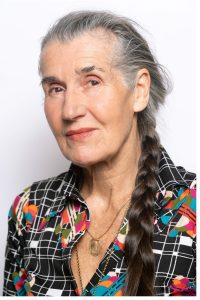

When Natalka Husar arrives at Waddington’s to be interviewed, I find myself having to prise her away from my colleagues, all of whom seem to have been drawn out of their offices and into her orbit, as if by some unseen law of physics. She speaks with them on a wide range of topics, and I find myself itching to turn on my recording device, to thrust it into these informal conversations so as not to miss anything.

Husar is the rare example of an artist who is able to see herself and her work with equal clarity. Though she has decades of experience within the art world—a milieu overly fond of obfuscation and specialized jargon—she speaks plainly, more interested in connection than clout. Perhaps this lucidity comes from the very nature of her work, which has always been unflinching, equal parts brassy and intimate. While it is far too easy to conflate art with artist, it is almost unavoidable to fall into this trap with Husar. Her humour, her intelligence, her vast range of visual interests and influences all tumble onto the canvas—in short, both she and her work are magnetic.

Our conversation soon turns to the situation in Ukraine. She expresses her sadness that the wheel of history has again turned to war. Husar has chosen to examine Ukrainians and Ukrainian-Canadians for the entirety of her career, specifically the way that the culture presents as “a wound covered in makeup.” She explains that when she started painting, nobody was making art about the subject: “when I was first doing this, nobody even knew where Ukraine was. Then Chernobyl happened, and people suddenly knew where it was on the map. And of course, now, everybody knows again.”

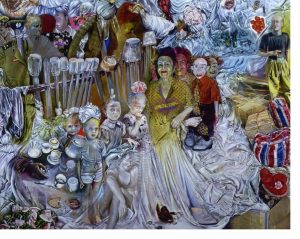

Husar is often labelled as a Ukrainian-Canadian painter, and while her practice is grounded in her Ukrainian origins, to reduce her to her roots is to miss out on the tree that has grown above. When I ask her about her compositions, she tells me that she conceptualizes herself as a theatre director “because I invent characters. I know their names, what shoe size they wear and the shape of their fingers. I think of Ukraine as a metaphorical stage on which these characters can reinvent themselves.”

In the earliest part of her career, Husar made work grounded in her Ukrainian heritage. Her influences were the community, her family—Ukraine through a diasporic lens. She tells me that when she travelled to Ukraine proper, she did not think it would impact her art—”but what I saw there, I couldn’t contain it in my head.”

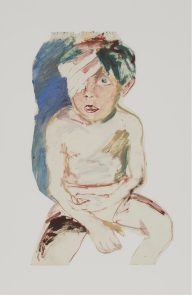

Husar has donated an oil sketch to our Auction for Ukraine, a study for “Pandora’s Parcel to Ukraine,” a 1993 painting held in the permanent collection of the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa. “Study for Wounded Boy (Witness)” is one member of a cast of children destined for the canvas, yet one who never made it into the final painting. Husar explains that the boy represents both a victim of trauma as well as serving as a metaphor for vision. Blinded in one eye, he is still able to see—he is damaged but not broken. She notes that the metaphor is well suited for the current conflict, as war is about perception, about bearing witness.

In Husar’s worldview, art is both prescription and prophecy. She paints without a fixed destination in mind, allowing her unconscious to take precedence at the easel: “I don’t really know why I’m painting something, except that it needs to be painted, because it needs to be pinned down. It will tell me what it is that I’m feeling. That’s what a painting does, often something like 10 years later: it tells you what you felt.”

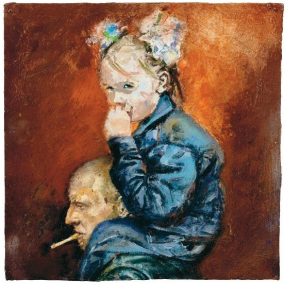

Images painted decades ago return like boomerangs, re-presenting themselves to Husar in her quotidian life. She shows me a 2007 painting, “Burden of Innocence,” which depicts a small girl with pompoms in her hair sitting atop a man’s shoulders. At a recent anti-war protest, the scene repeated itself in real time. Same girl, same pose, as if conjured by the artist. Husar shows me another picture on her iPhone, this one of a group of Ukrainian-Canadian women in a Toronto basement, assembling care packages to be sent to the front lines—echoes of “Pandora’s Parcel.”

Husar believes that a good picture “doesn’t lie—and it’s kind of nice if it winks too.” She explains that the best art “must show you the unarticulated truth, a revelation, something that you have never seen.” She speaks of the great connectivity that art facilitates, “a language that comes in through the eyes.” Our conversation returns to the current auction, and she expresses a hope that buyers approach the auction with great enthusiasm, enabling a hefty donation to be sent to Ukraine. She tells me that she never thought that her work made a real difference—after all, she is not a doctor, nor is she serving on the front lines—but in moments like this, when she is able to contribute a piece of herself, she thinks that it might.

THE UKRAINE AUCTION APRIL 9 – 14

This fundraising auction will be offered online April 9–14. We invite you to view the full gallery and bid now.

100% of proceeds raised will be donated to The Canada-Ukraine Foundation.

Special Terms & Conditions apply to this auction, including no Buyer’s Premium.