a backgrounder on the stone used in Inuit Stone sculpture

If you’re curious about the distinctive differences in Inuit stone sculpture – including those featured in our upcoming Discover Inuit Art Auction – we think you’ll enjoy this primer.

Did you know the period and location that an Inuit stone sculpture was created can be determined based solely on the type of stone used?

Even in the absence of a signature, it’s possible to triangulate the stone’s origin based on the unique geology of the Arctic, as the type of stone can vary greatly from one community to the next. Inuit artists typically use materials that can be found locally, and regions can be distinguished by their distinctive rock or rocks, sometimes even down to a particular quarry or vein. Once a particular vein of rock has been exhausted, another must be found, meaning that particular shades and variations of rock truly encapsulate a time and place. For example, in Kimmirut (Lake Harbour), some of the most desirable carving stone used during the 1970s and 80s could only be gathered at low tide. The stone found in this location often slowly changes colour from light green to shades of rusty red as the iron in the stone slowly oxidized after being exposed to the air.

How the Type of stone influences the sculpture

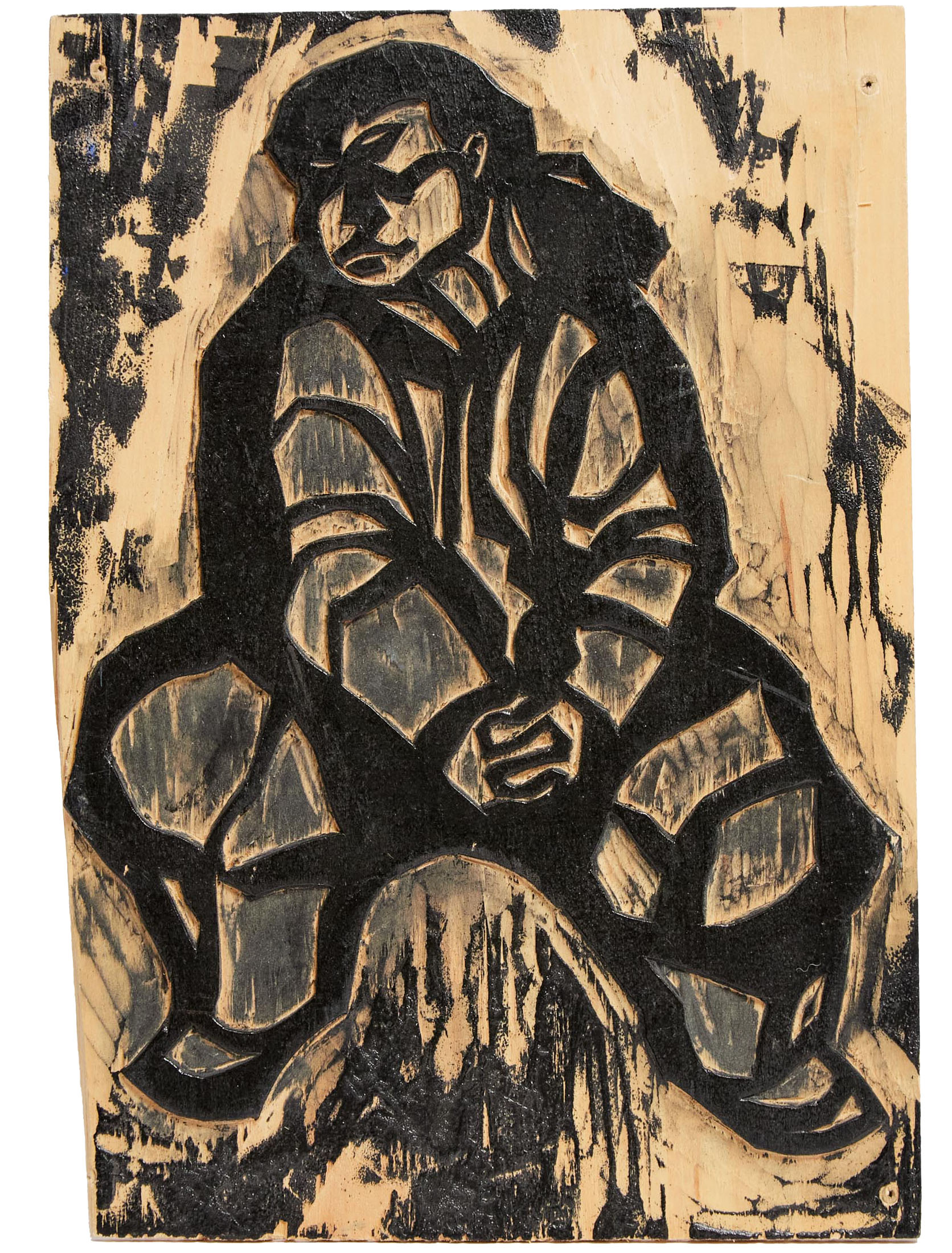

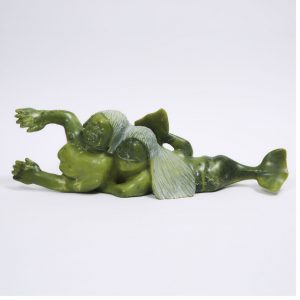

While steatite, also known as soapstone, is the stone most commonly associated with the Arctic, harder materials such as serpentine, chrysotile, olivine, chlorite, peridotite, granite and even quartz are used as well. The characteristics of a particular region’s stone have had a direct impact on the sculptural style of that area. As an example, the hard, brittle grey stone used in settlements such as Arviat (Eskimo Point) and Kangiqliniq (Rankin Inlet) lends itself to minimal but powerful depictions with little piercing or detailing. In contrast, the rich green stone of Kinngait (Cape Dorset) is strong enough to allow aggressive piercing and undercutting, but soft enough to embellish with fine detail and then finish with a high polish.

The stone itself will dictate how refined and elaborate the sculpture can be. Acclaimed artist Oviloo Tunnillie explained that “it can be very difficult to sculpt the idea that you have in your mind. If your idea doesn’t match the shape of the stone your idea may have to change because you have to accept what is available in the rock.” She noted that she would not begin a work until she was certain about how she would approach each unique stone block.

Serpentine

One of the most common types of stone used, serpentine, is often marked by inclusions—and inclusion referring to any material that is trapped inside a mineral during its formation. The inclusions in serpentine give it its unique colour variations. This type of rock is commonly found in Nunavut, especially in Kinngait (Cape Dorset) where it is abundant, and throughout the Arctic

Serpentine is a semi-soft metamorphic rock, which allows carvers to create more complex compositions with a higher degree of detail if they so choose. It can be polished to a high shine and lustre. Serpentine is often thought of as being green, but it can be found in brown, dark olive and even black shades.

