“Best known for his abstract paintings, Canadian artist Jack Bush can be counted among the master colourists of the 20th century.”

Art historian and curator Dr. Sarah Stanners has devoted herself to compiling the artist’s catalogue raisonné, a project that will thoroughly document more than 1,600 paintings, including full information on provenance, exhibitions, bibliography, and excerpts from the artist’s own diary.

The final call for submissions to the catalogue raisonné is December 31, 2020.

The anticipated release of the publication in 2021 will reflect a decade’s worth of research on the part of Dr. Stanners, and will provide a comprehensive and definitive survey of the paintings of one of Canada’s first internationally-recognized artists.

To mark the occasion, Dara Vandor sat down with Dr. Stanners to ask her about the construction of an artist’s catalogue raisonné, the furthest places she has travelled to track down Bush paintings, and of course, her favourite work by the artist.

How did you end up in the arts and in this current role? I am always fascinated by people’s paths to their calling, and if their career was a straight shot towards a goal, or more of a meander.

I am one of those annoying people who knew what they wanted to be from an early age. I took an art history course in high school and it felt right. But my interest may have sparked even earlier, since my Mom is an artist. We had art books lying around all the time, which I explored from an early age, even if only through images. I have clear memories, from about the age of four, of being fascinated with the size of Picasso’s eyes.

How did you find your way to Jack Bush and your role tending to his legacy?

A chapter in my Ph.D. dissertation was focused on Jack Bush. In the process of writing this chapter, I wanted to see more works by the artist – and certainly more than I could see on display at a museum without a special exhibition – so I made a point of meeting people who collected the artist’s work. I was introduced to Jack Bush’s former art dealer, David Mirvish, who then introduced me to a Boston-based collector of Color Field art, Lewis Cabot. From their mutual encouragement and support, the seeds for the catalogue raisonné were planted. Under the auspices of the Estate of Jack Bush and the David Mirvish Gallery, and in affliation with the University of Toronto, where I house the project fund to manage private donations, the artist’s legacy is furthered and the catalogue raisonné is made possible. I am fortunate to be in this position.

Can you tell us a little bit about Jack Bush and what makes his work so special?

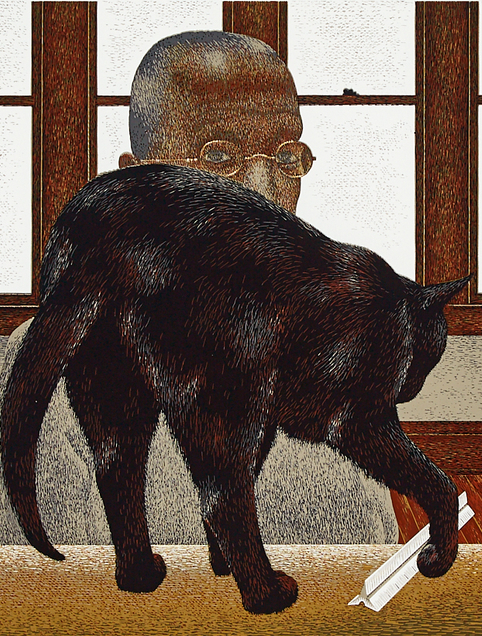

Jack Bush’s fifty-year long career as a painter developed as a beautiful arc from landscape to abstraction. How he made the leap is deeply fascinating. In 1947, Bush began to see a psychiatrist for issues relating to tension. His psychiartrist, Dr. J. Allan Walters, advised him to begin painting without any preconceived idea, to just let the colours and forms flow. So Bush’s abstract art was born from therapy, in the very beginning.

Could you explain the importance of a catalogue raisonné? How are they constructed?

A catalogue raisonné is one of the most traditional forms of art writing, which you don’t often see since the process is both extremely time consuming and expensive. By definition, a catalogue raisonné thoroughly catalogues the full body of work of an artist. Sometimes a catalogue raisonné focuses on a particular medium. I am compiling the catalogue raisonné of paintings by Jack Bush, which will be a comprehensive record of the artist’s painted works. Compiling a “CR” involves accounting for all inscriptions, bibliography, exhibition history and the provenance of each and every painting. Ideally, the painting will be illustrated with a high quality photo and the current location, if known.

