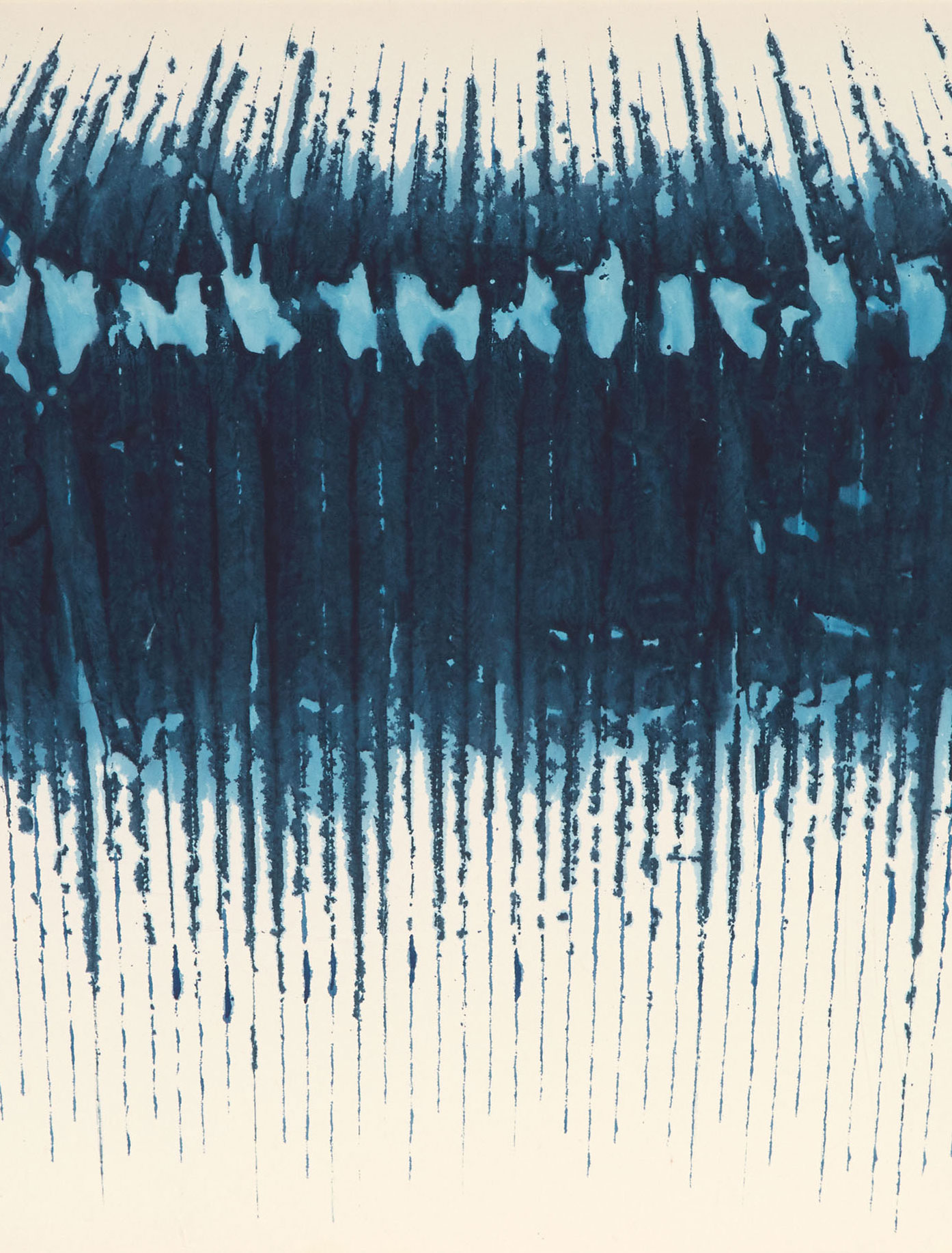

Karel Appel’s works are widely considered to embody the spirit of post-war European art; characterised by bold use of colour, expressive brushwork and a style inspired by folk art, outsider art, and children’s drawings.

His involvement with CoBrA, an avant-garde movement he founded in 1948 along with Asger Jorn, Constant and Corneille, brought attention to the young artist’s work in both Europe and North America. CoBrA, an acronym for the cities the founding artists were from (Copenhagen, Brussels, and Amsterdam), was centred around a rejection of geometric abstraction and rationalism, which CoBrA artists identified with de Stijl. De Stijl was the dominant aesthetic of Dutch art at the time, best typified by the work of Piet Mondrian. CoBrA artists also rejected the similar hegemony of French Surrealism, another major style of the period.

