There are no rules… that is how art is born, that is how breakthroughs happen. Go against the rules or ignore the rules, that is what invention is about. – Helen Frankenthaler

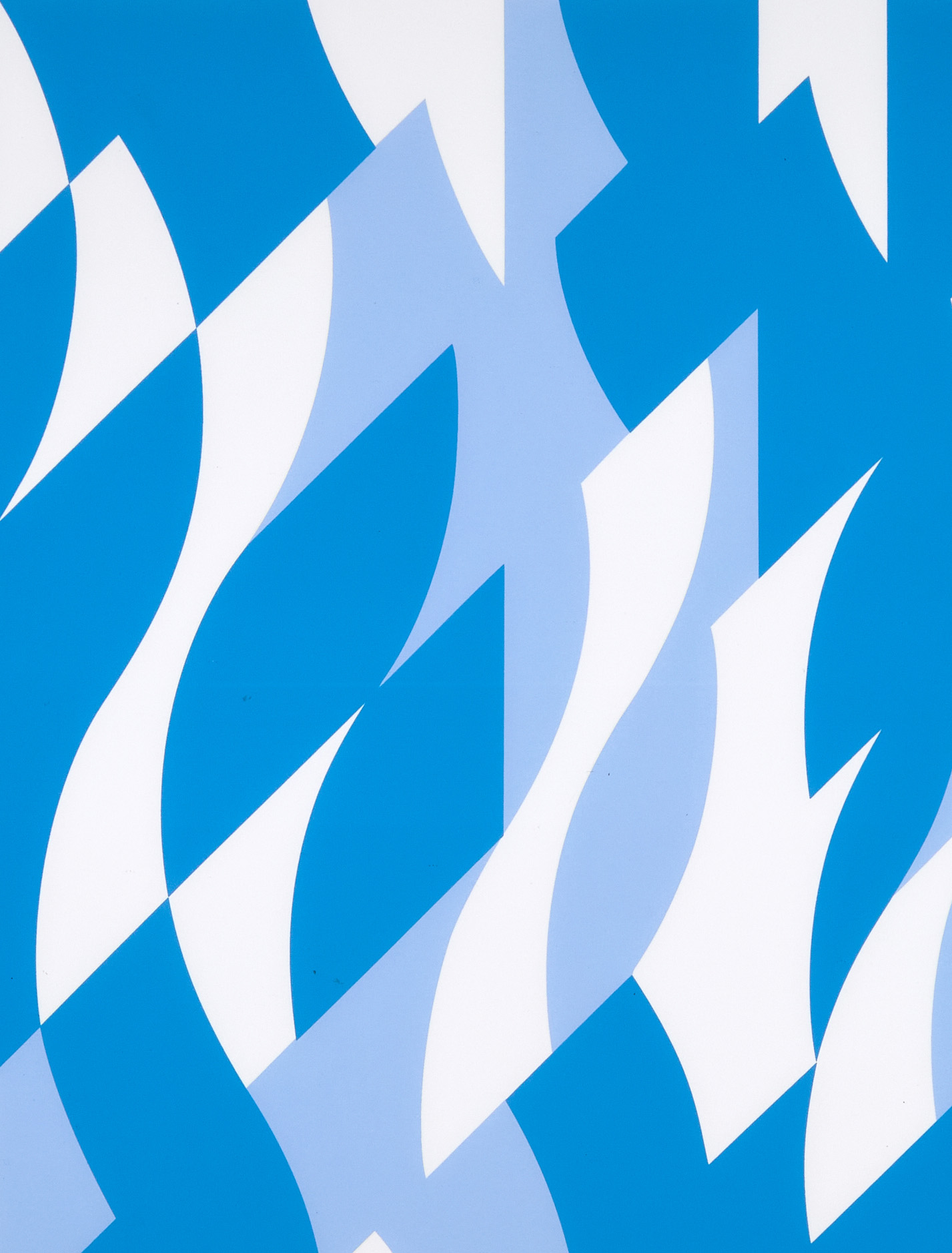

With a career spanning six decades, Helen Frankenthaler, one of the great American artists of the 20th century, was known for her work developing Colour Field painting, also known as Post-Painterly Abstraction. Frankenthaler’s signature works involved a technique of pouring pigment onto raw canvas, inspired by Jackson Pollock’s drip paintings. Unlike Pollock’s thick ribbons of paint, Frankenthaler thinned her pigments with turpentine to create watery washes that were absorbed into the weave of the canvas. Frankenthler’s work expanded the language of abstraction and has had an enormous impact on the course of contemporary art.

