Throughout the millennia, representations of dragons have been deeply integrated into Chinese art across a variety of mediums. Its various depictions highlight the dragon’s pivotal role as a representation of the divine, a symbol of imperial authority, and a dynamic force capable of warding off malevolent influences through its role as a benevolent deity, believed to bring auspicious events such as rainfall and foster life on earth. The 2024 Lunar New Year marked the arrival of the Year of the Dragon, the only year named after a fantastical creature. As a result, the dragon is the most celebrated creature out of the twelve zodiac animals. As tribute to this tradition, the Royal Ontario Museum exhibits a set of twelve porcelain zodiac animals in the Joey and Toby Tanenbaum Gallery of China (Image 1), and is rotated every Lunar New Year to showcase the present year’s zodiac animal front and centre.

千百年来,中国艺术中对龙的呈现形式可谓丰富多彩,数不胜数。无尽关于龙的描绘突显了龙作为神权、皇权的象征,通天彻地,驱邪攘灾,纳祥转运,护佑苍生,成为中华民族的精神图腾。

2024年的农历新年标志着龙年的到来,作为十二生肖中唯一没有在现实世界中被发现的生物,龙也因此成为最特殊、最受欢迎的生肖之一。为了纪念生肖民俗文化的传统,加拿大皇家安大略博物馆在主楼一层中国艺术(约瑟夫和托比·塔南鲍姆)展厅展出了一套三彩瓷塑十二生肖(图1),每逢农历新年都会轮换展出本年的生肖动物,将其置于一列最中心位置,供游客观赏。

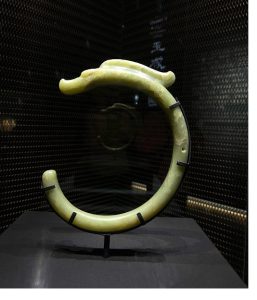

Today, the dragon is commonly understood as a blend of various features: stag antlers, an equine head, rabbit’s eyes, a serpent’s body, fish scales, eagle talons, and other superfluous features. However, during ancient times, dragons were entirely creations of imagination, and traditions varied regarding the dragon’s attributes. Interpretations ranged from bodies of lizards, crocodiles, and serpents, to the heads of horses, cows, or pigs. One of the earliest discovered representations of a dragon in China dates to the 5th to 3rd millennium BC from the Hongshan culture, which is featured in a celadon nephrite jade “C-shaped dragon” carving. (Image 2) This dragon bears a long protruding snout that terminates in a truncated and upturned manner with paired fusiform protruding eyes, resembling a pig’s head. The example pictured below is held in the Palace Museum Collection, Beijing, and once belonged to the collection of Professor Fu Zhongmo, a celebrated academic in the field of Chinese jade.

现今龙的形象普遍被认为是人们将若干动物肢体和特征组合成的神物,如鹿角、马首、兔眼、蛇身、 蜃腹、鱼鳞、鹰爪等。然而在古代,龙完全是古人丰富想象的产物,人们对其形象属性的看法各不相同,古时对龙的描绘更接近于类似蜥蜴、鳄鱼和蛇的身体,以及马、牛或猪的头部。中国发现的最早的龙的形态之一可以追溯到公元前5至3世纪的红山文化,(图2) 这条青黄玉龙整体形状呈C字型,龙首长鼻突出,末端短而上翘,梭形长眼狭长耸出,酷似野猪,颈部有类似背鬃的形状并向卷起,尾部较钝,全身光素无纹。如下图所示,此玉龙现藏于北京故宫博物院,原为古玉研究专家傅忠谟先生收藏。

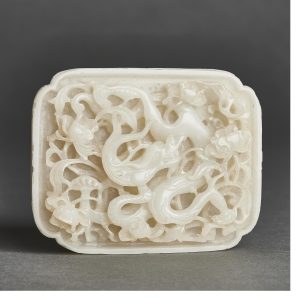

Following the transition to the Shang dynasty (1600-1100 BC), both the spiritual authorities and the royal authorities held significant importance. Earlier Neolithic cultures such as the aforementioned Hongshan culture are characterized by jade artifacts used for sacrificial rituals and reverence to deities. The Neolithic period is commonly referred to as the “jade age of gods”. Conversely, the Shang period is referred to as the “jade age of kings”, where jade artifacts were predominantly used for adornment and decoration by the royal family. As a result, wearing jade artifacts with dragon motifs was a clear indication of the wearer’s status and authority. Such artifacts were undoubtedly owned and enjoyed solely by individuals within the inner circle of the ruling class, and represent a high level of development in jade craftsmanship and production capabilities during the Shang dynasty. The jades from this period also reflect mainstream aesthetics and cultural attributes of that era. One such Shang dynasty depiction of dragons can be found in a jade carving that sold at Waddington’s Auctioneers and Appraisers in Toronto on December 7th, 2023 (Image 3), previously from the collection of Albert Y.P. Lee (Li Erbai) and Sara K.S. Lee (Luo Guisheng), descendants of the famous Chinese statesman in 19th century Li Hongzhang (1823-1901). This piece is a vivid and intriguing image. Its small size and drilled aperture at the tail both point towards its function as an ornament, signifying its role as an object of enjoyment for royal nobility.

