To believe in transformation is to be human. Cross-cultural and deeply encoded in our psyche, aspirations of transformation, and the perception of its role in the lives of those around us underpins the sweep of history, our religions, and most definitely our collective behaviours. For what else does a New Year’s Resolution have in common with the most sacred of ceremonies? It is the belief that we can become that which we are not, that the micro or macrocosmic can be changed through word and deed, that we are connected to something powerful and yet accessible.

Notions of transformation have long figured prominently in the worldview of circumpolar peoples. Images depicting the phenomenon in art and material culture have reoccurred throughout the history of the Inuit, at times fading out of common use, only to reemerge as a defining element in other periods. [1] In the twentieth century, representations of transformation have typically been depicted as a metamorphosis between human and animal states or between two animal species. Inuit oral traditions suggest that in times past, animals and humans spoke the same language, and could even intermarry.[2] While this interwoven proximity is confined to history, many continue to believe that transformation between species is possible, most notably in times of deprivation and need. Animal spirits remain close to the Inuit, particularly to the community’s shamans. Shamans are often thought to possess the ability to channel and communicate with various entities, benefiting from their guidance and protection, while in turn reaffirming the proximity of worlds ethereal and material.

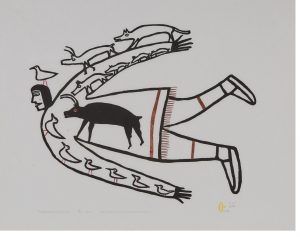

In the twentieth century shaman’s spirits have often been depicted as familiars accompanying those with who they commune. In the case of lot 25, Jessie Oonark’s The Flight of the Shaman, the shaman’s attendant spirits are depicted guiding a journeying figure from both inside and outside of its body. In The Coming and Going of the Shaman: Eskimo Shamanism and Art, author and curator Jean Blodgett poignantly describes the powers of the Inuk shaman to take flight as follows:

“Shamans could fly to the moon, to the sun, to the heavens, and to the underworld. They visited deities above the earth and below the sea. They flew or descended to the bottom of lakes and to the lands of the dead, both in the sky and underground. They might fly through space or around the earth. They were transported by spirit helpers and benign deities. They also traveled from one earthly locale to another; from Canada to Point Barrow, from the Diomede Islands to St. Lawrence Islands, or even from Alaska to San Francisco and back.”[3]

Encoded in their essential cosmology, transformation, spirit helpers, and flight are deeply intertwined in Inuit culture, and continue to inform Inuit art. Themes of transformation remain common in the art of younger generations, with contemporary artists employing long established imagery and methodology to express contemporary perspectives, such as in the work of Bill Nasogaluak, evident in lots 2 and 4, where the artist has created unflinching images of climate change, and the harmful intergenerational effects of alcohol.

ABOUT THE AUCTION

Waddington’s invites you to browse the full gallery for this concise, powerful auction, online from March 12-17.

Drawing on mythology, tradition, and an evolving relationship between the land and its inhabitants, artists Bill Nasogaluak, Nick Sikkuark, Josiah Nuilaalik, David Ruben Piqtoukun, Abraham Apakark Anghik, Floyd Kuptana, and their contemporaries offer us images of transformation and change. Artworks in sculpture and graphics explore themes as diverse as the shaman, climate change, depression, and the impacts of industry in the North.

Please contact us to arrange a preview appointment, or for more information, additional photographs and condition reports.

[1] Blodgett, Jean, The Coming and Going of the Shaman: Eskimo Shamanism and Art, Winnipeg: The Winnipeg Gallery of Art, p. 75

[2] ibid, p. 91.

[3] ibid, p. 111

Related News

Meet the Specialists

Palmer Jarvis

Senior Specialist

Elizabeth Gagnon

Consignment Coordinator

Duncan McLean

President, Senior Specialist