The 1960s were an important decade in the evolution of Inuit art. Below, we highlight six works from the period, all of which are included in our major auction of Inuit & First Nations Art, held online from May 24-29, 2024.

Davidee Mannumi ᒪᓄᒥ (1919-1979), Kinngait (Cape Dorset) / Iqaluit (Frobisher Bay), TRANSFORMING SPIRIT, CA. 1961

This remarkable and apparently unique transformation sculpture from Iqaluit (Frobisher Bay) dating to the early 1960s is documented both in George Swinton’s original 1972 publication Sculpture of the Eskimo, and again in the revised 1994 iteration of the text. Attributed first to the artist Munamee of Iqaluit, and later specifically to Davidee Mannumi. Although Davidee Mannumi resided in both Kinngait (Cape Dorset) and Iqaluit, the work is a significant departure from the artist’s known oeuvre. (3)

Swinton had an eye for images of sinuous and startlingly otherworldly strangeness, and favoured the output of artists such as Eli Sallualu Qinuajua. (4) In both the 1972 and 1994 editions of his seminal book, he featured the present work alongside Kiugak (Kiawak) Ashoona’s iconic Howling Transforming Spirit. It is not difficult to see why. Mannumi’s voluminous Transforming Spirit is a decidedly languid – if menacing – counterpoint to the gnashing teeth and hard edges of Kiawak’s 1963 creation.

The brooding figure’s broad high shoulders, elongated transforming face, and forward leaning torso are expertly balanced on a single foot. Uniquely, the creature’s back exudes tendrils of hair conjoined with a disembodied humanoid head.

Kenojuak Ashevak ᑭᓄᐊᔪᐊ ᐊᓯᕙ, CC, RCA (1927-2013) / Johnniebo Ashevak ᔭᓂᕗ ᐊᓴᕙ (1923-1972), Kinngait (Cape Dorset), TWO BIRDS, CA. 1965

Beginning in the mid 1950s, before taking up drawing Kenojuak Ashevak and her first husband Johnniebo expressed their visions in stone. Kenojuak continued carving a modest number of sculptures until the end of her long career, and Johnniebo carved until his death in 1972. Attribution of sculptures by the pair can be difficult as both are documented as having signed some of each other’s artworks, and possibly collaborated on others. (5)

The present sculptures date ca. 1960 and are among the couple’s earlier examples. Confidently sculpted and finely finished, they exhibit less exaggerated, more life-like proportions than many of Kenouak’s or Johnniebo’s later investigations of avian subjects.

In the 1990s images of the two sculptures were shown in Kinngait (Cape Dorset) to artist and studio manager of the West Baffin Eskimo Cooperative, Jimmy Manning. When Manning was asked who they were made by, he scoffed at the apparent naivety of the enquiry, answering that they were the work of Kenojuak. (6)

Francis Kaluraq ᑲᓗᕋ (1931-1990), Qamani’tuaq (Baker Lake), FIGURE WITH FOUR FACES, CA. 1965

Relatively little information is readily available about the important early Qamani’tuaq (Baker Lake) artist Francis Kaluraq. His early works in sculptures are impressive in their distinctly recognisable and monumental style. George Swinton evidently appreciated Kaluraq’s work and included sculpture by the artist both in Eskimo Sculpture in 1965, and in his 1972, and revised 1992 editions of Sculpture of the Eskimo. (7)

Although active as a printer in the 1970s in Qamani’tuaq, very few sculptures by Kaluraq have come to market. The present work, Figure with Four Faces, likely dating to the mid-1960s, appears to be the only example of the four-faced subject in the artist’s apparently small oeuvre. In some regards stylistically evocative of the formalised style of fellow Qamani’tuaq artist George Tataniq, Figure with Four Faces predates Tataniq’s best known sculptural statements of the early 1970s. With its subtle abstraction, confidence of line, and enigmatic subject matter, it stands favourably against the important later works of Qamani’tuaq figuration.

6.5 x 5 x 3.5 in — 16.5 x 12.7 x 8.9 cm. Estimate $8,000-$12,000

John Pangnark ᔭᓐ ᐸᓇ (1920-1980), Arviat (Eskimo Point), FIGURE, CA. 1968

The first documented sculptures by John Pangnark, while abstract, have readily identifiable anatomical elements, a characteristic that would recede in later works, subsumed by an increasing degree of abstraction and confidence in line and volume. The present sculpture made ca. 1968 is an uncommon example of his earlier period and shows a more developed figuration.

The two arms of the figure are readily identifiable, and stretch outward from the figure. The face is a whisper of finely-etched lines, and as elsewhere in Pangnark’s sculptures, the apparently closed eyes and mouth seem to betray a calm, delicate smile.

The present sculpture, exhibited in Inuit Art from the Canadian Arctic, at the Bayly Art Museum at the University of Virginia in 1994, is available for the first time since it was sold at Snow Goose Gallery in Ottawa, to the previous owner in 1974.

Davidialuk Alasua Amittu ᑎᕕᑎᐊᓗ (1910-1976), Puvirnituq (Povungnituk), LEGEND OF THE HUNTER AND MERMAID, CA. 1960

For many, Davidialuk Alasua Amittu is the preeminent Inuit storyteller in image and word. The fatal and the tragic, the mythical and the commonplace are recorded in his iconic images. The present sculpture tells the story of the hunter and the mermaid.