商代(公元前1600-1100年),是一个神权与王权并重并链接紧密的时期。早期的新石器时代,比如前文提到的红山文化,对玉器的使用限于祭祀仪式和神灵崇拜。新石器时代通常被称为“神玉时代”。而商代则转变为“王玉时代”,所生产玉器大多为王室佩戴、把玩装饰使用。因而能够佩戴带有龙纹饰的玉器更是成为了王室特权和身份地位的象征。此类玉器制品无疑专供统治阶层内部阶级享有,代表了商代玉器制作的工艺和生产能力的最高水平,同时反映了当时的主流审美和文化属性。具体可参考沃丁顿拍卖2023年12月7日售出的一件商代青白玉龙佩 (图3),该藏品属于十九世纪中国著名政治家李鸿章(1823-1901年)家族后代李尔白及夫人骆桂生伉俪重要青铜器及玉器珍藏。玉龙形态写实、生动有趣。小巧的尺寸和尾部的钻孔都表明其作为佩饰的功能,以及其专供王公贵族享受的珍贵身份。

图3,青白玉龙 商 (1600-1100 BC) 李尔白及骆桂生伉俪珍藏重要青铜器及玉器,由李尔白先生于1978年11月4日购自纽约苏富比,拍品编号176,后由加拿大沃丁顿拍卖于2023年12月7日售出

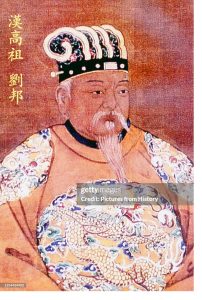

Prior to the Qin dynasty (221-206 BC), the dragon held significance as an object of reverence, associated with state leaders and ancestors, and its imagery was not tied to any particular individual. However during the Qin dynasty, the portrayal of the dragon became standardized, reflecting centralized governance of a nation and serving as one of the many tools used by the emperor to justify his rule. Qin Shi Huang (259-210 BC), the first Emperor of China, adopted titles such as “the Emperor of the Dragon Throne” and “Master of the Waters.” Later rulers and nobility continued to exploit the dragon’s dual symbolism as a representation of both ancestral and military power. One notable example is Liu Bang (256-195 BC)(Image 4), later known as Emperor Gaozu and the first emperor of the Han dynasty (206 BC-AD 8), who claimed to have been conceived after his mother encountered a dragon during a rainstorm. In following this philosophy, subsequent emperors referred to themselves as the “Heavenly Son of the Dragon”, and adorned imperial chambers, garments, tombs, and even everyday imperial objects with dragon motifs.

秦朝(公元前221-206年)之前,龙作为通天神兽,其形象与王权和先祖联系在一起,并不代表任何独立个体,直到秦始皇(公元前259-210年) 统一中国。作为中国的第一位皇帝,秦始皇将龙的形象标准化,并以“祖龙”自居。此举不仅反映了国家的集权统治,并成为皇帝用来巩固皇权、证明其统治合法性的众多工具之一。秦之后的历代君主都继续利用龙的双重象征意义实现对绝对权利的掌控。 相传汉朝的第一位皇帝,高祖刘邦(公元前256-195年)(图4)其母亲在暴雨中遇龙后怀孕,诞下刘邦,因此他被称为“真龙天子”。随后的 历代帝王纷纷效仿,并在宫廷、服饰、陵墓及皇家日常用品上饰以龙纹,彰显权力和神圣地位。

图4,汉高祖刘邦像 清绘 图片来源:Getty Images

It was only during the Song dynasty (960-1279) that the dragon became exclusively associated with the emperor, as decreed by Emperor Huizong (1082-1135), and imposed a penalty of two years’ imprisonment for offenders. As a result, depictions of the dragon during this period would have been directly commissioned by the imperial court. The highest value achieved at auction by a Chinese work of art depicting a dragon is held by a painting by the Southern Song court painter Chen Rong (1200-1266) titled “Six Dragons”, which sold for $48,967,500 USD. Chen Rong was celebrated for his paintings of dragons, and this particular work was deaccessioned from the Fujita Museum, Osaka. A meticulous lineage of documentation traces the painting back to the collection of Emperor Qianlong (1711-1799) later in the Qing dynasty. Most importantly, it was documented in the Shiqu Baoji, a prestigious inventory that catalogued Chinese paintings and calligraphic pieces within the imperial Qing collection. Just as Chen Rong’s dragon was favoured by the dignitaries at the time of its creation, his depictions set the standard for dragon imagery in the centuries that followed.

