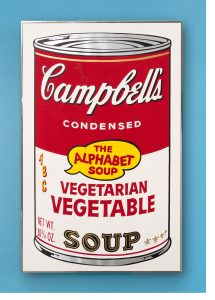

Andy Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Cans might be the most defining image not only of the artist’s oeuvre but of the entire Pop Art movement. With humour and irony, they are a comment on the mass-production, mass-media and material consumption present in American culture. The dominant artistic style when the Soup Cans were made was Abstract Expressionism, which focused on gestural brushstrokes or large areas of painted colour in order to access the individual, the emotional and the contemplative. In contrast, Warhol and the Pop movement celebrated the mundane, the repetitive, and the commercial. Instead of carrying on the fine art tradition, Pop looked at comic books, movies, tabloids, and advertising—popular culture, where the term Pop derives its name.

32 Varieties

By the early 1960s, Warhol had found success as a commercial illustrator, working with clients like Tiffany & Co. and Dior for close to a decade. However, he wanted to break into the art world proper, and be recognized by museums and critics. In search of a subject, a friend of Warhol’s suggested he depict something that everyone would recognize, “like Campbell’s soup.” The Campbell’s can was a perfect subject, having changed little since the red-and-white label’s debut in 1898. When asked years later why he chose the soup cans, he replied, “I used to drink it. I used to have the same lunch every day, for twenty years … the same thing over and over again.”

Warhol got to work, and traced projections of the cans onto canvas before hand-painting in the colours. He worked carefully to mimic the repetition of mass-media advertising, varying his design only in the wording of the individual varieties of the soup on the label. At the time, Campbell’s sold 32 soup varieties, which is the number of canvases Warhol painted. Campbell’s signature fleur-de-lys border was hand-stamped in order to achieve maximum consistency.

Warhol was aiming for a uniform, machine-like aesthetic which betrayed little trace of the artist. What with his training as a commercial illustrator, he largely achieved that, though a few imperfections and differences can be noticed when the 32 flavours are carefully examined, revealing their hand-made origin.

Despite never having exhibited them, Warhol’s Soup Cans were referenced in Time magazine in May 1962 in the first mass-media article on American Pop. At the time, Pop was just getting started and hadn’t found much traction. The write-up mentions that Warhol is making a series of “portraits” of Campbell’s Soup cans, and was accompanied by an image of Warhol eating soup.

A not-so-grand debut

The Soup Cans were first exhibited by gallerist Irving Blum, owner of the Ferus Gallery. The show—which was Warhol’s first solo painting exhibition—opened on July 9, 1962. Blum displayed the work on grocery store shelves, further blurring the line between fine art and commodity. Blum also recommended that Warhol keep his prices low until the public warmed to this new idea.

The reception to the original batch of Soup Cans was not what Warhol and Blum had hoped. The opening was uneventful, and Warhol himself didn’t even attend. Critics didn’t seem to understand the work, and wondered if art could even be art if it concerned itself with such mundane topics. One critic, writing for the Los Angeles Times, wrote of Warhol that “this young ‘artist’ is either a soft-headed fool or a hard-headed charlatan.” Another art dealer located close to Ferus Gallery began selling actual cans of Campbell’s Soup in his window, advertising them with a sign that read “Do Not Be Misled. Get the Original. Our Low Price – Two for 33 Cents.”

Blum was able to sell five paintings, including one to actor Dennis Hopper. But Blum soon realized that the paintings belonged in a complete set. He managed to buy back the already-sold five, and paid Warhol $1000 for the complete batch of 32. Warhol was delighted, as he’d originally conceived of the series as a set. Keeping the works together turned out to be a stroke of genius. Writing for the BBC, Sara McCorquodale explains that “This made it different; it made it a statement. The work seemed to speak of the spirit of a new America, one that thoroughly embraced the consumer culture of the new decade. Before the end of the year Campbell’s Soup Cans was so on-trend that Manhattan socialites were wearing soup can-printed dresses to high-society events.”

After Warhol’s death, Blum sold the series to the Museum of Modern Art in New York City for upwards of $15 million—talk about a return on investment.

Screenprints and Souper Dresses

The Soup Cans marked a turning point in Warhol’s career. After the show at Ferus, Warhol would reinterpret his Soup Cans as silkscreen prints in his quest to “be a machine.” Silkscreen was a technique that had originally been invented for commercial use, and would become Warhol’s signature medium. Silkscreen helped to further erase any impression of the artist’s touch, and better match the precise designs of the cans. He released two screen print portfolios, Campbell’s Soup Cans I in 1986 and Campbell’s Soup Cans II in 1969. Each contains ten screen prints, which mimic the paintings exhibited at Ferus in 1962. He released the portfolios through Factory Additions, a company created by Warhol to distribute his printed works.

The Soup Cans became one of Warhol’s most famous series, and by 1964, Soup Can prints were selling for $1500 each—about $15,000 USD in today’s money. Warhol’s Soup Can became the ultimate representation of his oeuvre. When gracing the cover of Esquire magazine, Warhol was pictured drowning in tomato soup. Even his autobiography, “The Philosophy of Andy Warhol” borrows Campbell’s iconic white and red graphic punch.

Even the Campbell’s Soup company got in on the craze, introducing the “Souper Dress,” a paper dress printed in Warhol-esque cans. The dresses could be trimmed to the wearer’s preferred length, and only cost $1 and two Campbell’s Soup labels. This further fueled the public’s enjoyment of Warhol’s art, which felt “accessible”—who didn’t have a can of soup tucked away in their kitchen?

About the Auction

Held online from November 18-23, the Editions auction features the S.P. Family Collection, a strong selection of prints by modern masters including Pablo Picasso’s Jacqueline au chapeau noir and Francoise, Marc Chagall’s Couple in Mimosas, and Joan Miró’s Querelle d’amoureux. Alongside this collection are such iconic prints as Andy Warhol’s Vegetarian Vegetable, from Campbell’s Soup II, Henri Matisse’s Portrait de Claude D., Joan Miró’s La Cascada, and Damien Hirst’s Keukenhof (Veil) and Currency Series. Also included are several prints by Sam Francis, a timely addition on the occasion of his centennial, and select works by Canadian artists such as Guido Molinari, General Idea, Micah Lexier, David Blackwood, Alex Colville, Takeo Tanabe and Christopher Pratt.

Please contact us for more information.

Related News

Meet the Specialists

Goulven Le Morvan

Director, International Art, Montreal

Alicia Bojkov

Consignment Specialist, International Art