Lot 47

OSCAR CAHÉN

Provenance:

Private Collection, Toronto

Note:

Oscar Cahén is acknowledged as one of the principal contributors to the evolution of abstract art in Canada in the 1950s. A prominent, influential member of Painters Eleven, his achievements have been in the public light on near perpetual exhibition in important public art institutions for the past 60 years. Thus, we may have come to imagine that we know what a characteristic picture is by Oscar Cahén. Many continue to celebrate the artist as an unparalleled colourist. Thereby, an exemplary Cahén painting, it seems, displays his remarkable mix of chromatic pyrotechnics, astonishing clashes of magenta, reds, oranges with striking complementary colour accents of vibrant blues and green. While these commendable signature attributes define certain outstanding Cahén paintings they are also surprisingly atypical of the characteristics of the vast majority of Cahén works.

His mature career as an aspiring, progressive artist was all too brief, ten years bracketed between 1947 and his death in an auto accident in 1956. Throughout this period Cahén was a restless spirit, experimenting and exploring a wide range of aesthetic options, themes, approaches, media and timbres. A good number of his works are black and white or near monochrome. Why should this surprise? Cahén was one of Canada’s most respected illustrators, designing countless magazine covers for leading publications such as Maclean’s, creating drawings to accompany literary texts and more. He was a key member and annual exhibitor with the Canadian Society of Painters in Water Colour and The Canadian Society of Graphic Arts. Thereby, Cahén exercised his craft daily. He was fluid and at total ease creating and composing upon paper, perhaps even more so than upon canvas. His graphic acumen may have exceeded his considerable colouristic flair.

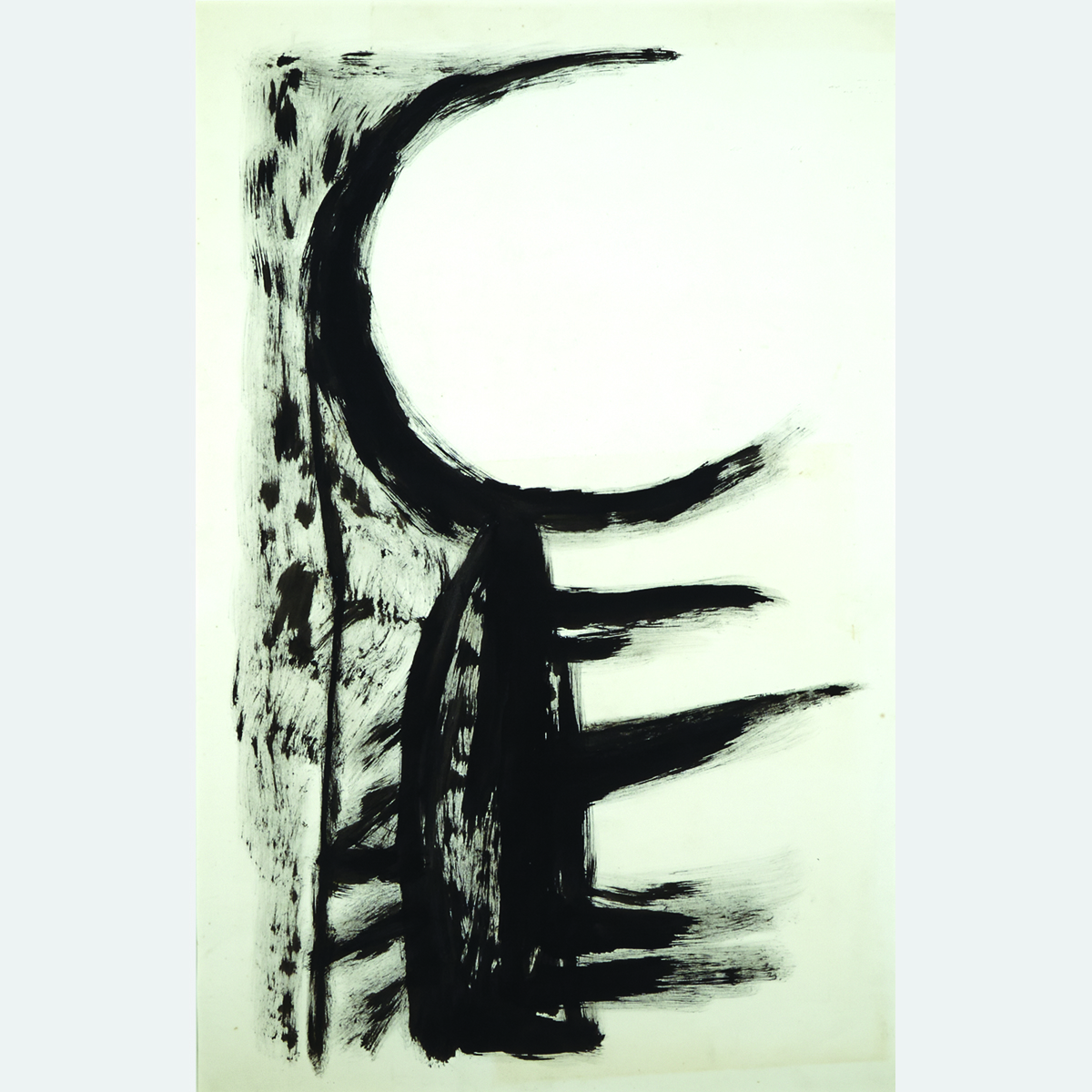

This lot is a considerable achievement, a balance of expressive abandon and restraint, blunt gestural barrage and withheld, tempered delicacy. Cahén it seems was vexed by the idea of creating a composition that juggled polar opposites. In this work the left half of the picture is fully engaged, forceful black lines atop scumbled background. The right hand side of the page is poignantly blank, pristine, untouched. It is a challenge that he will battle the rest of his career, however, perhaps never so elementarily as in this picture on paper in strident black and white.

The powerful mark-making of Franz Kline may seem the evident place to start when unravelling the evolution of Cahén’s black and white pictures such as this one. However, this is just not satisfactory. Cahén’s central image seems bidden by some referent, we do not know precisely what: a head, a trunk, outreaching appendages? Nevertheless it is a figure against a ground. His work embraced vegetative themes, flowers, pods; it quoted clawed roosters and chess pieces. Is the dominant void circle a celestial orb or a thought bubble? Many of his illustration and art works of the period were absorbed by technology, the appearance of traffic and railroad crossing lights. How is it that it is simultaneously all of these and none of these?

The abstracted surrealism of Picasso, Gonzales, David Smith, Max Ernst and the Latin tradition including Tamayo all beg for discussion within the company of this picture. Perhaps, the evident touchstone is British artist, Graham Sutherland. His works depicting abstracted processional “personages” were in exhibition, publication and major museum collections at this period, including Toronto and the Art Gallery of Toronto.

Cahén has been lauded historically for his exemplary chromatic inventiveness, Untitled, demonstrates why his Painters Eleven compatriots so revered his talent. It is a terse work, that stands beside the achievements of Borduas and Les Automatistes, Soulages and the finest of second generation abstract expressionism.

This work was executed circa 1952-1954.

We thank Jeffrey Spalding C.M., R.C.A. for this essay.