Early Life

Born in New York City to a well-to-do family, Frankenthaler’s parents were Alfred Frankenthaler, a Supreme Court judge, and Martha Lowenstein, a German immigrant. Frankenthaler was interested in art from an early age, and studied at the Dalton School and Bennington College. After graduation, she moved to New York City in 1949, and after a brief flirtation with pursuing art history as her métier, she rented a studio and began painting. Her entry into the upper echelons of the art world was facilitated by the influential critic and theorist Clement Greenberg, with whom she was romantically involved for five years. On Greenberg’s urging, Frankenthaler studied painting with Hans Hoffman, who encouraged her to abandon the Cubist style she had been working in so as to pursue pure abstraction.

Through Greenberg, Frankenthaler interacted with artists including Jackson Pollock, Willem and Elaine de Kooning, Franz Kline, and Robert Motherwell, the latter who she married in 1958. Frankenthaler and Motherwell became a glamorous art world couple, known for their lavish entertaining. Professionally, Frankenthaler’s work quickly began attracting notice. In 1950, Adolph Gottlieb included her painting Beach in “Fifteen Unknowns: Selected by Artists of the Kootz Gallery.” In 1951, she joined the Tibor de Nagy gallery, where she had her first solo exhibition that year. Her work was also included in the important “9th St. Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture.”

A Big Breakthrough

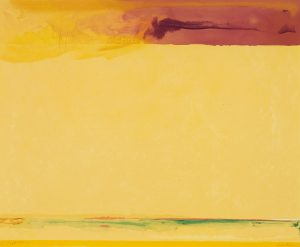

Her great breakthrough – the development of her signature soak-stain technique – came about a year later, in 1952. Frankenthaler’s pivotal work was Mountains and Sea, which was made by pouring coffee cans full of thinned paint onto raw canvas laid on the floor. Stemming from, in Frankenthaler’s words, a “combination of impatience, laziness, and innovation,” the result was translucent fields of radiant colour which evoke the essence of a marine landscape. Frankenthaler noted that it was produced after a trip to Nova Scotia, as an attempt to capture the maritime views.

Of the significance of Mountains and Sea, Adam Gopnik, writing for the New Yorker, explains that “by using the paint to stain, rather than to stroke, she elevated the components of the living mess of life: the runny, the spilled, the spoiled, the vivid—the lipstick-traces-left-on-a-Kleenex part of life.” He also notes that the painting was not an immediate hit, with the Times describing a 1953 show of her work, which included this painting, as “sweet and unambitious.” The term “Colour Field” painting, which would define Frankenthaler’s career, would not be used until eight years later. Mountains and Sea would become, in the words of Robert Hughes, “the watercolour that ate the art world.”

Mountains and Sea formed the foundation of much of Frankenthaler’s later oeuvre, particularly the lush washes of colour, the somewhat raw aesthetic, and what historian E. A. Carmean Jr. suggested was “general theme of place” – a referencing of the physical world. It would become a lens through which viewers saw her paintings, though Frankenthaler shrugged off the idea that her work was about the landscape, telling the New York Times in 1989: “What concerns me when I work is not whether the picture is a landscape, or whether it’s pastoral, or whether somebody will see a sunset in it. What concerns me is—did I make a beautiful picture?”

Major Success – and Backlash

By 1959, Frankenthaler’s work was being included in major international exhibitions. In 1966, she represented the United States at the Venice Biennale, alongside Ellsworth Kelly, Roy Lichtenstein, and Jules Olitski. Her first two major museum exhibitions were in 1960 at New York’s Jewish Museum and in 1969 at the Whitney Museum of American Art, the latter which introduced her work to a wider and more mainstream audience.