Notable artists working in serpentine: Osuitok Ipeelee, Sheoqjuk Oqutaq, Nuyaliaq Qimirpik.

Steatite

Steatite can be found throughout the Arctic and around the world, used by diverse groups including the ancient cultures of Egypt, China and India. This metamorphic stone has been used by the Inuit for thousands of years, particularly for use in carved qulliqs. Qulliqs are the traditional oil lamps that served as the only source of heat and light during long winters—the single most important item in an Inuit dwelling.

Softer than serpentine, steatite is commonly known as soapstone. It is worth noting that “soapstone” is often used erroneously as an umbrella term to denote any Inuit carving, though it actually refers to a particular type of stone. Steatite is found in the Arctic in blue-gray, gray and white hues, though modern carvers have begun to import more diverse shades of this rock from around the world. Steatite is harder to polish to a high shine than serpentine, and some artists find it too soft to work with. It is known for having a “greasy” feel to it—hence the soapy nickname. However, this softness allows carvers to achieve a higher level of details than with other stones.

Notable artists working in steatite: Bill Nasogaluak, Jonasie Faber, Abraham Anghik, David Ruben.

Argillite

Though found throughout Canada, this sedimentary rock is commonly associated with Nunavik and Kimmirut (Belcher Islands) carvers.

Argillite is formed from a mixture of clay and other minerals, resulting in an extremely finely-grained stone able to take a great level of detailed carving. Commonly found in dark grey shades, other colours are known. An interesting feature of this stone is how, when filed or etched, it turns white. These markings are retained, allowing artists to inscribe images or texture on the surface of the stone. Argillite, like serpentine, can be polished to a high shine

Notable artists working in argillite: Davidialuk Alasua Amittu, Joe Talirunili, Mark Ilisituk.

BasalT

A hard and heavy igneous rock, this gray or black stone is known as being difficult to work with and hard on the artist’s tools.

Because of these qualities, basalt carvings are often minimalist, more suggestive than literal. Shape and volume are used to great effect.

Notable artists working in basalt: Lucy Tasseor Tutsweetok, Barnabus Arnasuungaaq, Tuna Iquliq.

FIND OUT MORE ABOUT Inuit Art AUCTIONs AT WADDINGTON’S

We are currently accepting consignments, and invite you to browse our upcoming auctions.

Please do not hesitate to contact us for with any questions, including requests for additional images, information or detailed condition reports.

Explore Katilvik

We also invite you to explore Katilvik, our virtual resource centre for those passionate about Inuit art and stone sculpture.

Suggested reading

The Art of Stone: Quarry, From Quarry to Co-op, by John Geoghegan, Jan 22, 2020, Inuit Art Quarterly.

Related News

Meet the Specialists

Palmer Jarvis

Senior Specialist

Duncan McLean

President, Senior Specialist