Their aim was to paint the human psyche in all of its disorder and primitivity, reflecting the trauma and unease of the post-war period. Brushwork was often frenetic, the colours vibrant, taking inspiration from the creativity and energy of children. Margalit Fox sums up Appel’s style accordingly: “Some critics discerned violence or even madness in Mr. Appel’s work, with its liberal use of red and its semi-figurative images of grotesque limbs and distorted, grimacing faces. But to other viewers, the unrestrained masses of paint, which Mr. Appel sometimes squeezed onto the canvas straight from the tube, embodied the life force itself.”(1)

Helen A. Harrison, writing in the New York Times in 1981, explained that CoBrA’s major achievement “was in fostering an amalgam of aspects of the major trends in contemporary artistic thinking” with “the dark, mystical Northern sensibility that gives their work its peculiar character, so appropriate to postwar Europe.” She added: “In short, they seem to have been able to express both optimism and anxiety at the same time.” (2)

Though CoBrA disbanded in 1951, its spontaneous and colourful aesthetic has been credited with reinvigorating Dutch modern art and inspiring subsequent generations of artists. The playful spirit it promoted has also characterised Appel’s subsequent career, emblematized by thick impasto, energetic spontaneity, saturated colour and human or animal subjects. Appel recalls how formative the group was for him: “The CoBrA group started new, and first of all we threw away all these things we had known and started afresh, like a child — fresh and new. Sometimes my works look very childish, or childlike, schizophrenic or stupid, you know. But that was the good thing for me. Because, for me, the material is the paint itself. The paint expresses itself. In the mass of paint, I find my imagination and go on to paint it.” (3)

Appel began dividing his time between Europe and New York City beginning in 1957. There he would connect with Abstract Expressionist painters including Willem de Kooning, whose dramatic use of paint would influence Appel’s style. In New York, Appel’s art became even freer, though like his earlier work, continued to walk a tightrope between abstraction and figuration, never entirely one or the other. Appel also met jazz musicians Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis and Count Basie, whose free-flowing styles would also impact his painting.

The 1960s marked a period of decline and tragedy for Appel, when painting went out of fashion and his second wife, Machteld, passed away. But Appel and his irrepressible style could not be kept down long – Appel remarried his third and last wife, began working again, and signed on with art dealer Annina Nosei, who also represented Jean-Michel Basquiat. Appel would find fresh inspiration in the flattened aesthetics of Pop Art, which he reinterpreted using his signature style.

Appel continued to experiment until the very end of his life. He worked with various media, including sculpture, textile, ceramics, and printmaking, all which he imbued with his signature primal energy. Franz W. Kaiser, writing for the Appel Foundation, notes that “Appel early on recognizes that sticking to one’s own comfort zone inevitably leads to formalism and repetition. He consciously exposes himself again and again to the unknown. This can be a new material or a new method, but also the style of a current avant-garde, of which he takes up individual aspects and integrates them within his characteristic way of working.” (4)

About the auction

Held online from May 24-29, 2024, our spring auction of Canadian and International Fine Art brings together exceptional work from around the world. This auction features celebrated Canadian artists such as Cornelius Krieghoff, A.Y. Jackson, P.C. Sheppard, A.J. Casson, Bertram Booker, Alexandra Luke, Jean Paul Lemieux and Yves Gaucher as well as important First Nations artists Norval Morrisseau, Roy Thomas and Alex Janvier. International highlights include work by Jules Olitski, Karel Appel, Kwon Young-Woo, Norman Bluhm, Józef Bakoś, Léon Lhermitte and Montague Dawson.

Previews will be available at our Toronto gallery, located at 275 King Street East, Second Floor, Toronto:

Thursday, May 23 from 10:00 am to 5:00 pm

Friday, May 24 from 10:00 am to 5:00 pm

Saturday, May 25 from 12:00 pm to 4:00 pm

Sunday, May 26 from 12:00 pm to 4:00 pm

Monday, May 27 from 10:00 am to 5:00 pm

Tuesday, May 28 from 10:00 am to 5:00 pm

Or by appointment.

Please contact us to find out more.

- Margalit Fox. “Karel Appel, Dutch Expressionist Painter, Dies at 85.” The New York Times, May 9, 2006. Accessed April 2, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2006/05/09/arts/design/karel-appel-dutch-expressionist-painter-dies-at-85.html

- Helen A. Harrison. “Art; Unfolding the Esthetics of the Cobra Group.” The New York Times, May 10, 1981. Accessed April 2, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/1981/05/10/nyregion/art-unfolding-the-esthetics-of-the-cobra-group.html, cited in Margalit Fox, ibid.

- Fox, ibid.

- Franz W Kaiser. “Biography.” Karel Appel Foundation. Accessed April 2, 2024. https://karelappelfoundation.com/karel-appel/chronology

Related News

Meet the Specialists

Goulven Le Morvan

Director, International Art, Montreal

Alicia Bojkov

Consignment Specialist, International Art