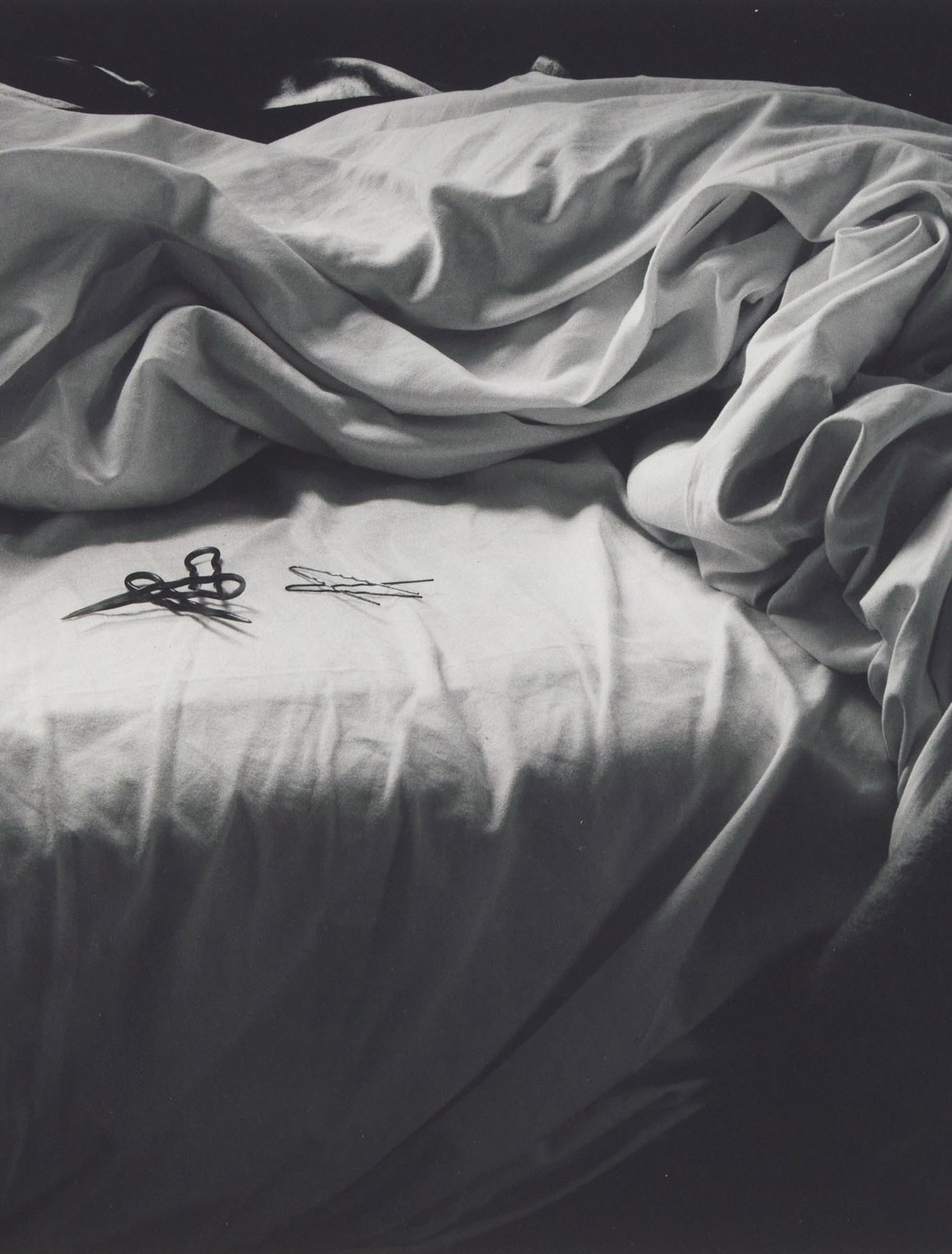

Frankenthaler’s gender was a source of fascination and sometimes derision in the male-dominated art world of the period. One of only a handful of female Abstract Expressionists, Frankenthaler was adamant that her work and her gender had nothing to do with each other. Some critics viewed her abstractions as overly feminine, which was meant to imply that the work was too decorative. Others viewed her soak-stain technique as reminiscent of menstrual stains, with fellow painter Joan Mitchell calling her a “Kotex painter.”

