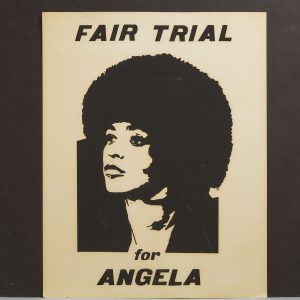

FAIR TRIAL for ANGELA. Four words, not only challenging the validity of a historically biased judiciary system but also calling on the collective power of the people to stand up and fight back against systemic racial, socioeconomic and political injustice. The seminal trial to which this placard refers saw an unprecedented global effort by the public, politicians, artists and scholars to free Angela Davis. It also marked a significant turning point in her journey as a political activist.

To understand what brought Davis to stand trial, one must understand the events that predated her arrival at that moment. Growing up in Birmingham, Alabama during the 40s, 50s and 60s, she experienced firsthand the discrimination that threatened the lives and livelihoods of Black people. Her enclave, nicknamed “Dynamite Hill,” saw over 501 bombings carried out in the name of white supremacy during her time there. The Ku Klux Klan, spanning more than 3 million members nationwide, had successfully infiltrated law enforcement and marched consistently through large cities and small towns, instilling fear and terror in Black communities.2

Lynchings of Black men, women and children were terrifyingly common,3 and segregation laws in the South prevented Blacks from attending the same schools or frequenting the same movie theatres, eating establishments and restrooms as whites. To be Black was to be considered less than human and live in a constant state of fight or flight amid crippling inequality.4

Though Davis left Alabama before the height of the Civil Rights movement to attend school in Massachusetts, Frankfurt and Berlin, she was well aware of the ongoing fight for equality in the South. In the late 1960s, feeling the need to be more involved with the struggle in America, Davis returned home, joining the Black Panthers and the Che-Lumumba Club, an all-Black branch of the Communist Party. Both organizations aimed to restore dignity to Black families living in depression-level conditions, trapped by a system that placed them squarely at the bottom of the employment hierarchy. They organized educational programs, community meals and peaceful protests calling for an end to police brutality, better housing and racial equality.5

In 1969, the University of California at Los Angeles hired Davis as an assistant professor of philosophy to great acclaim. Her first lecture drew over 1,000 people. But almost as quickly as she ascended to popularity, she was dismissed by the UCLA regents, headed by then California governor Ronald Reagan, after a leak identified her as a member of the Communist party.6 At the time, the US government faced increasing backlash amid the escalating Civil Rights and anti-Vietnam war movements and the recent brazen assassinations of Martin Luther King, Malcolm X and Robert Kennedy.

There remained a McCarthy-esque belief that anyone sympathetic to the tenants of Communism was not only an enemy of the state but a threat to the validity of a capitalist system that favoured white elites. Academics such as Marvin X and Saul Castro were just two of many who found their careers conspicuously threatened due to their support of political movements championing Black and brown people.

Considered radical in their views, academics of colour shed light on the fact that Black and brown students routinely faced streaming in high school, encouraging them to seek vocational training rather than higher education. This practice by guidance counsellors meant the ratio of white students to students of colour in universities was shamefully disproportionate. Scholars such as Davis also illuminated that institutions, such as UCLA, were inherently political in their receipt of funding benefiting the government’s presence in the Vietnam war, making their persecution of Black and brown scholars for political reasons hypocritical at best.7

Davis would later say of the campaign leading to her dismissal:

“Education should not mould the mind according to a prefabricated architectural plan. It should rather liberate the mind. It should liberate the mind from established definitions and plans…I maintain that political opinions should be brought into the classroom…I think that education itself is inherently political. Its goal ought to be political. It ought to create human beings who possess a genuine concern for their fellow human beings and who will use the knowledge they acquire in order to conquer nature. But in order to conquer nature for the purpose of freeing man, of freeing man from enslaving necessities.”7

With momentum growing in her favour, Davis amplified her objection to the oppression of civil and human rights by the US government. She was eventually reinstated to her teaching position by the court, which cited that the university could not fire an employee and infringe on their right to free speech due to their political beliefs. Nonetheless, the regents persisted, moving to dismiss her again, this time successfully, citing her speeches as ‘unprofessional’ conduct. The firestorm of attention Davis received from these proceedings, as an outspoken Black ‘radical’ with leftist political and feminist leanings, made her a prime target for white supremacists and the US government.

Following her dismissal, Davis’ notoriety as an activist and advocate for prison reform, racial injustice and free speech grew. She became involved in the case of the Soledad Brothers. Fleeta Drumgo, John Clutchette and George Jackson were three Black prisoners accused and later acquitted of the murder of a guard during a prison riot. A strong supporter of their plight, Davis and others formed the Soledad Brothers Defense Committee, attempting to free the group.8 But, things took a devastating turn when George Jackson’s brother, Jonathan Jackson, orchestrated the botched hijacking of Superior Court Judge Harold Haley, as well as a prosecutor and three jurors in order to negotiate the release of his brother. In the ensuing firefight, both the judge and Jackson lost their lives.5,9

Though there was no evidence placing Davis at the scene, her work on the defense committee and the finding that guns used in the crime were registered in her name, implicated her. Authorities made little mention that due to her receipt of death threats while at UCLA, Davis travelled with full-time security and purchased guns for protection. Jonathan Jackson was also a member of her security detail at the time of the hijacking.10

The ensuing manhunt was one of the most exhaustive in American history, with Davis added to the FBI’s ‘Ten Most Wanted’ Fugitive List and her picture posted in all forms of media from coast to coast. She was only the third woman to be added to this list known for hardened murderers, sociopaths and serial killers. In response, the FBI, independent mercenaries and local police forces mounted an extensive campaign for her capture, rounding up Black women across America with an afro or gap between their teeth.11