Speaking of the subject in the 1977 Marybelle Myers publication Davidialuk ᑎᕕᑎᐊᓗ 1977, the artist tells the story of a poor hunter who encounters a stranded woman who is half human and half fish. The hunter saves her by levering her back into the water and in return is gifted a record player, rifle, and sewing machine. Davidialuk cites this first gift as the origin of these mechanical contrivances. (1)

Pinnie Nuktialuk ᐱᓂ (1930-1969), Inukjuak (Port Harrison), WOMAN MENDING KAMIK AND MAN FLENSING SEAL, CA. 1960

Little information is readily available about the talented early Inukjuak (Port Harrison) artist Pinnie Nuktialuk. Works by Pinnie show many of the finer aspects which characterise works of her Inukjuak contemporaries such as Eli Weetaluktuk, and perhaps most notably Johnny Inukpuk, the latter of whose camp she was a member. (2)

The confidence and consistency of style in these two sculptures, Woman Mending Kamik and Man Flensing Seal speak to her talents, as do the restrained flashes on fine detail found in the tassel of the man’s hat and the braids of the woman’s hair. The two sculptures, no doubt conceived as a pair, have in all likelihood been together since the time of their manufacture. Similar in scale and bearing near identical inscriptions, they might easily be titled Division of Labour, giving equal weight, as they do, to the separate, but mutually necessary tasks that have so often been divided between partners.

ABOUT THE AUCTION

Held online from May 24-29, 2024, Waddington’s is pleased to present our major spring auction of exceptional Inuit & First Nations Art. Important artworks this season include works of sculpture and graphics by Karoo Ashevak, Jessie Oonark, Kiakshuk, John Pangnark, Pauta Saila, Aisa Qupirualu Alasua, Parr, Osuitok Ipeelee, Kiugak Ashoona, Joe Talirunili, John Kavik, Kenojuak Ashevak, Johnny Inukpuk, Thomas Ugjuk, Ennutsiak, Davidialuk Alasua Amittu, Beau Dick, Charlie James, David Ruben Piqtoukun, Abraham Apakark Anghik, Manasie Akpaliapik, Judas Ullulaq, Barnabus Arnasungaaq, and John Tiktak.

Previews will be available at our Toronto gallery, located at 275 King Street East, Second Floor, Toronto:

Thursday, May 23 from 10 am to 5 pm

Friday, May 24 from 10 am to 5 pm

Saturday, May 25 from 12 pm to 4 pm

Sunday, May 26 from 12 pm to 4 pm

Monday, May 27 from 10 am to 5 pm

Tuesday, May 28 from 10 am to 5 pm

Or by appointment.

Please contact us for more information.

(1) Marybelle Myers, Davidialuk ᑎᕕᑎᐊᓗ 1977 (Montreal: Fédération des coopératives du Nouveau-Québec, 1977), unpaginated.

(2) Darlene Coward Wight, Early Masters: Inuit Sculpture 1949-1955 (Winnipeg: Winnipeg Art Gallery, 2006), 83.

(3) Houston, James. “Davidee Mannumi.” The Canadian Encyclopedia. January 30, 2008. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/davidee-mannumi

(4) Personal correspondence with Harold Seidelman, author and colleague of George Swinton.

(5) Richard C. Crandall, Inuit Art A History (North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2000), 142.

(6) Jimmy Manning, personal communication with the author, ca. 1999.

(7) George Swinton, Eskimo Sculpture (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart Ltd., 1965), 93, 100; George Swinton, Sculpture of the Eskimo (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart Ltd., 1972/1992), 222, pl. 684, 226, pl. 711.

Related News

Meet the Specialists

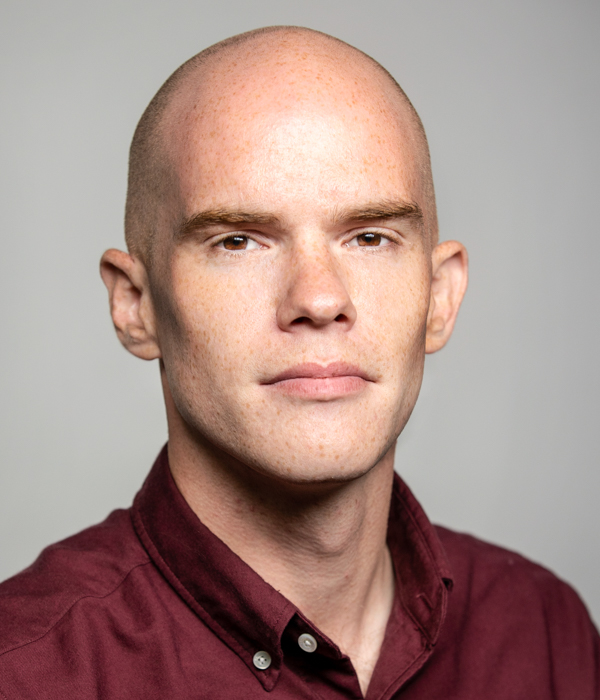

Palmer Jarvis

Senior Specialist

Elizabeth Gagnon

Consignment Coordinator