Despite his great skill and originality as a draughtsman and artist, Dalí was a Spanish Surrealist who had rejected – even mocked – religion in his youth. In contrast, “The Divine Comedy” was a religious narrative poem embraced by the Roman Catholic Church and widely considered to be the greatest work of Italian literature.

So how did this avant-garde provocateur come to illustrate a medieval masterpiece?

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE DIVINE COMEDY

Written circa 1308–21, “The Divine Comedy” is divided into three major sections – Inferno, Purgatoria and Paradiso. Each section of the poem represents the soul’s journey towards the divine, beginning with the acceptance and rejection of sin (Hell), penitence (Purgatory), and finally, revelation and ascent towards God (Heaven). The story follows a pilgrim – assumed to be Dante himself – on Good Friday in the year 1300. Guided by the Roman poet Virgil, who represents the zenith of human knowledge, Dante must descend through nine circles of Hell, where the damned are tormented for eternity. After reaching the bottom, the two men escape and reach the shores of the mountain island of Purgatory. After Dante has climbed through seven terraces, each corresponding to the seven deadly sins, Virgil takes his leave of Dante. Virgil is unable to serve as Dante’s guide any further, for human knowledge cannot explain or comprehend the divine. The final third of Dante’s journey is led by his platonic love, Beatrice, who symbolizes theology. She guides him through nine celestial spheres of Heaven towards the Empyrean, a realm beyond physical existence, where he briefly glimpses the glory of God.

Dante (1265-1321) wrote “The Divine Comedy” after being expelled from Florence in 1302. He penned the work in his native Florentine vernacular dialect instead of in Latin, which was the standard language used for poetry during the Middle Ages. Only the most educated readers were able to read in Latin, meaning that high literature was reserved for but a privileged few. By using a living dialect, Dante allowed a much wider swath of the population to access his work. As such, “The Divine Comedy” is considered to be the first great work of truly Italian literature and laid the foundation for the modern Italian language used today.

The ways in which Dante visualized and described Hell, Purgatory and Heaven have become canonical. His imagery has deeply shaped how these biblical concepts are represented in Western art and literature over the ensuing centuries. Considered as both Dante’s greatest work as well as a masterpiece of world literature, few other pieces of art can be said to have impacted culture on this massive scale.

FROM THE POPE TO PARLIAMENT

Dalí (1904 –1989) was born to a Catholic mother and an Atheist father. The latter’s beliefs won out, and Dalí was sent to be educated in a state-run school. Early work, such as films made with Luis Bunuel, portrayed the church and its acolytes as corrupt and stupid. Dalí blamed the church for his repressed attitudes towards sex. He even went so far as to draw an image of Jesus and the Sacred Heart in 1929 entitled “Sometimes I spit with pleasure on the Portrait of my Mother (The Sacred Heart).”

These feeling of anger towards the Church began to shift as he matured, and Dalí found himself pulled again towards his religious roots. He had married his wife Gala in a church ceremony in 1934, and began incorporating holy themes in his work by the late 1940s. In 1949, he painted “The Madonna of Port Lligat,” which fused his Surrealist ideas with traditional Catholic iconography. The same year, Dalí met with Pope Pius XII to show him this Madonna, and asked for the Pope’s blessing to paint religious works, specifically the Immaculate Conception, to which the Pope consented. Dalí was to remark that the Pope showed great comprehension of the artist’s work, and so devoted himself to painting more surrealistic religious works, including a second “Madonna of Port Lligat.”

In 1950, inspired by this papal blessing, the Italian government, specifically The National Library of Italy, commissioned Dalí to create 100 illustrations for a commemorative edition of Dante’s “The Divine Comedy” to mark the upcoming 700th anniversary of the poet’s birth. Though Dalí’s inimitable style was perfectly suited to the task, some Italians viewed the commissioning of a foreign artist to interpret this quintessentially Italian masterpiece as a crime against the Italian State. Protests became so feverish that they reached the Italian Parliament, who, bowing to pressure, canceled the contract with Dalí.

