“Painting was the only thing that mattered”

“Pictures are merely a by-product of the painter’s effort.

The important thing is the effort, the striving itself.”

– David Brown Milne

David Brown Milne was, according to eminent critic Clement Greenberg, among the three greatest artists of his generation in North America.

A.Y. Jackson called him a genius. His work merited enough notice that five of his pieces were featured in the seminal 1913 Armory Show in New York, one of only two Canadians, positioned alongside such titans as Matisse, Picasso, Braque, Léger, Derain, de Vlaminck, Kandinsky, Brancusi, Duchamp, Delacroix, Cézanne, Monet, Redon and Van Gogh.

Like many of the other artists in that 1913 Armory Show, Milne was a man who marched to the beat of his own drummer—that drummer being freedom, creativity, and the self above all else. When asked if he was a member of the Group of Seven, Milne replied that he “wouldn’t like to be more than one of one.” He was relentlessly true to his vision, despite crippling poverty and very little commercial success.

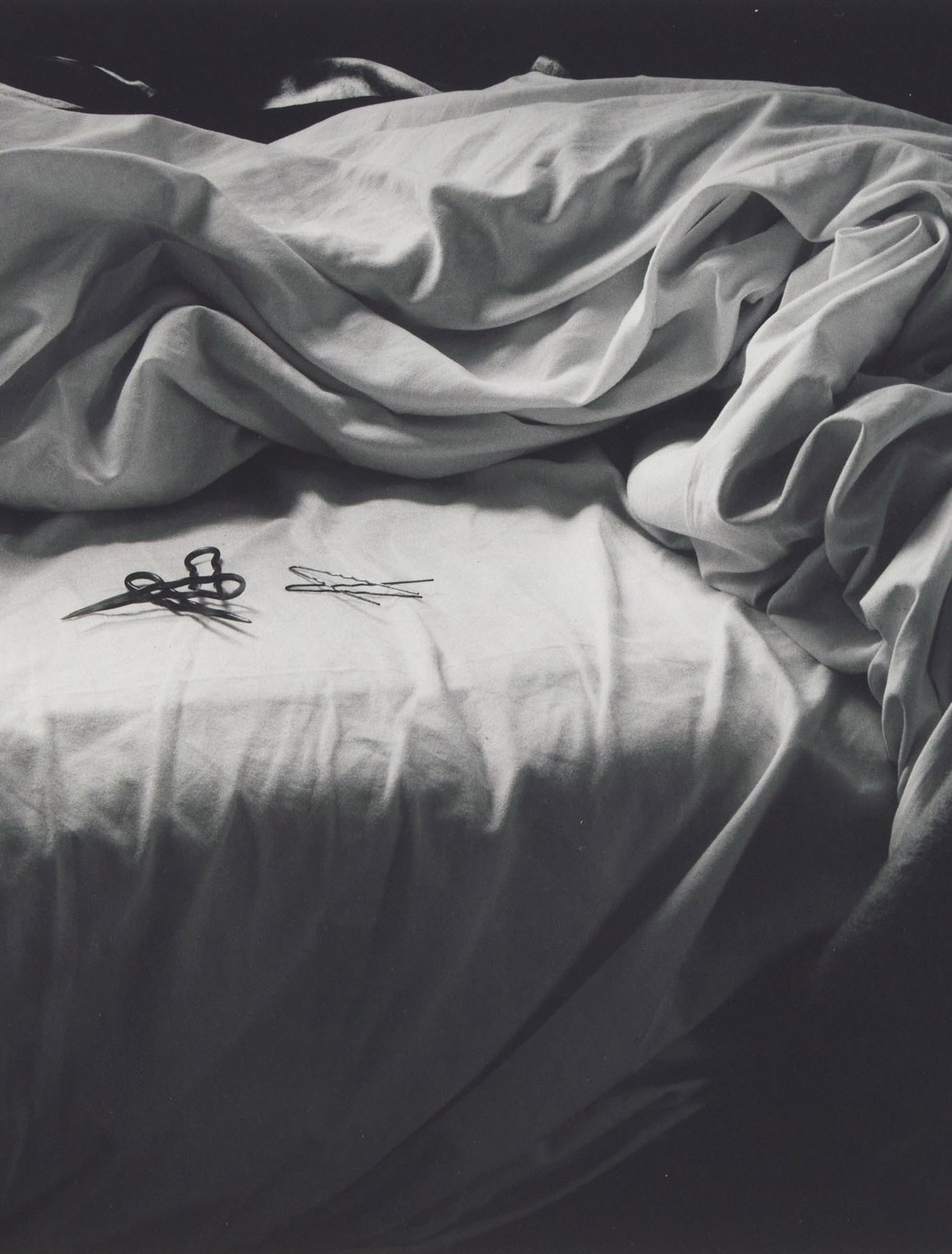

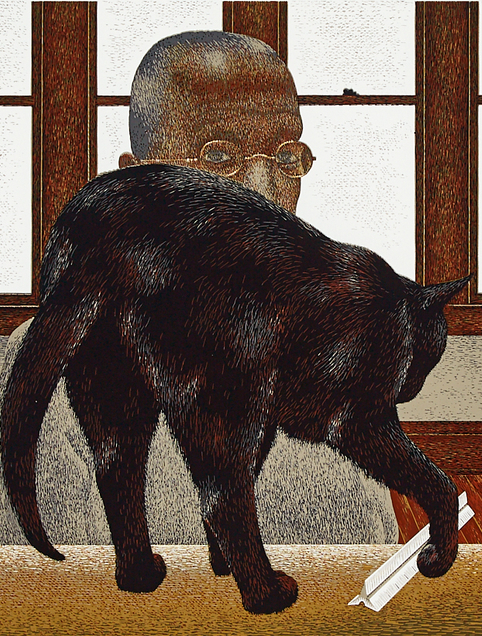

A colourful profile of Milne written by Barbara Moon in 1961 for Macleans magazine describes the man as “[looking] like a tanned squirrel in steel-rimmed glasses, who talked like a courtier, who lived with the thoughtless tyranny of a milord and to whom, quite simply, painting was the only thing that mattered.”

Milne’s Early Days

Born in 1882 in rural Ontario, the youngest of six children, Milne showed an early interest in art. A loan from one of his four brothers allowed him to pursue art in New York City at the Art Students’ League. He studied there for a brief stint, but soon became disillusioned. He stayed in the city for another eleven years and took on a series