Tell us what is involved in maintaining an artist’s catalogue raisonné. How do things get added (or perhaps even subtracted)?

When a painting is submitted (an official submission form is found on the project website at www.jackbush.org) I first check to see if the painting appears in any of the artist’s own handwritten records. Perhaps most importantly, there should be clear records of provenance. Jack Bush had strong commitments with a short list of art dealers, whose records may shed light on a painting’s provenance. Archives, the Estate of the artist, or a collector’s receipt of sale might also help to determine the provenance of a painting. Records of exhibition are also helpful, especially during the artist’s lifetime. I work closely with the Estate of the artist; Jack Bush’s three sons represent the Estate and Terry Bush acts as its head. We discuss any questionable issues of attribution, if need be. Research is key, and it is also of paramount importance to examine a painting in person.

In my position as an expert on the artist, there is an element of connoisseurship involved – sometimes a painting is submitted which is not at all in keeping with the artist’s methods or style around the date of execution. I have more than a 1,100 photos of versos (the backs of paintings). Jack Bush was an habitual artist and when I see, for example, the wrong materials or methods of preparation of the painting, I have reason to be concerned. All of these safeguards – along with the artist’s own archive, including inventories and his daily diary – make the process of inclusion in the catalogue raisonné strict; I have therefore not had a case of ‘subtracting’ a work from the record. ‘Substracting’ a painting implies that it was already included in the catalogue raisonné, but no painting is added without scrutiny.

Excluding a painting is another story. There have been cases of misattributions (Bush is a popular name) and cases of fakes, which are certainly excluded from the catalogue raisonné. Some paintings require further study; that is, their may be no clear evidence of authenticity but there may also be no reason to say it is not a Jack Bush painting. While the art market wants a black or white answer – is it real or is it not? – art historians are comfortable with grey areas, which may simply require more research, time to study the work closely, or even science to establish its authenticity.

How do you track down all of these works? Where do you even start once you have exhausted institutional sources? I am assuming that so much of what Bush made was sold pre-internet, and much of it to private collectors, though I have heard you mention that Bush himself was a meticulous record-keeper.*

I am, in fact, super happy that the sales history is largely pre-internet. I am able to follow paper trails! It is rare, however, to find personal names attached to paintings published online. There are a couple of blank spots in dealer sales records from the 1990s because files failed to save or the technology did not survive the evolution from floppy disk to online, for example. There are benefits to analogue records. Jack Bush produced hand-written records of his paintings. He also kept a daily diary for 25 years. The Estate of Jack Bush continued to keep records of the whereabouts and sales of paintings after the aritst’s death in 1977. I also research the records of art dealers. If dealer records are not found in a public archive, it requires that I forge trusting relationships with current dealers, or their descendents.

Sometimes I find paintings in unexpected ways, such as a real estate feature in the newspaper – and there it is – a big Bush painting in the living room! Other times I will begin with a lead, such as previous research done by Karen Wilkin, for example, but since that research was done in the past the owner of the painting may have passed away. In such cases, I comb through obituaries and find next of kin. Most of all, word of mouth has been the best method. Show this article to a friend, and maybe their aunt has a painting!

How long has it taken you to put this together?

I have been working on the Jack Bush catalogue raisonné since 2011, but I began my research on the artist during my graduate studies, so that would be around 2004.

I am sure it is difficult to choose, but if you absolutely had to—what is your favourite work by Jack Bush?

Well, my favourite period of work by Jack Bush is the early 1960s. If forced to pick a favourite, it might be St. Ives, which is a 1962 Flag painting in the collection of the Kitchener-Waterloo Art Gallery. The blue is so deep and the composition is intruiging. It stands out in my mind.

