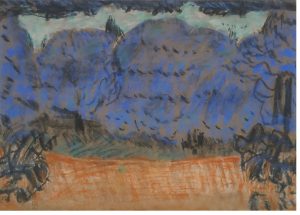

PAYSAGE HARMONIE BLEUE ET ORANGE (DECOR POUR JEUX), CA. 1920-1925. pastel in colours on paper, stamped with the initials “PB”; sheet 7.9 x 11 in — 19.5 x 27 cm. Estimate $12,000-$18,000

Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947) set out not to faithfully record what he saw, but instead to capture his impressions, what he called “a transcription of the adventures of the optic nerve.” Bonnard rarely painted from life, preferring to sketch his subject before working on the painting in the studio. This method allowed his sense of inspiration and memory to supersede reality. Regarded as one of the greatest colourists of modern art, Bonnard would combine hues in unexpected ways.

LES NABIS

Bonnard was a member of an artistic group known as Les Nabis. The movement came about after Paul Gaugin mentored Paul Sérusier in the artist colony and village of Pont-Aven in Brittany. Gauguin was said to have told Sérusier “How do you see this tree? It is green. So put green, the most beautiful green on your palette; and that shadow, especially blue? Don’t be afraid to paint it as blue as possible.” Under his influence, Sérusier painted a landscape on a small wooden panel.

A handful of Sérusier’s peers, many of whom were fellow students at the Académie Julian, viewed the painting as nothing short of a revelation. In 1888, they decided to form a movement around this new aesthetic vision. They would refer to Sérusier’s painting as “The Talisman” and would name themselves Les Nabis, deriving from the Hebrew term for ‘prophet.’ Members included Bonnard, Sérusier, Edouard Vuillard, Félix Vallotton, Maurice Denis and others, totalling a dozen.

The members shared a desire to reject Impressionism’s naturalistic, descriptive tendencies, preferring to focus instead on spiritual and emotional aspects. They believed that art should not be a faithful depiction of nature, but rather an expression of symbols and metaphors created by each individual artist. Gauguin was greatly admired by the Nabis, particularly his Symbolist works. Japonism, then at the height of its popularity in Europe, would also influence the group, as would the decorative arts.

Though their styles varied greatly, the Nabis’ style was characterised by bold blocks of colour. Denis, the group’s chief theorist, produced a manifesto in 1890 titled “Definition of Neo-Traditionalism.” Enclosed within the article was the pronouncement – which is said to prefigure much of the modern art which was to follow: “Remember that a picture — before being a war horse or a nude woman or an anecdote — is essentially a flat surface covered with colours assembled in a certain order.”

EXAMINING THE EVERDAY

After Les Nabis disbanded around 1900, Bonnard spent the ensuing decades in search of artistic expressions. The Met Museum notes that “for Bonnard, the act of painting was an investigation—the investigation of the physical substance of paint, the visual rhymes echoing throughout the canvas, the dialogue of color notes.” This, combined with his fondness for domestic interiors and intimate scenes of daily life, set him apart from the more conceptual art of his contemporaries.