直到宋朝(960-1279年)期间,龙才成为皇权的专属代表。宋徽宗(1082-1135年)曾颁布法令规定龙纹仅为皇家尊用,对违者处以两年监禁的处罚。因此,带有龙纹装饰的物品非常有可能为宫廷直接管辖制作。迄今,中国“龙”艺术品最高拍卖纪录由南宋宫廷画家陈容(1200-1266年)所作《六龙图》以售价48,967,500美元 (约合人民币超三亿元) 的惊人记录所保持。陈容字所翁,以画龙而闻名,笔墨简洁而精妙,故世有“所翁龙”之称。此幅《六龙图》为日本藤田美术馆旧藏,流传有序,品相完好。最重要的传承是其曾为清代乾隆皇帝(1711-1799年)珍藏,并收录在专门记载清代内府收藏的历代书法和绘画的专书《石渠宝笈》中。乾隆皇帝更提笔在画作中央留下行书诗一首以表喜爱之情。陈容“所翁龙”的高超艺术水准为后世龙形象的发展奠定了基础。

Link: https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-6061275

图5,陈容 (宋)《六龙图》局部,设色纸本 手卷,纽约佳士得“宗器宝绘—藤田美术馆藏中国古代艺术珍品”专场,2017年3月15日,售价$48,967,500美金

The Yuan dynasty (1279-1368) saw further regulations on the use of dragon symbolism, reserving the depiction of five-clawed dragons solely for the emperor, while princes were permitted to use four-clawed dragons. Unlike the earlier depictions, Yuan dragons were ferocious and mighty, and paired with a free and vivacious charm, were closely related to the spirited rule of the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. Emperor Shizu (1215-1294), also known as Kublai Khan, established the Bureau of Gold and Jade in Hangzhou and Dadu (modern-day Beijing), which oversaw thousands of skilled jade artisans. These jade production centres were tightly regulated in order to supply jade exclusively for imperial use. The decoration, carving techniques, and craftsmanship during this period were remarkably exquisite, and showcased a distinct style unique to the Yuan dynasty. Such artifacts inherited a lineage of carving styles and techniques from jade artwork from the Song, Liao, and Jin dynasties. Many pieces took the form of double-layered openwork design on panels or belt ornaments. One such example was sold at Waddington’s Toronto in September 2023, which depicted a five-clawed dragon carved reticulated on a white jade belt plaque (Image 6). Jade pieces from this period demonstrated the innovative and sumptuous spirit of these northern ethnic groups towards jade crafting culture, which were a consequence of the strong political might and prosperous economy. This tradition laid the groundwork for the evolution of jade carving in the following Ming and Qing dynasties.

到了元朝(1279-1368年),统治者对龙纹的使用进行了进一步的规范化,设定“五爪龙”仅为皇帝专用,皇子则可使用“四爪龙”。与早期的描绘不同,元代的龙形象凶猛而强大,充满动感与张力,或许与彼时蒙古族领导者骁勇善战和血气方刚的形象相符合。元始祖忽必烈(1215-1294年)在杭州设立了官办金玉总管府,直接管辖南方数千名玉雕工匠,使北方的大都(今北京)与南方的杭州成为元代南北玉器生产制作中心。这些官方管理的玉器生产机构管理严格,专门为皇室提供宫廷用玉。这一时期的装饰、雕刻技术和工艺精美绝伦,展现了元代独特的风格。上承宋、辽、金玉器雕刻风格和技术,元代玉雕造型古朴但却工艺精湛,许多牌佩类及带饰采用透雕,浮雕,双层镂空设计。以下面这件罕见元代白玉高浮透雕穿花龙纹蹀躞为例,温润坚密的白玉厚料深刀立体地雕琢出一条五爪龙,蜿蜒穿行于纷繁翻卷、枝梗交错的花叶中,层次丰富,立体感极强。这一时期的玉器展示了北方民族对玉雕工艺的创新和不惜工本的奢华气度,这是强大的政治力量和繁荣的经济的果实,并奠定了随后明清时期玉雕艺术发展的基础。

