Lot 27

LAWREN STEWART HARRIS

Additional Images

Provenance:

Collection of Bess Harris, Vancouver

Estate of Howard K. Harris (COLL I - # 11)

Private Collection, British Columbia

Literature:

Charles Comfort et al., Lawren Harris, Retrospective Exhibition, Seymour Press, 1963, pages 7, 8 and 42.

Dennis Reid, Atma Buddhi Manas: The Later Work of Lawren S. Harris, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, 1985, page 59.

Andrew Hunter, Lawren Stewart Harris: A Painter’s Progress, Americas Society, New York, 2000, page 72.

Note:

Dr. Charles Comfort observed that over the course of an artist's career: “with advancing years, there may be less of the tremendous impact of earlier work but there is a maturity and a sense of harmony and balance that only a lifetime of creative experience can bring to a painting.”

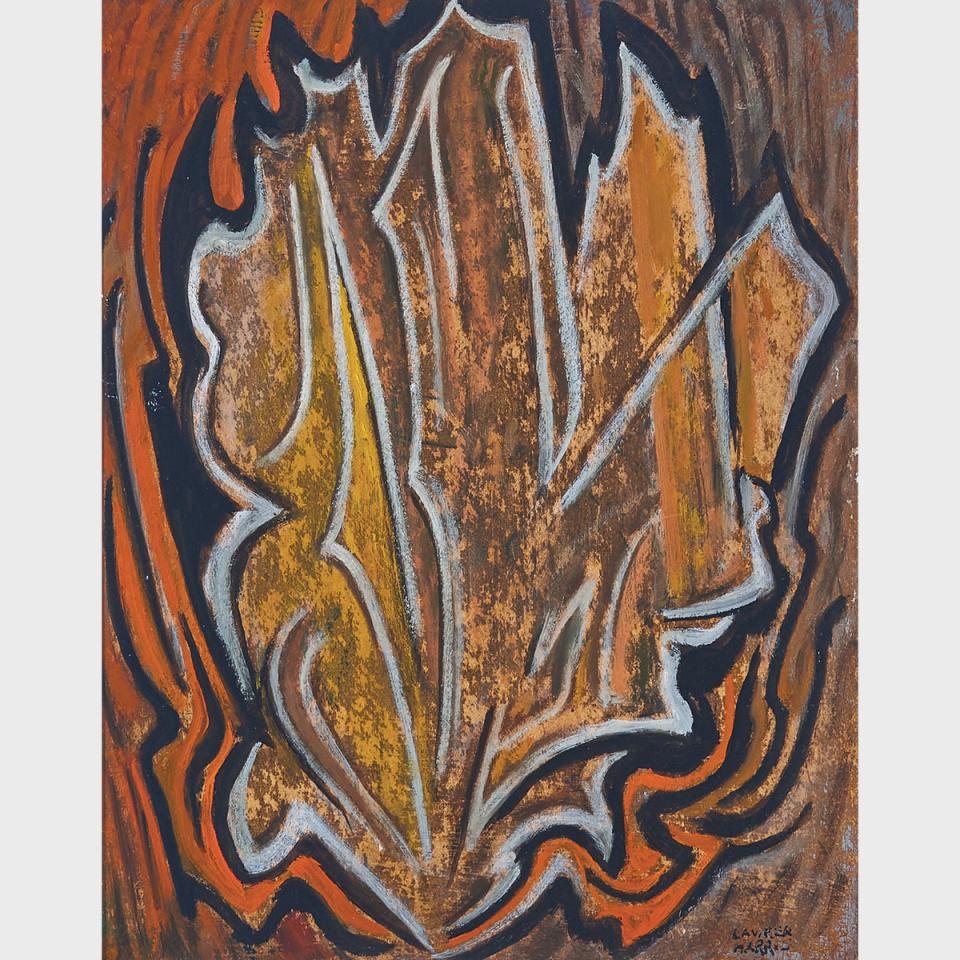

This abstract painting by Lawren Harris (1885-1970) falls within the so-called mature years of his production. According to typewritten labels on the reverse, this sketch was painted in Vancouver, circa 1962. Comfort's position, suggesting as it does, that Harris was “forever reaching for a higher and more exacting phrasing of his own personal and individual vocabulary," seems evident in this lot, painted the same year as Harris's great Atma Buddhi Manas.

From the mid-thirties on, Harris's primary focus was with non-objective painting. While such early works have that "tremendous impact" to which Comfort alluded, works such as this composition exude that "vocabulary which embodies the precision of the purest, at once architectonic, simple, clean, silent and detached” which Comfort insists is the product of maturity.

Dennis Reid has asserted that "all the paintings of 1961 and 1962 are mandala, and they function as, above all else, objects to assist in meditation." If this is to be accepted as fact, surely Abstraction, 1962 holds a special place within this group. Despite his advancing age and a frailty resulting from his 1958 heart attack, Harris continued to paint large, and many works from this period are oversize. This diminutive work stands apart. As a meditative object, it could easily be imagined as the servant of a more private, intense devotion. Fire or the flame motif, found in many religions, holds power as a symbol of purification, warmth, illumination and destruction (possibly, of ignorance). This is Composition’s preoccupation. Reinforcing the central flame shape are bands that radiate out – rhythmically - to the composition’s extreme edges. While Andrew Hunter concedes that “it is not easy to connect with all of Lawren Harris’s later works” admitting that they can be “theoretical and remote,” it must also be conceded that this work, by stark contrast, is an exceptionally sympathetic one, palpably encouraging a strong magnetic pull towards quiet contemplation.