What do many of the finest wines and spirits in the world have in common? Oak!

What do many of the finest wines and spirits in the world have in common? Oak!

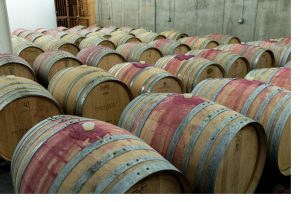

Oak has been used in the making of wine and spirits for centuries. Oak wood is both hard yet pliable, making it ideal for barrels. Before glass bottles entered mainstream use in the 1600s, alcohol was typically stored and transported in wooden barrels— which has influenced production methods and added flavour profiles ever since.

Using oak is an expensive proposition. One oak tree only yields two standard 220 L (64 gal) barrels, and trees take decades to reach a usable size. Proper barrel making (coopering) must be done without the use of glue and is a highly skilled trade. New French oak barrels, considered to be the best of the best, cost around $900 on average but can reach upwards of $3000 USD each. American oak barrels are slightly less expensive, costing approximately $600 per unit. These expenses impact the final price for the consumer, adding an additional $2-$4 in raw material cost per bottle.

So why use oak at all?

Flavour

Oak adds flavour, changing the character of the liquid it holds. The more contact with wood, the more pronounced the flavours of the final product. Size matters: the smaller the barrel, the more contact with oak. Age matters too: the newer the barrel, the more prominent the oak’s flavours will be.

Skilled coopers are integral to the success of a vineyard or distillery. When preparing a new barrel, coopers burn or “toast” the inside using an open flame or a hand-held torch. This has the effect of “caramelizing” the natural sugars present in the wood, and enhances the oak’s natural flavours of caramel, butter and vanilla. Toasting can be light, medium or heavy, as determined by the vintner or distiller. The heavier the toast, the stronger the flavours. The carbon in the burned layer also acts as a natural filter, removing impurities including sulphur compounds, which affect the way the wine or spirit tastes.

Oak’s toasty flavours soften and fade the more a barrel is used—similar to reusing a teabag. These “used” barrels are referred to as “neutral oak,” meaning that those bold essences are no longer imparted to wine. Winemakers and distillers choose how long their products sit in oak, and vary from product to product. For example, a winemaker might use older oak barrels in a vintage to allow delicate varietals to shine, unmasked by the oak, or even use a combination of old and new barrels in a single cuvée. Typically, a winemaker keeps their barrels for around five years, before selling them to distilleries for use in the production of Scotch and whisky.

Types of oak barrels

Distillers use casks for much longer than winemakers. A single malt Scotch is usually aged in wood anywhere from three to forty years, even as much as 50 years, while a single cask might be used and re-used for up to 70 years. Many distilleries prefer to use barrels that have already been used to age spirits or wines like bourbon or sherry, as the flavour of a new oak barrel can often be too powerful for long-term maturation. Using ex-bourbon casks helps whisky become sweeter and creamier, while ex-sherry casks add nutty and fruity flavours to whiskies like Macallan. Distilleries may even lend new casks to producers of Sherry, Port and Sauternes in order to better season them. Alan Winchester, Master Distiller for The Glenlivet, notes that oak casks are one of a distiller’s most powerful tools, with 60-80% of the rich flavours of the whisky coming directly from the wood. Distillers build flavour, aroma, colour and texture through maturation by choosing which casks to use and for how long. Whisky Advocate explains that “without time in oak barrels, whisky would remain white and fiery, devoid of the toasty, caramel, nutty, or vanilla notes that make our mouths water. It’s simple—without oak, there is no whisky as we know it today.”

Like the other ingredients used to make wine and spirits (e.g. grapes, grain, etc.), the type of oak used will also influence the final product. Oak comes from the Quercus genus, which includes over 600 species of oak. Two particular species are preferred: American white oak (Quercus alba) and European white oak (Quercus petrea), which each have a unique structure, density and flavour. The former is noted for its subtle, woody and spicy notes of clove and cedar, while the latter is prized for its more robust flavours, including creamy elements of coconut and cinnamon. Even the climate where the oak tree was grown can modify the flavour of the barrels—wood from France is very different from wood grown in Hungary.

Another benefit to using oak barrels is the impact of oxygen. Oak is porous, allowing a slow seep of oxygen. This softens the product within, making it smoother and less bitter. In winemaking, this also facilitates malolactic fermentation—when the tart-tasting malic acid found in grape must is converted to creamier-tasting lactic acid. Oxygen is crucial for the construction of a great red wine, impacting its colour, aging potential and tannin structure.

Structure

Oak wood has natural tannins. Tannins are an astringent, bitter-tasting substance found in wood, bark and other plant tissues including the skin, seeds and stems of grapes both red and white. The puckery, dry or itchy feeling that is felt in the mouth when drinking red wine or a cup of overly-steeped tea comes from tannins.

The tannins found in oak leach into wine during the aging process. Tannins help provide structure, balance, and texture to wine, while also allowing it to age properly. Red wine is where tannins are most noticeable, though some white wines that are aged in barrels or skin-fermented show tannic structure as well. Though tannins are found naturally in grapes, oak is the greatest source of tannin in wine.

Tannins also add astringency, or dryness to spirits, while also affecting colour. Similar to wine, tannins help develop flavour and maintain structure during the maturation process. Tannins remove sulphury notes, while infusing spirits like with notes of spice, smoke, and vanilla.

Alternatives to oak barrels

Oak flavours can be added to wine by putting oak chips, or pieces of wood, in to soak during the aging process. In order to keep their costs low, liquid oak extract may be added to inexpensive wines. Different species of trees have also been used to age wine and spirits, including chestnut, acacia, Iberian oak and English oak.

Some modern winemakers view the use of oak as an unnatural additive. Cement, stainless steel, plastic and even clay vessels have emerged as alternatives to oak in modern wine and spirits production. Nowadays, the use of oak is no longer an imperative, but rather a stylistic choice. Without oak, wines are more subtle and pure expressions of their varietals, as the aging vessels impart little flavour of its own. Not using oak makes for a less expensive and less labour-intensive finished product. Similarly, oak can be difficult to employ correctly—many wine drinkers can probably recall the overpowering taste of an overly-oaked wine.

About the auctions

Our next Fine Wine and Fine Spirits auctions will be held online from May 29 – June 6, 2023.

We are now accepting consignments for Fall 2023.

For consignment information please contact us or visit the Fine Wine & Spirits Consignments page for more information.

Related News

Meet the Specialists

Joann Maplesden

Senior Specialist

Devin Hatfield

Specialist