netsuke: A solution to solving a sartorial problem

While netsuke have a devoted following, we thought we’d create a primer for those interested in starting a collection or looking to expand their knowledge of this unique artform.

What Are Netsuke?

Netsuke (pronounced “net-skay”) are small carved ornaments designed to solve a particular sartorial problem posed by the traditional kimono: neither male nor female versions have pockets. A woman’s kimono has sewn-up sleeves, which creates a sort of pouch where items can be stored, but men’s kimono are entirely open from front to back. As a solution, men would suspend necessary articles such as tobacco, medicine, writing implements and seals from silk cords. Collectively, these items are known as sagemono, meaning “hanging things.” These cords were worn looped behind the belts used to keep a man’s kimono in place, with the netsuke acting as a counterweight or anchor at the other end of the cord, thus ensuring that items would not slip from the belt. A decorative bead known as the ojime slid along the cord between netsuke and sagemono to tighten or loosen the arrangement, allowing access as needed.

The Significance of Netsuke

Over time, netsuke evolved from beyond a problem-solving toggle and into an artform in their own right. Feudal Japan had a strict caste system with strong sumptuary laws in place—laws which tightly regulated the types of materials, fabrics and dwellings that were accessibly to each caste. The Samurai warrior class sat at the top of the hierarchy, followed by farmers, artisans and merchants, in that order. Members of the merchant class, while relegated to the bottom rung of society, could often be more prosperous than members of the warrior class, but due to the sumptuary laws had few outlets through which they could display their material success. Netsuke, being small and relatively discrete, offered a loophole. Rare materials and clever carvings enabled a degree of conspicuous consumption and allowed the wearer to express themselves within the limits of the law.

Materials & Themes

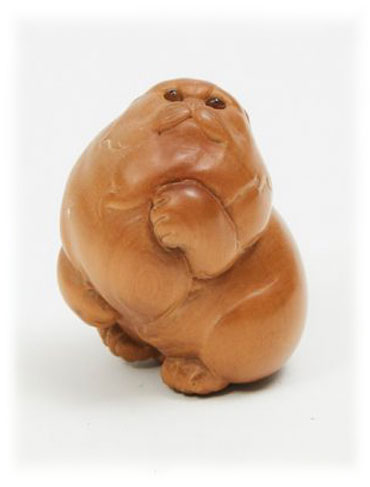

Netsuke were often carved from ivory or wood, with the majority of extant pieces being made of the latter. Other materials included coral, shells, metal, ebony, porcelain and even nuts.

Netsuke carvers were wildly inventive, with subjects ranging from mythology, history and nature to the erotic, satirical and the grotesque. Forms often mirrored trends in mainstream Japanese art and culture, and reflected the temperament, wit and/or interests of the wearer. It was even possible to be quite daring with one’s netsuke choice and select a risqué subject matter—say, poking fun at one’s superiors—as netsuke were easy enough to conceal from authorities.

Collector’s Items

Netsuke were widely collected during their day. In a way, they are comparable with contemporary interest in handbags or watches, inasmuch as a prosperous man would often have a range of netsuke, and would select one to wear according to the occasion or outfit.

Japan ended its isolationist policy in 1853; the influx of foreign culture brought with it a rise in the popularity of Western dress among the local populace. Accordingly, the kimono receded into private life and demand for netsuke as items of fashion declined. However, Western interest in the items soared as netsuke were seen as a brilliant collector’s item—a perfect, portable souvenir from a different culture. The art form has not died out with the decline of traditional dress, with contemporary netsuke carvers working in both Japan and abroad.

Of note for new collectors: netsuke can be signed or unsigned, and the presence of a signature does not always determine value. Often, if an artisan was creating something for a client well above their station, they would omit their signature out of respect. Similarly, lesser artists and copyists were known to use the signature of master carvers.

Interested in learning more?

We’re always happy to chat or provide additional images and condition reports, even while we’re working from our home offices! Contact a member of the Asian Art department:

Amelia Zhu, Specialist:

[email protected]

416-847-6185

Austin Yuen, Specialist:

[email protected]

416-847-6185

Related News

Meet the Specialists

Austin Yuen

Specialist

Amelia Zhu

Senior Specialist / Business Development