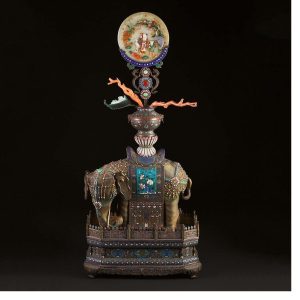

清 嘉庆(1796-1820) 鎏金铜胎掐丝珐琅嵌宝’太平有象’摆件

Brightly coloured and intricately detailed, cloisonné is an elite art which reached its greatest heights in China during the Qing dynasty (1636-1912). Complex in technique and dazzling to the eye, the art form remains highly sought after by collectors to this day.

OBSCURE BEGINNINGS

Cloisonné was invented outside of China, first appearing in the Mediterranean basin around 1500 BCE. Its zenith in Europe occurred during the Byzantine Empire, between the eighth and fourteenth centuries. The origins of the technique’s introduction to China remain obscure owing to a lack of historical sources, though it is suggested that the cloisonné was imported by Islamic people immigrating to the province of Yunnan from Byzantium. The earliest agreed-upon example of Chinese cloisonné is dated to the reign of the Ming Xuande emperor (1426–1435), though some scholars date unmarked examples as far back as the previous Yuan dynasty or the Yongle reign (1403–1424) of the early Ming dynasty.

THE CLOISONNÉ METHOD

The word “cloisonné” comes from the French, and means “walled enclosure.” Though its roots are foreign, Chinese craftsmen employed the technique to great effect. To make cloisonné, copper or bronze wires are shaped to form small enclosed spaces known as cloisons (“partitions”), which are then soldered or pasted onto the surface of a metal object. These small spaces are then filled with different colours made from glass paste mixed with metal oxides. This mixture, when fired at a relatively low temperature (below 800°C), hardens into enamel. Enamel shrinks when heated, so the process is repeated several times to ensure that there are no gaps in the cloisons. Once all of the areas have been completely filled, the object’s surface is pumiced and buffed to reveal the edges of the cloisons and to render the surface smooth and glossy. Gilding will then be applied to the finished product.

AN ELITE ART

By the reign of Xuande in the 15th century, cloisonné was highly valued, and was even used to decorate the Imperial throne room. Early examples of cloisonné are exceptionally rare, but as the art form became more sought after, more workshops were established, resulting in greater production. This had the effect of increased experimentation and creativity, and by the 16th century, new, brighter colours were introduced—red, ginger yellow, sky blues, pale greens, soft purple and waxy white—which mirrored contemporary tastes in other art forms, such as porcelain. Works from this period were often lighter and featured repetitive motifs, effected in a bid to make the art form more accessible.

That said, cloisonné is exceedingly complex, precise and time consuming to make, which resulted in expensive objects out of the reach of the average consumer. These objects were made largely for display in temples, palaces and the spaces of the elite—and were seen as too flamboyant for the more sober atmosphere of a scholar’s home. Unlike the monochrome palette of Chinese lacquerware, cloisonné is prized for its rainbow hues. Dazzling luxury was its aim, and it has been compared with the French Rococo style for its similar lavishness.

Designs and shapes often borrowed from antiques and artifacts, but through the cloisonné technique, were rendered in technicolour hues unknown in the originals. These older forms were seen as emblematic of China’s great and ancient civilization, and despite the great cost of producing cloisonné, were more accessibly priced than the original antiques.

AN ARTISTIC GOLDEN AGE

After the collapse of the Ming dynasty in 1644, the Qing dynasty rose to power. The Kangxi Emperor (1661–1722), the third emperor of the Qing dynasty, and the second Qing emperor to rule over China proper, established imperial workshops within the Forbidden City, which produced porcelain, enamel and cloisonné objects for the court’s use. Kangxi’s son Yongzheng was also a great patron of the arts, though he favoured enamel and porcelain over cloisonné.

Cloisonné perhaps reached its peak during the reign of Qianlong (1736-1795). He especially loved the art form, commissioning vast quantities of cloisonné and establishing more workshops on the palace grounds. In his desire for more luxury, he supplemented his collection with enamels produced in the Guangdong province in southern China. Quality soared, and new colours were introduced, allowing artists a range of more than twenty colours, including greens, pinks, black, lilac, and orange.

The reigns of Kangxi, Yongzheng and Qianlong are often referred to ‘the golden age of three emperors,’ a period of great wealth and power. Béatrice Quette, a Chinese art historian and President of the Oriental Ceramic Society of France, notes that “the imperial tradition of Chinese emperors collecting and commissioning the finest art started during the Northern Song dynasty (960–1125) and reached an apogee with the three Qing emperors.” She continues, “after his grandfather and father, Qianlong was undoubtedly the greatest collector of Chinese art and the greatest promoter of artistic production in Chinese history.”

ABOUT THE AUCTION

Waddington’s is pleased to offer examples of this exquisite art form in our major Asian Art auction, online from June 4-9.

The auction centres around an imperial 18th/19th century gilt-copper and cloisonné caparisoned elephant, ‘taiping youxiang’ 太平有象.

Other Chinese art highlights include Ming and Qing white jade objects, Han and Tang bronzes, Qing and Republican period porcelain, late Qing and modern Chinese paintings, imperial Chinese embroideries, and two Buddhist stone steles certified by Martin Fung.

Japanese works of art include a beautiful gilt painted floor screen attributed to Kano Shoei (1519-1592) and a sculpture of Jizo Bosatsu from the Kamakura to Momoyama period (14th-16th century). Also included are selections of Himalayan and Indian bronzes, Southeast Asian sculptures, and Persian Safavid ceramics.

我们很高兴为您呈现本年度第一场沃丁顿重要亚洲艺术品拍卖。中国艺术品板块由一只清中期官造18世纪/19世纪鎏金铜胎掐丝珐琅’太平有象’摆件所领衔, 包含一批工艺精美、传承有序、材料优良的明清白玉与翡翠器皿,汉唐金铜造像,清至民国时期精品瓷器,晚清/近现代中国书画,中国皇家织绣品和佛教石刻。日本艺术类包含一扇由Kano Shoei(1519-1592年)制作的描金六开落地屏风和一尊镰仓/桃山时代(14至16世纪)的地藏菩萨立像,年代久远、品相完好。其他精选拍品包含喜马拉雅艺术,东南亚雕塑造像,以及本地拍场较罕见的波斯萨法维陶瓷。敬请期待!

Please contact us for more information, condition reports, or for additional images.

Related News

Meet the Specialists

Amelia Zhu

Senior Specialist / Business Development

Austin Yuen

Specialist