On October 13, 1970, agents captured Davis in New York City. She faced the charges of first-degree murder, kidnapping and conspiracy, all charges carrying the death penalty. The prosecution’s weak case against her confirmed that the trial was not about her guilt but her iconic status as a revolutionary, not only within the Black but the global community.11 By February 1971, more than 200 committees in the United States, including Black People in Defense of Angela Davis, and 67 in foreign countries, worked tirelessly to free Davis from prison. Songs by John Lennon and Yoko Ono, The Rolling Stones and Nina Simone became the soundtracks of resistance, while poets, writers and scholars penned essays and delivered speeches in her name.12

As fate would have it, before her trial began, the California Supreme Court abolished the death penalty allowing Davis’ legal team to submit a motion for bail. The ruling was a pivotal moment in the trial as it meant that if Davis secured bail, she would walk into the courtroom as a peer rather than in shackles – a psychological implication of guilt that damned many Black prisoners before her. Right after the decision, protestors took to the streets placards in hand and thousands of telegrams, letters, petitions, and phone calls came in from all over the country and the world demanding Davis’ release.13

The onslaught of support was so overwhelming that Richard E. Arnason, the judge on the case, noted at the bail hearing that he received more telegrams than he could read and granted her bail. In Davis’ mind, the efforts of the people had an impact on the judge’s decision to release her. In a 1972 interview with Black Journal, she stated, “What it meant was that the judge could release me on bail knowing that there existed a climate of public opinion which would agree with that and he wouldn’t feel isolated.”

After 18 months of imprisonment, including long periods in solitary confinement, Davis was acquitted of all charges. The experience cemented her dedication to the fight for others still trapped in the school-to-prison pipeline. It was a system in which a disproportionate number of minors from disadvantaged backgrounds, such as the Soledad Brothers, became incarcerated on misdemeanours only to find themselves imprisoned for decades or even life.13

The statement on this placard, Fair Trial for Angela, extends far beyond Davis’ fateful trial. Given recent events, including the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and so many others, it is a call to action for the ongoing support of those facing racial, political and gender violence. It is also a rallying cry for many others still trapped in the prison pipeline system for their beliefs, skin colour or socioeconomic circumstances. This placard is a vital part of our history, reminding us that our collective voices can enact powerful change when we band together to fight injustice.

Ingrid Jones is an independent curator, creative director and multidisciplinary artist based in Toronto whose practice engages topics of marginalization, memory and intersectionality. She has received grants, awards, and recognition from the Ontario Arts Council, Canada Council for the Arts, The Design Exchange and The Toronto Short Film Festival and received invitations to lecture on best practices in photography at Ryerson University and Sheridan College. Her lens-based and design works are featured in Computer Arts UK, Vice Berlin, Stack Printout, The Huffington Post, National Geographic, Globe Style, and Fotografie. Ingrid’s exhibition, Nostalgia Interrupted, focused on the framing of nostalgia for Black, Indigenous, and racialized communities, will take place in 2022 at Koffler Centre for the Arts.

Bibliography:

- Eskew, Glenn T. (1997). “Bombingham”. But for Birmingham: The Local and National Movements in the Civil Rights Struggle. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9780807846674.

- Mockaitis, Tom. “White Supremacy and American Policing.” The Hill, The Hill, 6 Feb. 2021, thehill.com/opinion/national-security/537611-white-supremacy-and-american-policing

- NAACP. “History of Lynching in America.” NAACP, 9 May 2021, naacp.org/find-resources/history-explained/history-lynching-america.

- Editors, History.com. “Jim Crow Laws.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 28 Feb. 2018, www.history.com/topics/early-20th-century-us/jim-crow-laws

- Lewis, Jone Johnson. “Biography of Angela Davis, Political Activist and Academic.” ThoughtCo, Feb. 16, 2021, thoughtco.com/angela-davis-biography-3528285

- “Academic Freedom: The Case of Angela the Red.” Time, Time Inc., 17 Oct. 1969, content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,840245-1,00.html.

- UCLACommStudies, director. Angela Davis Speaking at UCLA 10/8/1969. YouTube, YouTube, 17 Mar. 2014, www.youtube.com/watch?v=AxCqTEMgZUc.

- Tanebaum, Julia, et al. “The Soledad Brothers.” Rebel Archives in the Golden Gulag, rebelarchives.humspace.ucla.edu/exhibits/show/rebel-archives/the-soledad-brothers.

- Media, American Public. “American RadioWorks – Say It Plain, Say It Loud.” APM Reports – Investigations and Documentaries from American Public Media, American Public Media, americanradioworks.publicradio.org/features/blackspeech/adavis.html.

- Bhavnani, Kum-Kum, and Angela Y. Davis. “Complexity, Activism, Optimism: An Interview with Angela Y. Davis.” Feminist Review, no. 31, 1989, pp. 66–81. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1395091. Accessed 19 June 2021.

- Charlton, Linda. The New York Times, The New York Times, 1988, archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/books/98/03/08/home/davis-fbi.html.

- Roman, Meredith L. “‘Armed and Dangerous: The Criminalization of Angela Davis and the Cold War Myth of America’s Innocence.” Women, Gender, and Families of Color, vol. 8, no. 1, 2020, p. 87., doi:10.5406/womgenfamcol.8.1.0087.

- Lynch, Shola, director. Free Angela and All Political Prisoners., 2012, sholalynch.com/free-angela-2013/.