It is no wonder that when the feminist movement emerged in the 1970s, Frankenthaler resisted being viewed as a “woman painter” or having her gender discussed in the context of her work. In John Gruen’s book “The Party’s Over Now” (1972), Frankenthaler explained that “for me, being a ‘lady painter’ was never an issue. I don’t resent being a female painter. I don’t exploit it. I paint.”

Printmaking

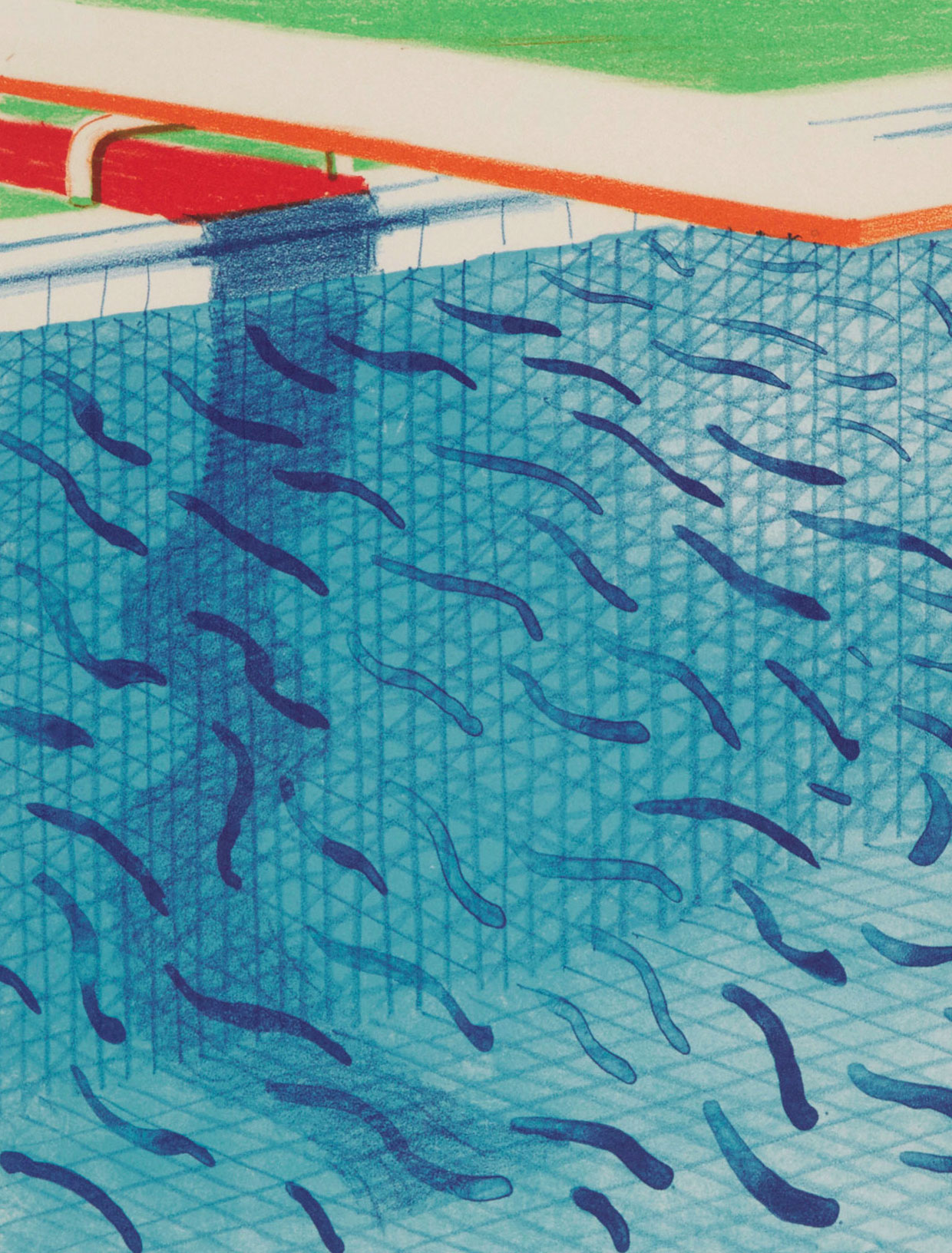

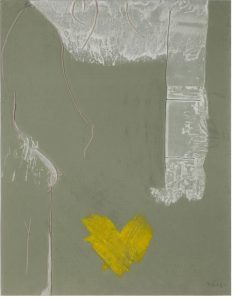

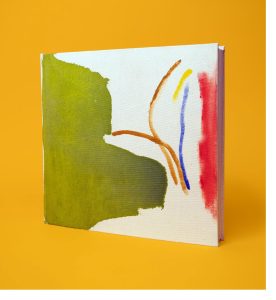

Frankenthaler experimented with ceramics, sculpture, tapestry, and especially printmaking. Her works on paper are an important part of her oeuvre, and situate the artist as an important member of the resurgence of interest in printmaking in the mid 20th century. An offshoot of her painting practice since 1961, the artist’s woodcuts, lithographs, etchings and screenprints attempt to capture the vibrant colours and expressionistic forms of her works on canvas.

A seminal woodcut, East and Beyond, is cited as influencing the medium as a whole. Frankenthaler was inspired by the work of Utagawa Hiroshige, particularly the subtle colours used by the Japanese master. The New York Times describes East and Beyond as being “to contemporary printmaking in the 1970s what Ms. Frankenthaler’s paint staining in Mountains and Sea had been to the development of Color Field painting 20 years earlier.”

Frankenthaler’s prints have been widely exhibited, often as compliments to her paintings. In assembling a 2017 exhibition, curator Jay A. Clarke explained that Frankenthaler “was not content to use earlier methods of production; she wanted to push herself in new directions and allowed herself to be encouraged and challenged by the printers and publishers with whom she collaborated. Frankenthaler’s paintings were created in the isolation of her studio, but the process of carving and printing woodblocks in collaboration with others brought new challenges to the artist—ones she relished.”