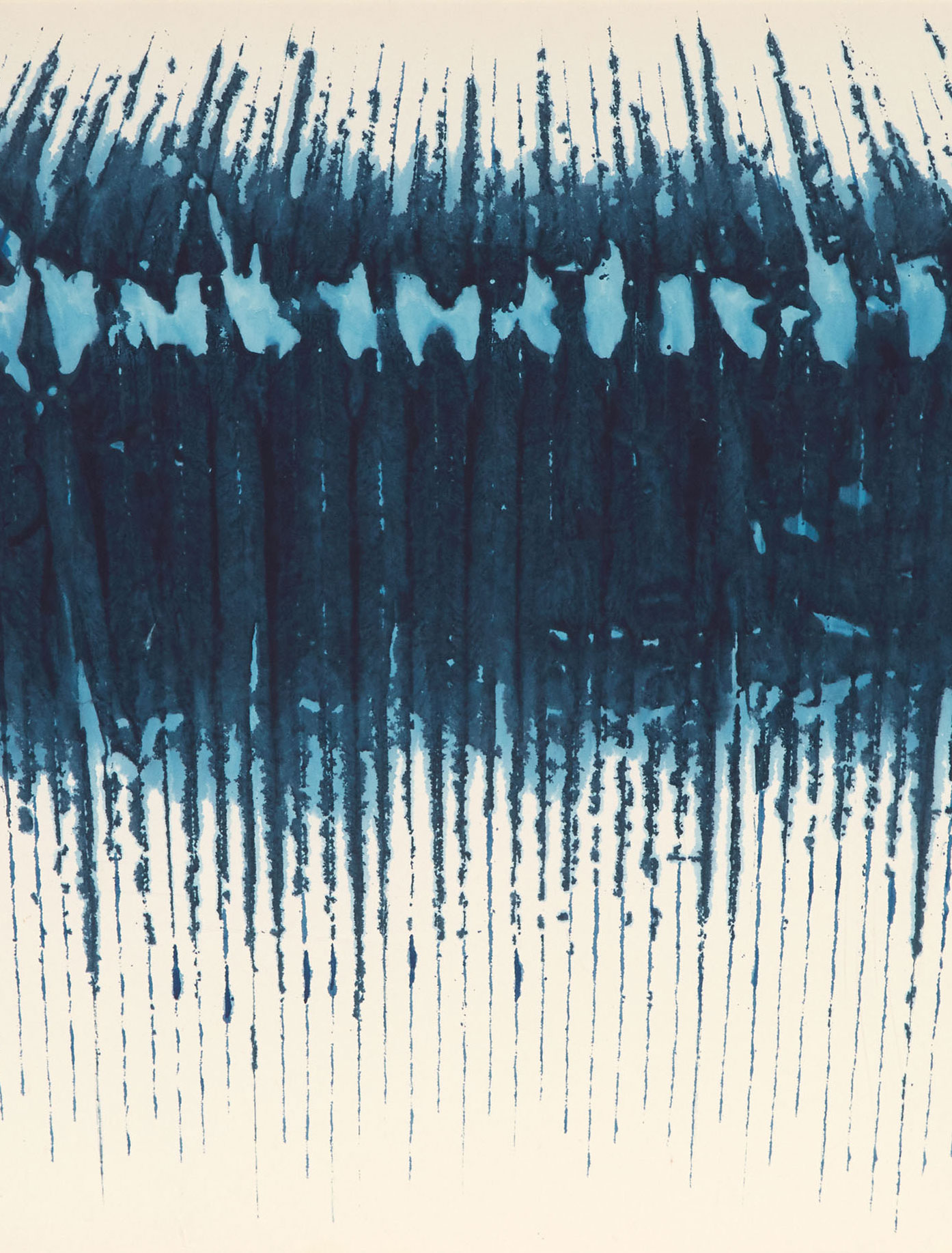

ÉTUDE POUR HARMONIE BLEU ET ORANGE, CA. 1920-1925. pencil on paper, stamped with the initials “PB”; sheet 6.9 x 10.2 in — 17.5 x 26 cm. Estimate $4,000-$6,000

His incredible proficiency with colour would incite Matisse to call Bonnard ‘one of the greatest painters.’ Quoting the Met again, for Bonnard, “color and its color harmonies become the overriding metaphor for the expression of his experience. Color in his late painting transcends descriptive content. In the late masterpieces, color becomes the subject, the vehicle of light, and the means by which we enter the paintings with our eyes. Using hot and cold hues, Bonnard guides the eye, very deliberately, on an adventure through the positive and negative spaces of his complex canvases. One cannot stress enough the importance Bonnard gave to finding the image in paint and to finding the boundaries of his rectangle.”

By 1915, Bonnard felt he had gone too deep into his exploration of colour, at the expense of form. His paintings after this period reflect a new focus on structure, though he never abandoned his interest in strong colour values. He began painting a series of nudes in their baths in the 1920s, which would become one of his most famous themes. By the end of that decade, the subject matter of his work became more or less fixed: still lifes, self-portraits, Saint-Tropez seascapes, and garden views painted from his house at Le Cannet, near Cannes, where he had relocated in 1925 with his wife and model, Maria Boursin (also known as Marthe de Méligny). Boursin would be central in both Bonnard’s art and life, posing for him for nearly 50 years, from their meeting in 1893 until her death in 1942. Their house in Le Cannet – nicknamed Le Bosquet (The Grove) – would provide the subject for some of Bonnard’s most recognizable paintings

The familiar rooms, objects, models and rituals of daily life in Bonnard’s work were integral to his process. The artist acknowledged his need to paint the familiar: when asked if he could add a new object to his narrow still life repertoire, he explained that he could not, because “I haven’t lived with that long enough to paint it.” The same went for all of Bonnard’s subjects, be they human or environmental. The root of this peculiarity lay in Bonnard’s process: though he painted rooms in his own house, populated by his own wife, he began his work by making small drawings and watercolours, which he would develop slowly over time. Scenes needed to be etched in his memory before he could paint them, for it was never the thing itself that he sought to paint but rather the memory of it.

As a result of this process, dating Bonnard’s work is never perfectly precise. Sketches might serve as the basis for several paintings, on which he would work simultaneously. He would tack up large canvases to the wall of his studio, working on different subjects at the same time. Once paintings were completed, they would be cut out from the larger surface. Often this process took months and even years. Paintings would be constantly reworked, which is why a precise chronology of his pieces evades scholars.

We are pleased to be offering two works from the 1920s by Bonnard in our Modern, Post-War and Contemporary Art auction, online from November 19-24. It is a special occasion when both sketch and painting are united, as is the case for lot 10 and lot 11.

About the auction:

Our inaugural Modern, Post-War and Contemporary Art auction features artworks by a wide range of International artists. Carefully curated for our collectors across Canada and International clientele, this auction highlights important creations such as Baigneuse accroupie, Grand Modèle by Auguste Rodin, Deux Figures by Henri Matisse, and Paysage harmonie bleue et orange (décor pour jeux) by Pierre Bonnard. Also included are works by Dorothea Sharp, Günther Förg, Ray Smith, Alexis Rockman, Gunther Brus, Rosa Bonheur, Joel Meyerowitz, and Cecil Maguire.

The auction will be on view at our Toronto offices, 275 King Street East, 2nd Floor:

Sunday, November 20 from 12:00 pm to 4:00 pm

Monday, November 21 from 10:00 am to 7:00 pm

Tuesday, November 22 from 10:00 am to 5:00 pm

Please contact us for more information.

Related News

Meet the Specialist

Goulven Le Morvan

Director, International Art, Montreal