Lot 49

LAWREN STEWART HARRIS

Additional Images

Provenance:

Walter Klinkhoff Gallery Inc., Montreal

Private Collection, Ontario

Literature:

A.Y. Jackson, “Lawren Harris Autobiographical Sketch” in Lawren Harris: Paintings, 1910-1948 (catalogue), Art Gallery of Toronto, 1948, pages 8 and 10.

Note:

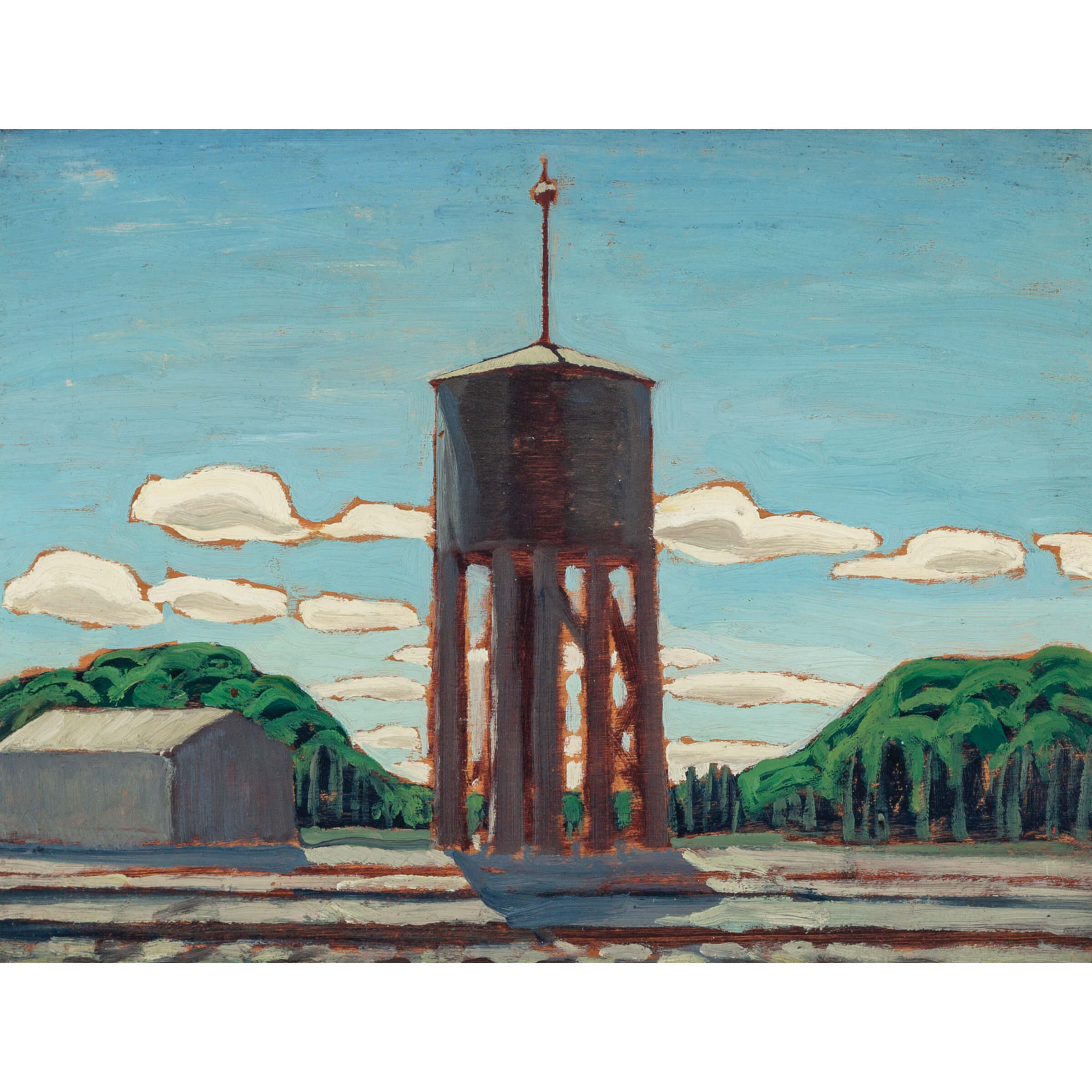

This lot depicts a water tower on the siding of the Algoma Central Railway during one of the infamous “box car” trips which Lawren Harris (1885-1970) arranged for his painting friends.

In the literature of the Group of Seven, particularly the scholarship produced in the early years, one often reads that Algoma was “MacDonald Country”, or that Algoma unsettled Harris, or how Harris struggled with rendering the dense vegetation of the area. It is easy to conclude that the best decision Harris made was to push north to Lake Superior where he would discover the truth of the relationship between subject and meaning. Yet this is a somewhat oversimplified trope, perhaps developed in part to help laymen differentiate between members of the new school of artists that was then emerging. Regional assignments and supposed preferences served a kind of Sykes-Picot arrangement for the Group, carving up Canadian “terroirs” and determining who got what: Algoma was MacDonald’s, Harris won Lake Superior and the Arctic, Quebec belonged to Jackson, Varley covered B.C. and Lismer was awarded the Maritimes.

Yet it is during the first “box car” trips to Algoma, that so much of the thinking that coalesced “the group” into “The Group” actually occurred. (The first Group Show, held in 1920, took place after the first box car trip). Since Harris was critical to the formation of the group, so the Algoma experience was critical to Harris. Time spent together with MacCallum, MacDonald, Lismer, Jackson and Johnston generated a nexus of ideas. Of the box car trips, Jackson writes: “There were lively interchanges of opinion. There was the stimulus of comparison and frank discussions on aims and ideals and technical problems which resulted in various experiments...” He continues: “In the boxcar with the stove to keep us warm, the discussions and arguments resumed on Whitman, Mary Baker Eddy, Madame Blavatsky, Cezanne and Van Gogh until late in the night.”

Thus, despite Harris’s apparent struggles with the terrain, he seems most assuredly to have benefitted from the camaraderie of trips and eventually understood the region well enough to produce masterful work, whether or not it was ultimately his preferred locale. While this work does not depict the lush, dense and chromatic vegetation, rocky outcrops or lakes of, say, Batchewana, it does serve a higher purpose beyond the anecdotal. Here the water tower captured on the second box car trip (ca.1919) stands like a sentinel, foreshadowing other lone and imposing motifs Harris would favour in the coming years: the lighthouse at Father Point (ca. 1920), an old stump (ca. 1926), an isolated peak in the Rockies (ca. 1930), a Davis Strait iceberg (1930), a floating triangle (ca. 1937). In this painting we have a hint to the direction in which Harris is headed and which perhaps, at this time, he himself was still unaware of. Like Blaise Pascal, who famously wrote: ”If I had more time I would have written a shorter letter”, Harris ultimately sought increasingly to render the essence of the idea. Knowing what we know about how this story ends, Watertower strikes us as unusually prescient.