WATERCOLOUR TO WOODBLOCK

Despite the withdrawal of official patronage, Dalí was undeterred, too enthralled by the project to drop it. Dalí had long been familiar with the text, and his artistic focus during that period was centred on the exploration of classicism and mysticism, which aligned perfectly with the task at hand. Art historians also suggest that Dalí saw a parallel between Dante’s love Beatrice and his own wife and muse Gala, who served as a model for his illustrations of the character

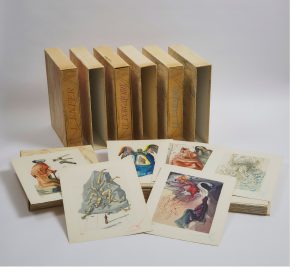

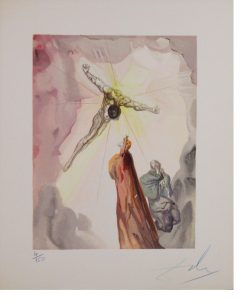

For the project, Dalí produced 100 watercolours between 1950 and 1952, one for each of the verses in “The Divine Comedy,” divided into 34 for Inferno, and 33 each for Purgatoria and Paradiso. His unbridled creativity was at its apex in this project, channeling his proclivities for the bizarre, the sublime and the nightmarish.

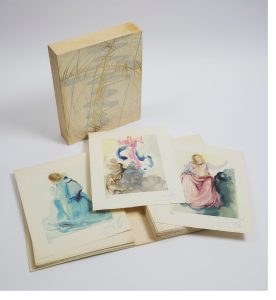

To see the project to completion, Dalí reached out to Joseph Forêt and his Paris-based fine art publishing house Editions d’art Les Heures Claires. Fôret agreed to purchase the entire set of watercolours as well as the rights to publish Dalí’s version of “The Divine Comedy” in limited edition. Each of Dalí’s watercolours was carefully reproduced in woodblock by master engraver Raymond Jacquet and his assistants Jean Taricco and Paul Bassin, a process closely supervised by the Dalí himself.

In order to render the drawings faithfully, each image needed to be “deconstructed” into its component colours. Each colour in a polychromatic print is laid onto its own block: as an example, a print with 10 colours will typically have 10 interdependent woodblocks involved in printing the final image. Dalí’s 100 illustrations necessitated the carving of over 3,500 separate blocks, and took just under five years to complete. This number represents an average of 35 blocks per print — though each print varies in terms of its complexity, some have estimated that the more intricate ones required upwards of 50 blocks to reproduce.

PUBLISHED AT LAST

Dalí’s interpretation of “The Divine Comedy” is considered to be among the most original and expressive bodies of work in the artist’s career, a view supposedly echoed by Dalí himself. In places, the artist’s work depicts Dante’s words with high fidelity, while in others, the motifs are pure Dalí – windowed torsos, limbs on crutches. Writing for a London exhibition of this work in 2021, Luke Wallis writes that:

More than any of the poem’s many illustrators, Dalí fits Dante’s vision. The inferno is to some extent already an absurd, surreal nightmare; in the act of translation from word to image, it is oftentimes difficult to pinpoint where the early Renaissance Poet ends and the Surrealist artist begins. That the two possess a shared sensibility in their conception of hell and purgatory as intellectual torture, body-horror and farce, we might expect. Dalí’s Paradise, however, offers up something we are much less likely to anticipate. The delicacy of line and colour on display here is unique in his oeuvre. All in all, it is something of a revelation.

In May 1960, Dalí’s watercolours went on display at the Museum Galliera in Paris. Les Heures Claires published 150 editions of the prints in 1963, with all the 100 prints signed by Dalí: Inferno in red, Purgatoria in purple, and Paradiso in blue, each numbered 150. Limited edition books were also released, 4765 books in French and 2,900 in Italian. A subsequent edition of 1000, known as the “German edition” was released in 1974 by adding English and German text to previous copies of the French edition, along with block signatures, under the supervision of Dalí.

ABOUT THE AUCTION:

Waddington’s is pleased to be offering a complete set of Dalí’s “The Divine Comedy” woodblock prints in our Editions auction, online from March 25-30, 2023. Other highlights from Canadian, Inuit and international artists include Jack Bush, Alexander Calder, Jim Dine, Tracey Emin, Damien Hirst, Henry Moore, Andy Warhol, David Blackwood, Rita Letendre, Jean-Paul Riopelle, Guido Molinari, Ningeokuluk Teevee and more.

Please contact us for more information.

On View:

Sunday, March 26 from 12:00 pm to 4:00 pm

Monday, March 27 from 10:00 am to 5:00 pm

Tuesday, March 28 from 10:00 am to 5:00 pm

FURTHER READING

https://www.bonhams.com/auctions/18560/lot/63/

https://exhibitions.salvador-dali.org/en/divine-comedy-dante-alighieri-illustrated-salvador-dali/

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TcyDajGnBCI

https://lockportstreetgallery.com/dali/salvador-dali-divine-comedy/

https://www.eamesfineart.com/viewing-room/59-salvador-dali-the-divine-comedy/

Related News

Meet the Specialist

Goulven Le Morvan

Director, International Art, Montreal