The idea of the “Chinese scholar” dates back to as early as the Warring States period (475-221 B.C.), and beginning in the Sui dynasty (581-618 A.D.) it was decided that the selection of civil servants for the state bureaucracy should be determined by the Civil Service Examination. This series of merit-based examinations was designed to assess proficiency across a wide range of subjects, including knowledge of Confucian and philosophical texts, history, law, agriculture, painting, calligraphy and music. Preparing for these examinations took years. Those who excelled were offered roles in the Imperial government, which was a gateway to a life of politics, privilege, and social status.

“Scholar’s objects” refers to items used or displayed by a Chinese scholar in his studio. These items included both the functional (table and chairs, screens, boxes, brushes, water droppers, trays, objects for making and serving tea, etc.) as well as the inspirational (scholar’s rocks, scrolls, small decorative items, etc.), all carefully selected for their beauty as well as for their abilities to foster creativity and contemplation. Scholar’s objects represent the pinnacle of Chinese artistry, aesthetics and technical precision, cultivated over thousands of years. Scholars were both creative intellectuals and collectors of sophisticated art objects, and the items they displayed embodied traditional culture while also representing the specific curiosity, taste and intelligence of their owners.

Stylistically, the decorative elements of scholar’s objects echo Chinese art at large. Human figures and animal motifs abound, including immortals, Buddhist figures, dragons, and other symbolic, mythological and religious entities. Nature and its oneness with mankind is another important aspect of scholar’s objects, and the idea of returning to nature and one’s natural state is an important part of the scholarly ideology. This stems partly from Chinese culture, but another important piece of the concept comes from the history of Chinese scholars. If and when a scholar fell out of favour with higher powers, they would retire from government service and take refuge in the countryside. Either alone or part of groups of like-minded individuals, these exiled scholars would devote themselves to artistic pursuits, inspired by nature rather than more formal courtly styles. By the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties, relative peace meant that the need to seek refuge in the wilderness became rarer, but the scholarly taste for the romance of nature persisted. Though situated in more developed urban locales, Ming and Qing scholars liked to imagine themselves in the wilderness like their predecessors, and built their studies to face gardens, water features, and interesting rock formations.

Scholars’ studios were designed to be clean, quiet and calm, tucked away from worldly pursuits. There, scholars would study Confucian texts, play music, contemplate antiquities, and work at the “three perfections”: poetry, painting and calligraphy. The cornerstone objects of the scholar’s studio are referred to as the “four treasures,” which distinguished him from a common tradesman: writing brush, ink stone, ink, and paper. Complimentary items were made from a range of materials including wood, lacquer, cloisonné, bamboo, stone, ivory, metal and ceramic.

A scholar’s studio often included the following items:

Brush Pot and Brushes:

Historians can trace the brush’s origins in China back to the third century B.C. Calligraphy and painting were central to the scholar’s arts, and a brush could be considered the most important object within it. Brush pots would keep the scholar’s tools tidy and at hand, and can be found in a variety of mediums including porcelain, wood, ivory, jade, glass and bamboo. Brushes would be placed handle-down into the pot so that the delicate bristles could maintain their precise shape. Brush pots range from simple to ornate.

清 十八世纪 竹刻莲塘图笔筒

height 4.3 in — 11 cm

Estimate $1,500-$2,000

Brush Washer

Used to remove excess pigment from the brush, a brush washer is a relatively shallow dish filled with water, indispensable for calligraphy and ink painting. Though a functional object, brush washers were elevated into works of art by skilled craftsmen. Materials include jade, porcelain, exotic woods, bamboo, and glass.

明 白玉雕荷叶洗

length 4.1 in — 10.5 cm

Estimate $5,000-$7,000

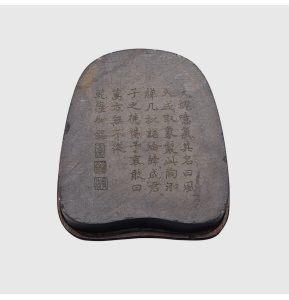

Inkstone

The earliest extant inkstone dates back to the 3rd century B.C. Out of the “four treasures,” it is the inkstone which was considered the most important. An inkstone is a stone mortar for grinding and holding ink. A sunken well at one end of the inkstone would hold the pooled ink for the scholar to dip his brush into. A good inkstone allowed the scholar to evenly grind a finer ink. The finer the ink that a scholar could grind, the better the ink flow and the more pleasing the art—hence the importance of a good inkstone.

Table screen

A scholar’s painting table was typically situated in front of a window for catching the best light. The table screen would be placed in front of the window to protect the scholar and his painting surface from wind and direct sun.

Objects for admiration

A scholar’s table was decorative as well as practical, and included beautiful objects, jades and sculptures. “Scholar’s rocks,” also known as “viewing stones”, are among the most prominent of these objects, appreciated since the Song dynasty (960-1279). Scholars would rarely venture into nature to work en plein air, but would instead find inspiration from the natural world through representative objects. Robert D. Mowry, Harvard Art Museum’s Curator Emeritus, explains that “like a landscape painting, the rock represented a microcosm of the universe on which the scholar could meditate within the confines of his studio or garden. Although most scholar’s rocks suggest mountain landscapes, these abstract forms may recall a variety of images to the viewer, such as dragons, phoenixes, blossoming plants and even human figures.” Scholar’s rocks were sourced from nature, often from remote areas. Naturally occurring or enhanced by skilled carvers, they can range from very large to very small.

灵璧赏石

带硬木座

length 26 in — 66 cm

Estimate $600-$800

Wrist Rest

Because calligraphy is written vertically from right to left, scholars needed to take precautions against smudging. Wrist rests helped keep the wrist elevated and well steadied when writing or painting. Most wrist rests were made from carved bamboo.

二十世纪 牙雕加彩人物臂搁一对

with stand height 8.1 in — 20.5 cm

Estimate $800-$1,200

About the auction:

Sourced from collections across Canada, highlights from our Asian Art auction, online from June 24 — 29, 2023, include a Kangxi mark and a period ‘dragon’ dish from the A.W. Bahr collection, a Qianlong mark and period gilt bronze Chakrasamvara figure, Guangxu and Tongzhi mark and period bowls, and paintings by Fan Zeng (b. 1938) and He Baili (b. 1945). Works sourced from important private collections including Ming and Qing porcelain, jade and cloisonné wares, Longquan celadon, imperial embroideries, scholar objects, Himalayan and South Asian sculpture, and Japanese works of art.

沃丁顿亚洲艺术六月大拍很荣幸为您呈现一批横跨加拿大、

On View:

Sunday, June 25 from 12:00 pm to 4:00 pm

Monday, June 26 from 10:00 am to 5:00 pm

Tuesday, June 27 from 10:00 am to 5:00 pm

Please contact us for more information.

We invite you to browse the full gallery.

Related News

Meet the Specialists

Amelia Zhu

Senior Specialist / Business Development

Austin Yuen

Specialist