How has your work changed with the advent of COVID-19? Do you think it will return to the way things were or has the pandemic entirely shifted the way you work?

While I wish the pandemic had never happened at all, I am glad that it happened now and not at the beginning of the project; in that case, the halt on travel may have derailed the whole thing. I am now primarily focused on preparing the manuscript for publishing, so I am no longer traveling a solid week or more out of every month. I was hopping around a lot of airports, car rentals, and museums for the first six years or so. I actually just finished up the last of my in-depth archival research trips at The Getty Institute in Los Angeles last August and I remember thinking, what a fantastic place to wrap up my core research (I was looking at the papers of Clement Greenberg).

But I would like people to know that while museums are opening, even if limited, this often does not include their libraries. In-person research to the valuable archives in our institutions has been negatively effected by the pandemic. Again, I feel fortunate that I am nearing a natural end to the project at a time when I may have been forced to slow down anyway. As planned, I am now making a ‘last call’ for paintings; the deadline to submit paintings to the catalogue raisonné is December 31, 2020.

What does a typical day look like for you?

I am focused on preparing the manuscript now. I do a heck of a lot of writing and fact checking – making sure that bibliographic references are correct, collecting up to date acknowledgement lines from collectors and institutions, reviewing exhibition lists, and writing short catalogue entry notes or essays. Some days I am chasing images – contacting auction houses to request an image, or arranging a licencing agreement with a museum.

What is the furthest or wildest place that you have gone or person you had to track down in order to see a Bush painting or fill in a piece of the Bush puzzle?

One ‘off the beaten track’ location was in Glenfield, England, in the collection of the Leicestershire County Council. Another far-flung location is in Bermuda at the Masterworks Museum. His paintings are all over the U.S., too, from Pasadena (where he has relatives) to Cape Cod, including a home with its own lighthouse! Private collections offer the best surprises. I’ve seen Bushes hang next to Bonnard, de Kooning, Matisse, Thomas Hart Benton, and even a Velázquez.

Can you share a favourite anecdote about Bush?