图6,白玉高浮透雕穿花龙纹蹀躞 元 (1279-1368),曼尼托巴大学校长Ernest Sirluck先生旧藏,于加拿大沃丁顿拍卖售出,2023年9约28日,拍品编号41,售价$96,750加币

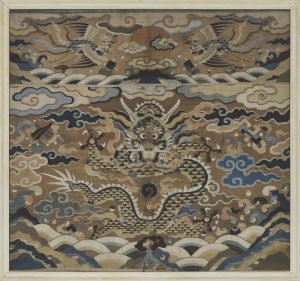

Continuing on to the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), the five-clawed dragons remained strictly reserved for imperial use. The emperor employed the dragon to embody various aspects of his personality and reign, reinforcing his divine connection to the celestial realm. Dragons with a lesser number of claws were subsequently not assigned to the emperor himself, but still associated with the imperial court. For example, this silk embroidered textile depicting a four-clawed dragon was likely used for an altar table (Image 7), possibly for a personal shrine or dedicated room within a household for religious purposes. Such altar fronts were often presented as gifts from the court to noble families, or offered as tributes to temples patronized by the court. In contrast, this yellow-ground silk robe embroidered with a five-clawed dragon from the Beijing Palace Museum would have been worn by the emperor himself (Image 8).

明朝时期(1368-1644)继承了元代政权规定的关于龙的形制的严格要求。皇帝将龙用来强化其“天子”的神圣及绝权威身份以巩固统治。“五爪龙”仍被严格规定为帝王专用,爪数较少的龙依然只能为皇亲国戚所用,其他王公大臣一律不准僭越。例如,下图这张缂丝满金地“云龙戏珠”纹桌围中央描绘了一条正脸四爪龙,腾空凌驾于海水江崖之上,祥云之中。这张缂丝刺绣得到作用可能为供桌桌帷,或用于小型祠堂等。此类供桌装饰物,或常作为礼物被皇帝赠予皇亲国戚使用,或用于皇室供养的寺庙中。相比之下,北京故宫博物院所藏的这件明黄色云龙缎补洒线绣百花撵龙纹袍料则为皇帝本人所穿龙袍专用料 (图8)。

图7,缂丝满金地“云龙戏珠”纹桌围 明 十七世纪,加拿大沃丁顿拍卖2023年12约7日售出

图8,明黄色云龙缎补洒线绣百花撵龙纹袍料 明 万历 (1572-1620),北京故宫博物院,藏品编号故00029411.

Even stricter and more complex systems were adopted following the Manchu-led Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), such as those imposed on ceramics. For example, porcelain wares brandishing yellow glazes and patterns of dragons were reserved for exclusive use by the royal family. The Emperor was the sole user of dragon-patterned porcelain entirely decorated in yellow. The Emperor, Empress Dowager, and Empress used ceramics that were sumptuously glazed with yellow both inside and outside. By contrast, Imperial Noble Consorts, who were second to the Empress, used ceramics with yellow glaze on the exterior but with white glaze on the interior. Further down the hierarchy, the Imperial Concubines used porcelain of yellow ground decorated with green dragons, then regular concubines used blue-ground porcelain with yellow dragons. The following rank used green-ground porcelain with purple dragons, and even further down had green-ground porcelain with red dragons. Illustrated below is an example of a dragon plate used by Imperial Concubines during the Kangxi period (1662-1722), sold at Waddington’s Toronto in June 2023.

满族领导下的清朝(1644-1911年)采取了更加严格和复杂的制度。例如依据官窑瓷器制度规定,釉面为黄色并带有龙纹的瓷器只供皇室专用。具体如下:里外黄釉龙纹器为皇帝所用;皇帝、皇太后、皇后用里外黄釉器;贵妃用外黄内白器;贵妃用黄地绿龙器;嫔妃用蓝地黄龙器;贵人用绿地紫龙器;常在用绿地红龙器。图8为一件清康熙时期(1662-1722年)贵妃所用黄地斗彩云龙戏珠纹盘,于2023年6月售于加拿大沃丁顿拍卖。

图8,清 康熙 罕见黄地斗彩云龙戏珠纹盘 双圈六字楷书款,加拿大沃丁顿拍卖2023年6约29日,拍品编号222.