of odd jobs, one of which was as a window dresser. In this role, he met his future wife Patsy Hegarty. The two eked out a meagre living, leaving the city in 1915 so Milne could devote less time to working and more time to painting. When money ran dry, he would suggest Patsy get a job, he would borrow money from friends, or live off of the land. The couple travelled along the east coast of Canada and the United States, never staying anywhere too long. Success was elusive, and Milne made little off of his art.

A life changing Letter

In 1934, he wrote a letter to Vincent Massey, who was a noted art collector as well as a prominent political figure and lawyer. Milne, swinging for the fences, suggested that Massey should build a dedicated gallery to house Milne’s artworks, as well as provide him with an ongoing subsidy. Along with this missive, he sent along 250 paintings. On the matter of building a Milne museum, Massey demurred, though he did buy 300 paintings from the artist outright for a sum of $1500. He also provided Milne with an introduction to Mellors Gallery in Toronto, who promptly organized a show for the artist. The show was a success, and Milne sold several paintings. He used the cash infusion to decamp to the Muskoka region and build himself a small tarpaper shack. Patsy visited him a few times in his new seclusion, though in 1939, Milne wrote her a short five-line note suggesting that they get divorced. He explained to a friend that he could not afford a wife due to constraints of finances and time. Patsy never heard or saw him again, and Milne apparently lived the rest of his life in fear that she would try to visit him. Moon believes that “he came to count as too expensive anything — clothes, comforts, food, a house, a friendship, a marriage — that cost him painting time, or his poise.”