Later Career

Motherwell and Frankenthaler divorced in 1971. She married an investment banker, Stephen M. DuBrul Jr. in 1994. The couple bought a house on Long Island Sound in 1999, the views from which would influence her later imagery. Maritime colours would permeate these works, saturated with greens and blues.

Frankenthaler’s influence on contemporary art was monumental, and continues to grow after her death. She made art into her final years, shifting from oil to acrylic paint, which had the effect of making later paintings less translucent. The result was denser, more intense compositions which were bolstered by Fankenthaler’s more intense palette. Her goal, in the words of her nephew Clifford Ross, was to create “a richer, slower sense of how you perceive a picture, how you read a picture.” As for how to achieve that goal, Frankenthaler approached each piece as its own unique entity – “there is no formula. There are no rules. Let the picture lead you where it must go.”

About the auction

Held online from April 20 – 15, 2024, our Editions auction features work by Keith Haring, Helen Frankenthaler, Christopher Wool, Friedel Dzubas, Roy Lichtenstein, Jean Paul Riopelle, Kiki Smith, Sonia Delaunay, Bridget Riley, Alfred Pellan, Sol Lewitt, Terry Frost, Yoshimoto Nara, and Brice Marden, alongside classic prints by Francisco de Goya, Pablo Picasso, and Joan Miró.

The auction will be available for preview at our Toronto location:

Monday, April 22 from 10:00 am to 5:00 pm

Tuesday, April 23 from 10:00 am to 5:00 pm

Or by appointment.

Please contact us for more information.

Related News

Meet the Specialists

Goulven Le Morvan

Director, International Art, Montreal

Alicia Bojkov

Consignment Specialist, International Art