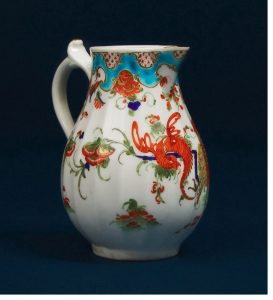

What’s the connection between 17th century Japanese potters and a famous 19th century nonsense poem? Read on for the curious history of Jabberwocky pattern porcelain.

From Japan to Germany to England

Worcester’s ‘Jabberwocky’ pattern has its roots in Japanese Kakiemon porcelain. Kakiemon is a style of Japanese ceramic with brightly coloured overglaze enamel decoration, produced in the area around Arita (modern-day Saga Prefecture, in the very southernmost tip of Japan) from the mid-17th century Edo period onwards. Brought to Europe by the Dutch East India Company, Kakiemon was highly prized, so much so that it was widely emulated by European porcelain manufacturers during the 18th century.

Among these admirers was the pioneering Meissen factory, where artists would make direct copies of Kakiemon designs. They would also borrow these motifs and styles, which they would adapt to suit European tastes. It is thought that the dragon-like bird and rich foliage characteristic of Worcester’s ‘Jabberwocky’ pattern owes much of its inspiration to the Meissen factory, which had in turn been copied and adapted by artisans working there. Worcester’s design is found primarily on teawares produced in the late 1760s and 1770s, then referred to as ‘fine old rich dragon pattern, bleu celeste borders’. It wasn’t until over a century later that the name ‘Jabberwocky’ was adopted by collectors.

Lewis Carroll’s Jabberwocky

Carroll included “Jabberwocky” as a section in Through the Looking-Glass, his follow up novel to Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. The nonsense poem (full text below) is found by Alice, who assumes it is written in an unintelligible language. Upon her realization that she is currently travelling in an inverted world, she comes to understand that the poem is printed in reverse. Using a mirror, she is able to read the text of “Jabberwocky,” though she is unable to make much sense of it:

“It seems very pretty,” she said when she had finished it, “but it’s rather hard to understand!” (You see she didn’t like to confess, even to herself, that she couldn’t make it out at all.) “Somehow it seems to fill my head with ideas—only I don’t exactly know what they are! However, somebody killed something: that’s clear, at any rate.”

Many of the words in the poem are ‘nonce words,’ which means that they were created for a single occasion in order to serve a particular linguistic need. Carroll noted many years later that he himself did not know the meanings of some of the words used in Jabberwocky, but rather that the ambiguity and uncanniness was meant to echo the dreamlike world Alice is travelling in. Regardless of intent, several of Carroll’s inventions have gone on to assume real meaning in the English language, including ‘galumphing’ and ‘chortle.’ Even the term ‘jabberwocky’ itself has come to refer to nonsense language.

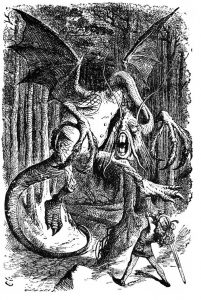

John Tenniel’s dragon

In addition to his writing, Carroll had a passion for the visual arts, and had personally drawn the illustrations for Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. However, when the engraver Carroll had hired to produce the plates needed to print his drawings saw his illustrations, he suggested that they commission a professional instead. This led him to John Tenniel, a humorist, cartoonist and illustrator perhaps best known for his drawings in Punch magazine, of which Carroll was a regular reader.

Tenniel’s illustrations for both Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass have become the definitive images for these books, influencing how audiences have pictured the visual style of the novels for generations. Indeed, Carroll’s poem gives little indication therein concerning the appearance of his mythical beast, providing Tenniel with a wide artistic berth. Scholars have suggested that Tenniel’s interpretation of the Jabberwock might unconsciously reflect Victorian interests in natural history, specifically paleontology. Between these contemporary concerns and the enduring fascination with Arthurian legends in art and popular culture, the dragonesque appearance of the Jabberwock might have been less of a visual leap and more of a no-brainer.

Audiences were so captivated by Carroll’s poem and by Tenniel’s illustrations that the books became a cultural touchstone. Though it is unknown who was the first porcelain enthusiast to make the link between Worcester’s pattern and Carroll’s poem, regardless, the name stuck. One hundred years later, collectors around the world still search high and low for this charming pattern with the literary connection. We are pleased to offer an example, a sparrow beak fluted cream jug, c.1770-75, in our special Orkin Collection auction…to which we say: O frabjous day! Callooh! Callay!

About the ORKIN COLlECTION AUCTION

We invite you to view the full online gallery for this auction, online from September 25 – 30, 2021.

The Lois Ruth Orkin Collection of 18th century English porcelain, much of it documented and exhibited at the Art Gallery of Toronto (1962), the Royal Ontario Museum (1968), and at the Gardiner Museum (1986), including good selections and some rare examples of blue and white and polychrome Worcester porcelain, Caughley, Bristol, Limehouse, Lowestoft, Chelsea, Derby, Liverpool and Bow, along with later English and Continental ceramics.

We also invite you to browse the gallery for our Decorative Arts & Design auction, also online from September 25 – 30, 2021.

Should you require more information or additional images, please contact the Decorative Arts & Design department at [email protected] or by calling 416-504-9100 or toll-free 1-877-504-5700.

INTERESTED IN CONSIGNING TO OUR AUCTIONS?

Please contact us to discuss consignment opportunities for our auctions.

Jabberwocky

By Lewis Carroll

’Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe:

All mimsy were the borogoves,

And the mome raths outgrabe.

“Beware the Jabberwock, my son!

The jaws that bite, the claws that catch!

Beware the Jubjub bird, and shun

The frumious Bandersnatch!”

He took his vorpal sword in hand;

Long time the manxome foe he sought—

So rested he by the Tumtum tree

And stood awhile in thought.

And, as in uffish thought he stood,

The Jabberwock, with eyes of flame,

Came whiffling through the tulgey wood,

And burbled as it came!

One, two! One, two! And through and through

The vorpal blade went snicker-snack!

He left it dead, and with its head

He went galumphing back.

“And hast thou slain the Jabberwock?

Come to my arms, my beamish boy!

O frabjous day! Callooh! Callay!”

He chortled in his joy.

’Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe:

All mimsy were the borogoves,

And the mome raths outgrabe.

Related News

Meet the Specialists

Bill Kime

Senior Specialist, Ceramics, Glass and Silver

Hayley Dawson

Associate Specialist (On leave until 2025)