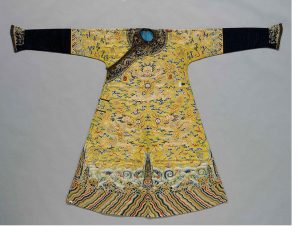

Another strictly regulated system of imperial articles was the imperial dress code. The colour “Minghuang”, or bright yellow, was reserved for the Emperor and Empress Dowager, the Empress, and first rank consorts during formal occasions. An example of such a robe is this bright yellow-ground semi-formal twelve-symbol dragon robe (jifu) from the Royal Ontario Museum Collection. This garment was worn by the Emperor during significant festivals, banquets, and ritual performances. The “jifu” robe held a status second only to a robe worn during formal ceremonial occasions.

另一个制度严明的系统为清朝的宫廷服饰制度,比历代各朝都更为复杂,规定详细且繁琐,阶级分明。皇帝、贵族乃至朝臣的服饰穿戴都有明显的差别,以示尊卑。乾隆皇帝于1748年颁布全面制定朝祭服装配饰的敕令,历时十年,于1759年编纂成《钦定皇朝礼器图式》。其中规定明黄色为皇帝所用,以及皇太后、皇后和正一品妃子在正式场合穿着才可使用。 例图9,现藏于加拿大皇家安大略博物馆的一件明黄地十二章吉服,便为皇帝在重大吉庆节日、筵宴以及祭祀主体活动的前后阶段所穿服饰。吉服在礼制功能上等级规格仅次于礼服。

图9,明黄地龙袍(吉服) 清 乾隆时期 (1735-1795) 约1759年,皇家安大略博物馆,藏品编号 909.12.2.

“Jinhuang” (golden yellow), “Xinghuang” (apricot yellow), “Xiangse” (yellow with a greenish tinge), and “Qiuxiangse” (brown/plum) were worn by imperial family members of varying levels. Lower ranking nobles wore blue-ground robes.

另皇亲宗室可着金黄,杏黄,香色,秋香色;石青(蓝)色则为较低等级服饰。

In regards to the dragons depictions themselves, dragons with five claws referred to as “long” were used exclusively for the robes and badges of the emperor. The next tier were five-clawed dragons called “mang”, and were assigned to the emperor’s sons, first-rank princes and their sons, and second-rank princes. The four-clawed “mang” dragons were assigned to the emperor’s grandsons, great-grandsons, and great-great grandsons, as well as princes from the third down to the seventh rank. Although eight and ninth rank nobles, along with court officials, did not wear dragon badges, their robes were still decorated with five-clawed “mang” dragons.

就龙的表现形式而言,五爪龙纹只用于皇帝所穿的袍服和纹章。五爪蟒纹与龙纹在外观上相似,只是名称有所不同,用于皇子、亲王、亲王世子和郡王服饰中。四爪蟒纹则用于皇孙、皇曾孙、皇太孙以及三品亲王至七品侯伯。尽管八等和九等贵族以及朝廷官员不戴龙徽,但他们的袍服仍装饰有五爪“蟒”龙。

图11,紫地盘金绣龙袍 光绪时期 (1875-1908),售于加拿大沃丁顿拍卖2024年4月11日,第99号拍品

This dragon robe pictured here depicts a five-clawed dragon. It is embroidered with gold thread, which is created by kneading and rolling gold leaf into thin strips, and then intertwining the gold with silk thread to create a malleable and weavable material. This technique was developed as a method of emphasizing luxury and beauty, showcasing the wearer’s prestige and status. The purple ground is certainly a unique colour reserved for kinsmen of the emperor.

图11所示的这件“五爪龙袍”,周身九条龙及锦地均以金线刺绣而成。“盘金绣”技法是通过将金块锤打成金箔,将金箔裁成细条,包裹丝线捻搓,再将金线钉于丝线上绣成龙纹而成。其工艺精美繁复、不惜工本,重点在于展示富丽耀眼的美感和气势,紫地更突显穿着者的尊贵身份。

From ancient times, the respect and reverence for dragons have been evident across various domains of literature, art, and architecture. The depiction of dragons has transformed over thousands of years of Chinese history, from its initial origins as symbols used in rituals and worship, to symbols of wealth and authority. In tandem with China’s unification and rise, its symbolism later became inseparable from imperial authority and the aspirations of the ruling elite. Today, the dragon has become a core attribute of Chinese civilization–an embodiment of people’s hopes and aspirations for a better future, all while upholding traditional cultural heritage.

自古以来,人们对龙的尊崇在文学、艺术和建筑等领域都有所体现。龙的描绘在中国数千年的历史中不停演变,随着中国的统一和崛起,龙的象征意义从最初作为神权的代表,逐渐成为王权地位及财富的象征。如今,龙以然成为中华文明的象征之一,寄托了人们对美好生活的向往和祈愿。

Related News

Meet the Specialist

Amelia Zhu

Senior Specialist / Business Development