After a few more relocations and a few more cabins, Milne came to settle in the Haliburton Highlands, with Kathleen Pavey Milne, who would bear his only child, a son named David. A degree of success also came calling, with regular shows and a fixed income provided by Douglas Duncan, a gallerist who exhibited his paintings annually as well as augmenting Milne’s sales with personal purchases of his work. Duncan, along with Alan Jarvis (later the director of the National Gallery of Canada), were instrumental in creating interest and appreciation for Milne’s paintings. Milne painted until a series of strokes in 1952, which left his painting hand paralyzed. While he fully intended to relearn painting with his other hand so as to continue his work, he died shortly after in 1953.

Milne’s prolific career can be grouped into distinct categories – with each change of place and circumstance came bold thematic, chromatic and formalistic jumps. His visual vocabulary shifted vastly over the years, in possession of a mind through which, in the words of Megan Jenkins, “international visual idioms and Eastern Canadian wilderness coalesced into a Canadian modernism, important for its uniqueness and its innovation.”

Works by Milne in our September Auction

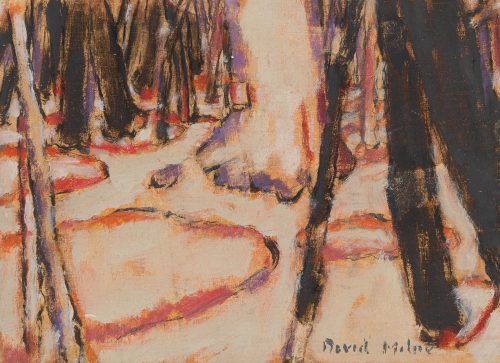

We are pleased to include three works by David Milne in our September 17th Canadian Fine Art auction, each rendered in a different medium.

Lot 11, “Sugar Maple”, originates from the collection of Milne’s most important patron, Vincent Massey. The work dates to 1935, shortly after Milne wrote his life-changing letter. Oil on canvas, the painting demonstrates Milne’s fascination with a restricted palette, a deliberate choice so as to increase emphasis on line and form.

Milne was a prolific writer as well, leaving behind countless notes about his painting process, his struggles, and his philosophy of art. He once wrote that “the thing that makes a picture is the thing that makes dynamite—compression.” Indeed, “Sugar Maple” is emblematic of this. Milne keeps the viewer’s gaze on the forest floor, focusing the eye on the way in which the bases of trees emerge from snow. The scene is tight, emotionally stirring, with the viewer surrounded and perhaps even lost in the deep woods. Milne’s use of the trunks to form strong diagonal lines is dynamic, imbuing a seemingly straightforward scene with power and vigour.

Lot 67, “Bush and Pasture”, is similarly spare. In an excellent essay, Dorota Kozinska notes that “[Milne’s] mission was to express the most with the least, and he refined the art of reduction. His gesture was marked by a Zen-like delicacy and precision, the form hinted at in just a few lines or patches of colour.” Milne’s second partner Kathleen noted on the back of this work that it was completed in Uxbridge. It is also inscribed on the back by Duncan, his gallerist. Duncan was so devoted to Milne’s career, that it caused another one of the artists he represented, the Slavic painter Paraskeva Clark, to once say of him, “agh. Duncan. With heem it’s all Meelne, Meelne, Meelne, Meelne, Meelne, Meelne!’’

The third lot, 59, is a colour drypoint of St. Michael’s Cathedral, located at the intersection of Bond and Shuter Street in downtown Toronto. Milne made 60 impressions of this print, though he destroyed seven of them. Only 53 and two unsigned proofs survived. This is also the last of Milne’s published prints, produced in 1943. Milne was an accomplished printmaker, which aligned closely with his love of process above content. While Milne could work magic with very little, this print takes a complicated subject—a neo-Gothic cathedral—and reduces it down to its very essentials. In the words of the artist himself: “pictures are merely a by-product of the painter’s effort. The important thing is the effort, the striving itself.”

Find out more

These works will be offered in our Canadian Fine Art Auction on September 17. For more information about the auction, previews and how to register to bid please click here.

We also invite you to take a closer look at the work of David Milne in our downloadable, digital Canadian Fine Art catalogue, alongside other excellent works by Canadian masters.

We are always available to answer any questions you may have, or provide condition reports and/or additional images.

Please do not hesitate to contact us at [email protected] or by phone at 416-847-6196.