Japanese Woodblock Prints in our Asian Art auction

The Origin of the Term “Ukiyo-e”

Our August Asian Art auction includes several examples of Japanese woodblock prints – we thought you might like to find out more about “ukiyo-e”.

Woodblock prints are referred to in Japanese as “ukiyo-e” (pronounced “oo-key-oh-eh”), which translates to “pictures of the floating world.” The word “ukiyo” was first used to explain the Buddhist concept of the transitory nature of life, specifically the sorrow and grief caused by the desire for earthly pleasures which blocked the soul from achieving enlightenment. During the Edo period (1603 – 1868), the Japanese character for the verb “to float” was swapped in for the homonym meaning “transitory,” so that the term “ukiyo” metamorphosed from “sorrowful world” to “floating world,” thus expressing a sort of lightness, hedonism and joie de vivre

The ukiyo culture found its ultimate manifestation in Yoshiwara, the red-light district of Edo (modern-day Tokyo), and the Kabuki theatre district, drawing inspiration from the denizens of this demimonde: prostitutes, geisha, sumo wrestlers, kabuki actors, samurai, as well as the growing lower and middle classes. Though the pursuit of pleasure was placed at the forefront, underlying the genre is an understanding that all of these worldly delights are fleeting—bringing the term “ukiyo” full circle once again.

The making of a woodblock print

In Japan, woodblock printing was in use as early as the eighth century, though the process was most commonly used to disseminate texts and Buddhist scripture.

Though ukiyo-e are typically attributed to a single artist, each print also requires the efforts of three additional players: an engraver, a printer and a publisher. Prints were seen as commercial ventures, and required the direction and backing of a publisher—often a bookseller—who was responsible both with dictating the theme and ensuring the quality of the edition. The artist would come up with a design within that commissioned theme, and render the work on paper. This design was then transferred to a thinner paper akin to drafting/tracing stock. Using this as a sort of stencil, the engraver would chisel the design into blocks of wood in negative, so that the lines meant to make an impression would be flush with the surface of the wood. Areas meant to be blank would be carved away. The printer would then lay pigment onto the surface of the wood. Paper would then be placed onto the still-wet ink, thus creating a print.

Printing was typically done on a traditional, locally made Japanese paper made from the mulberry tree, which was prized for having very long and strong fibers. Most of the pigments used in ukiyo-e are organic or mineral-based: for example, white is derived from ground shells, red from flower extracts, and so on. Shades that were not found in nature were imported, such as the Prussian blue hues that were brought from Europe during 1820’s and onwards.

By the middle of the 18th century, technology had advanced to a point where polychromatic woodblock prints could be produced. Several woodblocks were carved based on one preliminary sketch, with each block being used for a separate colour. As such, it can be assumed that an ukiyo-e print with 12 colours had 12 interdependent woodblocks involved in the printing process. Despite the complexity of this process, prints were made for large audiences, and were within reach of the middle class, which explains why there are a fair number that have survived to this day.

A concise history of ukiyo-e

The Department of Asian Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art explains that ukiyo-e prints can be seen as “the final phase in the long evolution of Japanese genre painting.” They note that the setting of these scenes transitioned from outdoor landscapes towards indoor activities, with a focus on the delights of city life. As noted above, depictions of the brothels and pleasure houses of the Yoshiwara district were massively popular, especially around the early 17thcentury. Actresses and courtesans were promoted heavily, and particular detail was paid to their outfits and changing fashions. These images were sought out by visitors to Edo as both art and souvenir, becoming known as “Edo pictures.”

Government reforms passed in the 1840’s aimed at supressing outward displays of luxury meant that artists shifted their gaze away actors and women and towards landscape views. Two of the best-known ukiyo-e artists, Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858) and Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849), designing within this landscape genre, have come to define ukiyo-e images in the Western imagination, though this ignores the breadth of subject matter that preceded their work.

The death of these two masters, combined with a desire to Westernize and modernize Japan, ushered in the decline of ukiyo-e as a dominant artform. The shogunate was abolished in 1867, and for a time, printmaking seemed to disappear along with it.

