“The head of the Dying Alexander at Florence is an archaeological enigma.” – Otfried Mueller

Expressing deep suffering, his eyes tipped upwards to the heavens, the head of the Dying Alexander became one of the most famous marbles of the Renaissance. Inspiring numerous copies, this portrait was imagined to be a definitive image of the famous Macedonian warrior– until it wasn’t.

Waddington’s is pleased to offer a massive 17th century Roman copy of the Dying Alexander in our Cabinet of Curiosities auction, online from March 25-30. To mark the occasion, we’ve traced the story of this famous face from the height of its fame in Florence to what scholars suggest might be its actual origin story.

A FAMOUS PORTRAIT OF ALEXANDER THE GREAT…

The original Greek marble from the late Hellenistic period is held in the Uffizi in Florence, Italy. The attribution of this portrait was due in part to the distinctive leonine mane of hair that is consistent with the iconography of other portraits of Alexander, as well as due to the writings of Plutarch of Chaeronea. Plutarch explained that only Lysippus, a Greek sculptor of the 4th century BC, was allowed to make a portrait of Alexander:

“the outward appearance of Alexander is best represented by the statues of him which Lysippus made, and it was by this artist alone that Alexander himself thought it fit that he should be modelled. For those peculiarities which many of his successors and friends afterwards tried to imitate, namely, the poise of the neck, which was bent slightly to the left, and the melting glance of his eyes, this artist has accurately observed.”

Larger than human size, the first record of the Uffizi bust dates back to 1550. It is listed as a portrait of the dying Alexander in the collection of Cardinal Pio da Carpi in Campo Marzio, Rome. The bust arrived in Florence in 1580, making its way into the Medici collection. It was carefully and extensively restored before being mounted to a plinth engraved ALESSANDRO. Once on display, it quickly became the object of much fascination: it was replicated widely during the 16th and 17th centuries, the source for numerous drawings, paintings and sculptural copies.

…THAT WASN’T A PORTRAIT OF ALEXANDER THE GREAT…

In 1779, a sculpture fragment known as the Portrait Bust of Alexander or Azara Herm was unearthed in Tivoli, which caused archaeologists to doubt that the Uffizi’s Dying Alexander was a portrait of Alexander at all. The Azara version, a 1st century copy of a 4th century sculpture by Lysippus known as Alexander with Spear was much easier to directly attribute to Lysippus himself. Accordingly, scholars then considered the Azara version to be the only definitive portrait of Alexander that had been commissioned by the Macedonian ruler himself. In this version, Lysippus did not idealize Alexander’s features, but sculpts him closest to what he might actually have looked like. The Azara head is now in the collection of the Louvre, in Paris.

The Museum of Classical Archaeology at Cambridge presents the misattribution of the Dying Alexander fragment as “the Renaissance desire to find in ancient sculpture illustrations of ancient history.” The Museum notes that the expression and pose of the Dying Alexander are more dramatic than would be employed in any portrait from the period, which tend to be more stoic in tone.

Alfred Emerson, writing in 1883, blames the misattribution of the Uffizi sculpture on a flight of fancy on the part of the 16th century Florentine restorers, who might have seen only what they were looking to see. He notes that Plutarch’s text clearly states that Lysippus depicted Alexander’s head as tilting to the left, while the head on the Uffizi bust tips to the right.

…BUT MIGHT BE FROM THESE PLACES!

The Uffizi notes that while its version does not depict Alexander himself, it is part of the large group of contemporary works that were inspired by portraits of the ruler, and posits that it might also be sourced from a series of representations of sea creatures caught in the act of emerging from the sea.

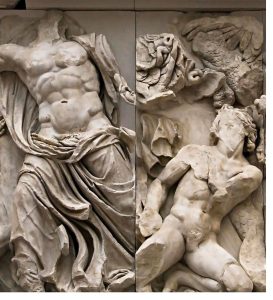

Scholars Francis Haskell and Nicholas Penny proposed that is might be “a fragment of some heroic narrative group,” while others suggest it might be a dying giant, comparing it to similar characters in the Great Altar of Zeus at Pergamon. Emerson saw the features and style of the Dying Alexander as being closely connected with the schools of Rhodes and Pergamum, reminiscent of the Laocoön and the Dying Gaul. He suggests that the giant depicted at the foot of Zeus in the Pergamon Altar—whose face is now lost—is actually the original source for the Uffizi’s Alexander, which was made before the giant’s face was destroyed. In his proposal, he created a diagram where he transposed the Uffizi bust onto the Pergamon giant, with convincing results – see below.

Where does that leave the Uffizi’s Dying Alexander? As a sublime copy – one which influenced the course of art history.

ABOUT THE AUCTION

We’re pleased to offer this Roman copy of the Greek original Dying Alexander in our Cabinet of Curiosities auction, online from March 25-30. Endlessly surprising, this auction is for those who relish all things rare and remarkable. We invite you to browse the full gallery on our website.

Please contact us for more information.

On View:

Sunday, March 26 from 12:00 pm to 4:00 pm

Monday, March 27 from 10:00 am to 5:00 pm

Tuesday, March 28 from 10:00 am to 5:00 pm

Note: This auction starts to close at 5 pm ET.

Related News

Meet the Specialist

Sean Quinn

Senior Specialist, Clocks, Sculpture & Lighting