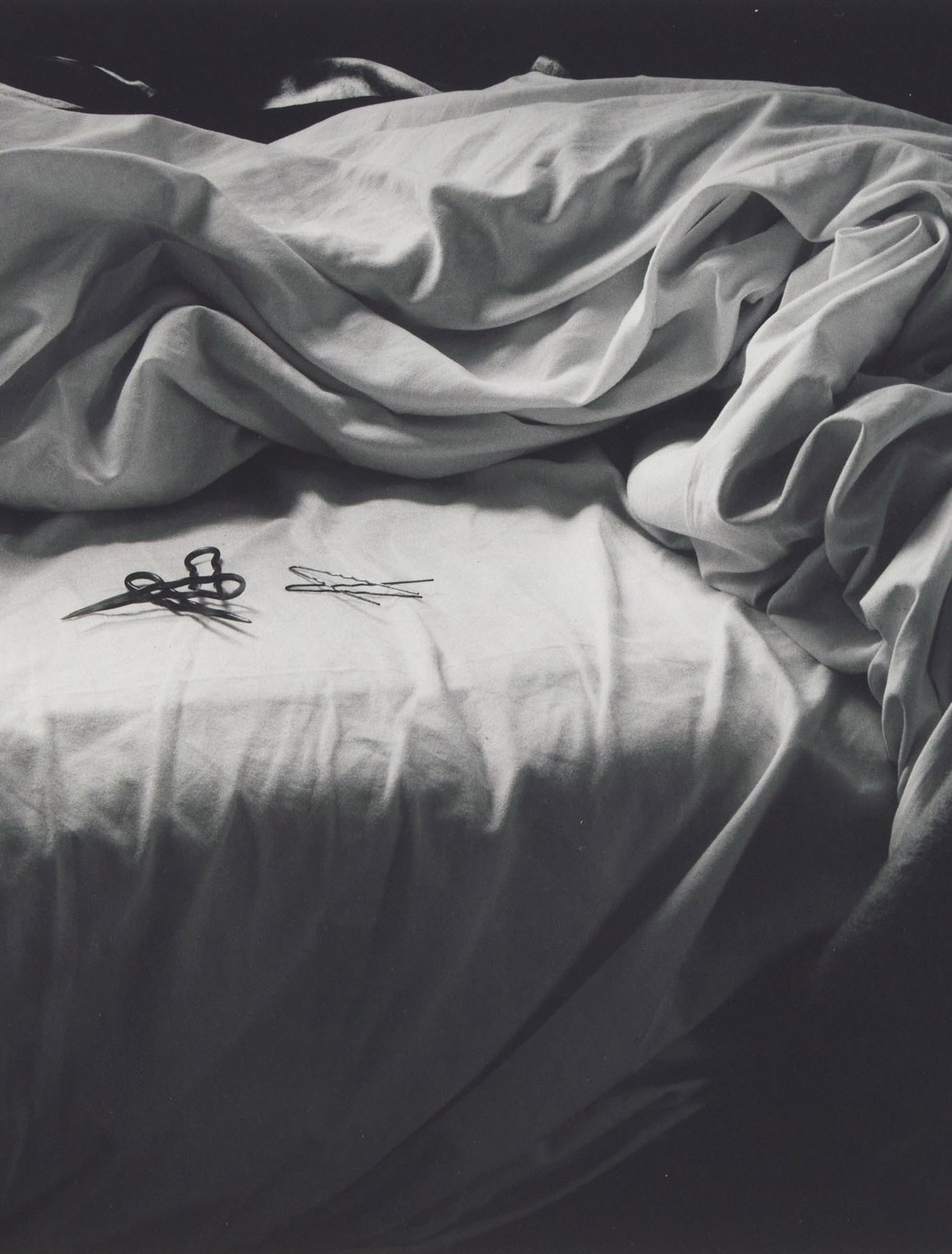

Around 1974, the renowned photographer Yosuf Karsh went to Jack Bush’s studio to take a portrait of the artist. Apparently Karsh was confused, and asked, “where’s your easel?” I suppose he planned on finding a traditional painter, and the resulting photo feels awkward, as if Karsh couldn’t connect to Bush’s manner of painting. At that time, Bush often used sponges to paint and he would simply tack up a piece of unstretched canvas to a false wall, rather than use any apparatus such as an easel.

Was there a discovery that you are particularly proud of?

Reuniting a painting with its original title is always a thrill. Sometimes a painting comes up at auction as “Untitled” but Bush always gave titles to his paintings. On a research level, finding the inventory of paintings that reflected what remained in the artist’s studio the day after his death was important. I found this list in the Greenberg papers.

While Bush’s work probably composes the majority of the art that you look at, can you tell us a few other artists whose work you admire?

I have published articles and book chapters on the work of Henry Moore and, more recently, a peer reviewed article on Anthony Caro. Modern British art has always captured my attention. Painters such as Patrick Heron, William Scott and John Hoyland were great colourists.

What are you currently working on and/or what will you be working on in the coming months/years?

I am currently working on a short essay to contextualize the work of 1952 for the Jack Bush catalogue raisonné. In order to bring the catalogue raisonné to fruition, I don’t have time to work on much else. In the future, I want to remain dedicated to the kind of research that presents an artist’s work in depth. Monographic studies are not currently fashionable, but if we are only ever spinning theory or theme-based exhibition catalogues, we might not get the full picture.

Thank you so much for taking the time to speak with us, Dr. Stanners. We will be following your project closely!

For those wishing to submit to Bush’s catalogue raisonné, please visit: JACK BUSH PAINTINGS, A CATALOGUE RAISONNÉ.

Waddington’s is honoured to have offered numerous exceptional works by Jack Bush, including most recently, two pieces sold in our September 2020 Canadian Fine Art auction, “Jeté en l’Air” and “Valley in Winter (Hogg’s Hollow).”

To view all work by Bush sold by Waddington’s, please click here.