十九/二十世纪 铜胎掐丝珐琅鼻烟壶一组三件

tallest height 3.3 in — 8.5 cm

Estimate $400-$600

Snuff bottles hold a unique place in the rich history of Chinese art.

Like the Japanese netsuke, they represent the marriage of function and artistry—initially implemented to solve a problem, but soon evolving into a distinct artform of their own. Snuff bottles are truly emblematic of the Qing Dynasty culture (1644-1911), having been introduced at the beginning of this period and falling out of fashion by the end. Initially a rare commodity reserved for the elite, snuff and its bottles ultimately permeated nearly all segments of the vast Chinese Empire. Snuff bottles were effectively only in use for around 300 years—a very small period within the 5000+ year history of Chinese art. Though small, collectors today appreciate snuff bottles for their beauty, rarity, cultural significance and superb craftsmanship.

What is snuff?

Tobacco, a crop indigenous to the New World, had been introduced to Asia by way of Europeans who themselves imported it from the Americas. Snuff is a concoction composed of finely ground tobacco leaves mixed with aromatic herbs and spices that is inhaled through the nose. Most histories suggest that snuff was introduced to China by European missionaries, envoys and traders in the mid 17th century, while others imply that it came by way of Japan, Russia or from invading Manchus. While at the time, the Chinese regarded the smoking of tobacco to be distasteful, snuff was seen to have medicinal value. Sniffing the substance often provoked sneezing, which was seen to be a method of purging impurities and disease. Regardless of its specific point of entry, it quickly caught on with members of China’s social elite and imperial family, becoming a sign of wealth and status—as well as an expensive habit.

The Emperor Kangxi and the origin of snuff bottles

The Kangxi Emperor (1654–1722), second ruler of the Qing Dynasty, is widely credited for the introduction of snuff bottles. It is said that Jesuit missionaries, in a bid to gain access to the Forbidden City, presented Kangxi with an elaborate snuff box. Pleased with the gift, Kangxi quickly realized that China’s humid climate would cause the snuff to clump up in the loosely sealed box. He suggested that the snuff be decanted into traditional Chinese medicine bottles, and commissioned delicately handcrafted versions for himself and his inner circle.

Snuff bottles were designed with portability and the preservation of its contents in mind. Exquisitely tiny, snuff bottles are rarely more than three inches high, designed to fit comfortably in the hand. Bottles were also equipped with an airtight cork stopper to keep flavours fresh. Snuff bottles can be found in a range of materials including wood, porcelain, jade, metal, ivory, stone, gemstones and glass. All authentic Chinese bottles are handmade. Even porcelain examples—the least expensive and most easily reproduced—are typically hand-painted and hand-finished. The production of snuff bottles is enormously laborious, often taking skilled craftsmen weeks to complete.

Kangxi was very particular about his bottles, and in 1695, set up an Imperial workshop devoted to their production. Kilian Stumpf, a Bavarian Jesuit priest, was put in charge of the glass manufacture, where he would introduce local artisans to Western techniques in glassblowing and enamelling. Western styles such as the Rococo would continue to filter from West to East, influencing Qing decorative expressions. The history and evolution of snuff bottles is founded on this unique collaboration between East and West, as Chinese craftsmen learned new techniques, adapting and perfecting them to create uniquely Chinese interpretations. This new artistic fusion—as well as the widespread adoption of a Western habit—also signalled a growing acceptance of the West and its culture and a relaxing of China’s previous isolationist policies.

The evolution and decline of the artform

清 藓纹玛瑙鼻烟壶

height 3 in — 7.7 cm

Estimate $300-$500

The most coveted snuff bottles come from the Imperial court of Yongzheng (1678–1735) and Qianlong (1711–1799), who enthusiastically supported the development of this art form. Often the finest examples from this period are enamelled—a technique learned from the Jesuits—and might have European motifs, such as Catholic iconography. This is not to suggest that Western forms dominated the genre, for craftsmen imbued these bottles with all manner of elements from Chinese culture—mythology, folklore, Confucianism, Buddhism, Taoism and requests for good fortune, with a popular motif being the wish for positive Imperial examination results. Yongzheng and Qianlong were also partial to bottles designed to resemble something else, such as a glass bottle that resembled coral, jade, or stone.

Extremely prestigious, the actual function of snuff bottles was wildly surpassed by their role as status symbols in the Qing period. Scholars often compare the cachet of snuff bottles to that of a modern-day Rolex watch: something covetable, highly portable, indicative of refined taste, and easy to show off in polite company. While never considered to be high art, they were seen as especially precious items, resulting in their being given as gifts, bribes or a means of paying for goods and services.

By the 1880s, farmers in Asia had begun to grow tobacco locally, which resulted in a steep decline in its cost. This new availability allowed greater swaths of the population to partake in snuff, and the habit spread throughout the empire. No longer the realm of the Imperial court and the very wealthy, cheap and even disposable snuff bottles soon flooded the market to supply the general population.

During the transition from the Qing Dynasty to the Republic era, snuff fell out of fashion, replaced by the more modern habit of smoking of cigarettes and pipes. Snuff bottles are still being manufactured as collectible items, though any bottle dated to the 1920s and after holds less allure for serious connoisseurs.

We are pleased to offer a selection of superb examples of Chinese snuff bottles in our December Asian Art auction. To view these lots, please click here.

AUCTION INFORMATION

The final Asian Art auction of 2020 will be offered online from December 5-10.

Please note that all transactions are in Canadian Dollars (CAD) and all times posted are ET.

We invite you to view the full gallery, which includes export porcelain from the Estate of Johannes Van Wees, Victoria, including ceramics from the Nanking Cargo and the Hoi An Hoard. Other collectible highlights include a continuation of white jade carvings from a Toronto family collection, late Qing and modern Chinese paintings, and three suits of samurai armour.

Contact us for condition reports, additional photos or information. Whether you are based in Canada or abroad, we are here to serve you by telephone, email or secure video link.

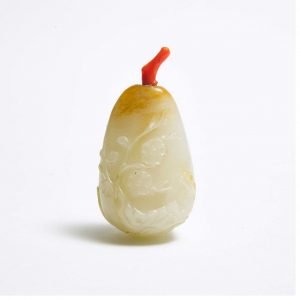

十八世纪 白玉俏色雕梅竹纹鼻烟壶

length 2.8 in — 7.2 cm

Estimate $600-$800

十九世纪 银丝嵌宝青白玉鼻烟壶

height 3.1 in — 8 cm

Estimate $600-$800

十九/二十世纪 琥珀巧雕双瓜纹鼻烟壶

height 2.7 in — 6.8 cm

Estimate $300-$500

Related News

Meet the Specialists

Amelia Zhu

Senior Specialist / Business Development

Austin Yuen

Specialist