Though production waned in Japan, the 1860s ushered in the Japonisme movement in Europe. Western artists and collectors became fascinated by the colours, composition, perspective and techniques used in ukiyo-e, strongly influencing the work of artists like Edgar Degas, Édouard Manet, Claude Monet, Vincent van Gogh and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

Determining value

After condition, quality and authenticity are taken into account, two major factors matter when evaluating the value of ukiyo-e prints: popularity and edition number. Understandably, work by master artists like Hiroshige and Hokusai are in high demand, which keeps prices high. Certain subjects and series are also extremely popular, such as Hokusai’s suite of prints, “Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji,” which contains “The Great Wave off Kanagawa,” one of the most instantly recognizable images in the world.

Early prints hold a higher value for collectors than later reproductions, as the initial impressions were supervised by the artist and publisher. The quality of early prints is often higher: details are often finer and colours may even be more unique. In later prints, the mark of the woodblock becomes visible, and outlines may lose their definition as the blocks become well used.

High quality Japanese wood block prints remain highly collectible both in Asia and the West. Young Chinese collectors are also becoming extremely attracted to the artform, and an increase in interest from the region has been noticed over the past few years. Museum-quality prints have performed well at auction—an ukiyo-e print by Kitagawa Utamaro fetched €745,000 in Paris in 2016.

AUCTION INFORMATION

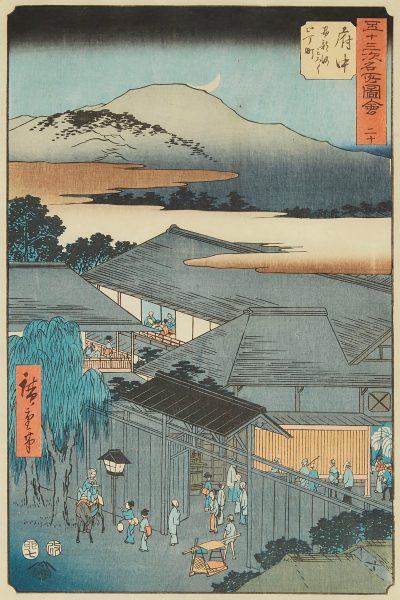

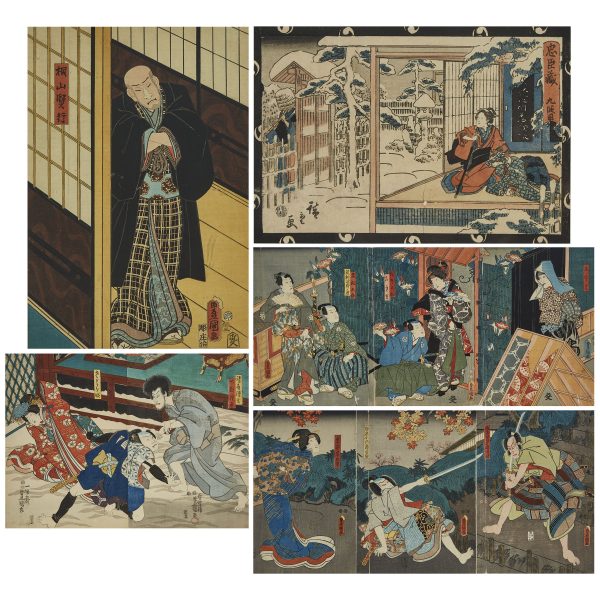

Our August Asian Art auction includes several examples of ukiyo-e prints—including a group of five by Hiroshige and Kunisada—(see below) alongside various paintings and decorative objects.

We invite you to view the full gallery.

This auction is offered online August 22 – 27; the auction begins to close at 2 pm ET. Please note that all transactions are in Canadian Dollars (CAN).

Contact Us for condition reports, additional photos or information. Whether you are based in Canada or abroad, we are here to serve you by telephone, email or secure video link.

Related News

Meet the Specialists

Austin Yuen

Specialist

Amelia Zhu

Senior Specialist / Business Development