Indian sculpture uniquely captures the beliefs and aesthetics of a complex civilization spread out across the subcontinent and beyond – so rich, that this blog should be considered but a brief introduction. Stylistically, the art form is wildly diverse, ranging from naturalistic to abstract, with many of the best examples combining the two modes in a single piece.

Overlapping religious styles

When looking at Indian sculpture, it is important not to look at Hindu, Buddhist and/or Jainist art individually – as many of the aesthetic conventions and ideological aims overlap greatly. These major religions, despite their differences, share similar worldviews. Pratapaditya Pal, curator of Indian and Islamic Art at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, describes them as being “different branches spreading from the same trunk. Hinduism does not differ from Buddhism in the same way that it differs from Christianity or Islam; rather the difference is comparable to that between the Roman Catholic Church and Protestantism.”[1]

A regional and temporal expression

Though serving a religious function, Indian sculpture is best understood as being tied to regional and temporal styles. Pramod Chandra, writing for The National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, suggests that: “whether architect, sculptor, or painter, the same Indian artist created works for patrons of any religious persuasion. Although concessions were made to appropriate iconography and ritual need, from an artistic point of view, no stylistic distinctions can be discerned, except those resulting from the date and place of execution.”[2] He notes that when it comes to many figural expressions, only an expert would be able to distinguish between a sculpture of a Buddhist and a Brahmanical god.

A path to heaven

Pal divides Indian sculpture into two main categories: those intended as icons for worship and contemplation, and those which served more decorative purposes, such as architectural embellishments for temples. Indian artmaking is regarded as a sacred vocation, and both Hindu and Buddhist texts refer to the making of images as a path to heaven.

Per Alice Boner, in her detailed book Principles of Composition in Hindu Sculpture, “the primary purpose of sacred images is not to give aesthetic enjoyment, but to serve as focussing points for the spirit. Born in meditation and inner visualization, they should–and that is their ultimate intent–lead back to meditation and to the comprehension of that transcendent Reality from which they were born. As a reflection of divine Essence they are as doors between the finite and the infinite, through which the devotee may pass from one into the other. If they are beautiful, it is because they are true.”[3]

Price Realised: $5,100

Proportions and Repetition

Indian sculpture – and Indian art – is highly focussed on specific proportions. Many texts are devoted to theories and rules on the subject, and encourage a high degree of fidelity to an ultimate canon. It was believed that gods would not enter sculptures that fell short of these proportional ideals.

As objects of worship, religious sculpture needed to cleave to specific ideological and iconographic conventions. This has resulted in a high degree of stylistic repetition: consider that compositions dating back to the seventh century continue to be produced today with little variation. Indian artists often worked from memory, having memorized the classic forms during their apprenticeship. As Pal notes, “Indian art shares with medieval European art a disregard for the “particular” and a belief in the “universal.” The patterns handed down by tradition were held valid and the concern of the artist was with the ideal rather than with the accidents of nature.”[4]

Pal explains that Indian artists looked to nature, to the regularity of form found in their surroundings, rather than to a physically perfect human, as the ancient Greeks did with their statuary. They focused on a universal ideal, instead borrowing shapes from organic forms including eggs and flower blossoms, and harmonizing those aesthetics with the human body in art.

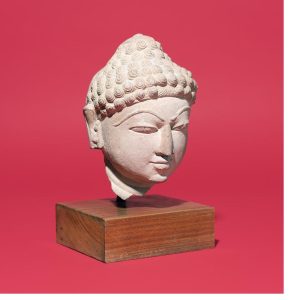

Jina and Buddha

The term “Jina” translates to “the victorious one,” and is the root word of the religion of Jainism. A Jina is an enlightened being, and is analogous to Buddha for the Buddhists. Visually, there is a strong similarity between the two, with both exhibiting short curls and a cranial bump on top of their head. However, the coil of hair between the eyebrows (known as an urna) which characterizes images of a Buddha is omitted from depictions of a Jina. Both Buddhas and Jinas are meant to represent an idealized face, one untethered from human imperfections.

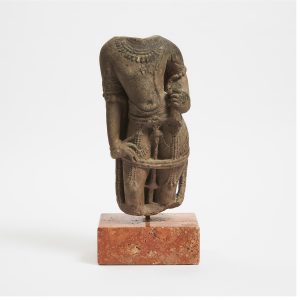

Bodhisattvas

The Buddha’s teachings inspired an incredibly diverse range of sects, each with their own unique interpretations of his message, which became infused with local beliefs as the religion spread out across regions as diverse as India, Asia, China, Tibet, Korea, Japan and southeast Asia. Unsurprisingly, art followed suit, with a wide range of concepts and forms–often untethered from the teachings of the Buddha himself.

Some Buddhist sects deified the Buddha, ushering in the idea of a “Bodhisattva.” A Bodhisattva is a being on their way to achieving Buddhahood who has delayed their ascension to Nirvana in order to help those who are unenlightened and suffering. This being could be either mythical or real. Pal notes that this “opened the door for the introduction of gods and goddesses as saviours of mankind and the elaboration of the pantheon.” This in turn helped make Buddhism more palatable to a diverse populace, better integrating it into Indian society.

About the Auction

Online from August 20-25, this seasonal auction features a large selection of late Qing and Republican period porcelain, jade carvings, embroideries, and cloisonné, as well as more of the collection originally from the Chedington-on-the-Lake Estate. Other categories include South Asian stone carvings, Japanese contemporary prints, and much more. We invite you to browse the gallery.

Please contact us for more information.

Footnotes:

[1] Pratapaditya Pal. Indo-Asian Art From The John Gilmore Ford Collection (Baltimore: The Walters Art Gallery, 1971), 9.

[2] Pramod Chandra. The Sculpture of India: 3000 BC-1300 AD. (Washington: National Gallery of Art, 1985), 20.

[3] Alice Boner. Principles of Composition in Hindu Sculpture: Cave Temple Period, (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1962), 17.

[4] Pal, 13.

Related News

Meet the Specialists

Austin Yuen

Specialist

Amelia Zhu

Senior Specialist / Business Development