Female authors have historically faced prejudice in the publishing world, with their writing being seen as ‘unserious’ and not the stuff of high art, pushing many women to write under male pseudonyms in order to be taken seriously. We are pleased to present first editions by two of the most famous examples, Emily Brontë and Mary Anne Evans, respectively known to their readers as Elias Bell and George Eliot, in our Cabinet of Curiosities auction.

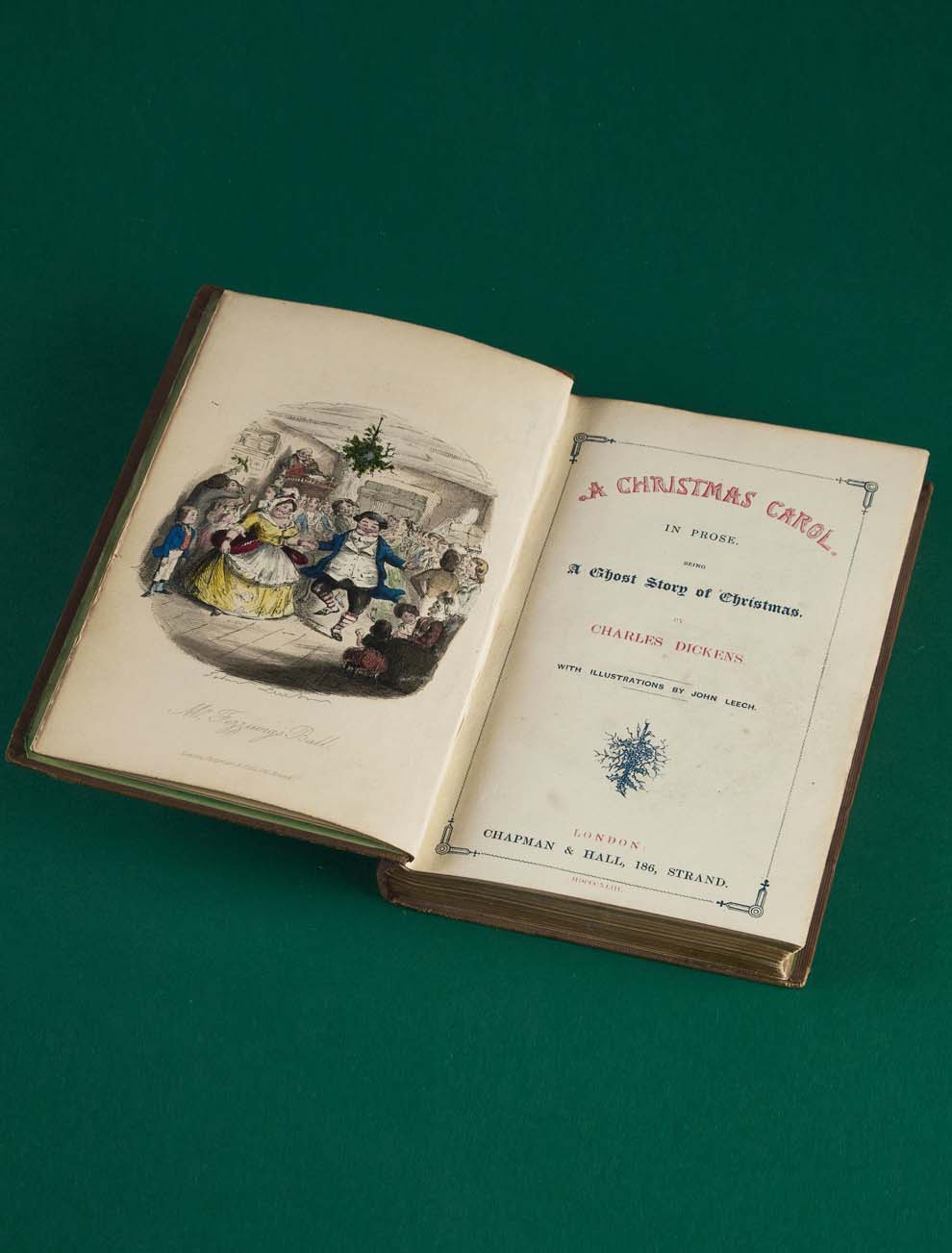

EMILY BRONTË’S WUTHERING HEIGHTS

Raised in Yorkshire, Emily (1818–1848) and her siblings led an isolated childhood, finding refuge in literature, creative pursuits and imaginary worlds. In 1845, a private book of Emily’s poetry was found by her sister Charlotte. Charlotte, as well as sister Anne, had also been secretly writing poems, and convinced Emily to join them in seeking a publisher for a collective anthology of their work.

Charlotte, perhaps the most ambitious of the sisters, had been looking to have her work reach a wider audience for some time. She had written to poet Robert Southey in 1836 to ask his opinion of her writing, to which he had replied that “literature cannot be the business of a woman’s life: and it ought not to be.” It was thus decided that all three Brontë sisters—Emily, Charlotte and Anne—would submit their poems to a publisher using male aliases. They chose the pseudonyms Ellis, Currer, and Acton Bell, selecting initials which mirrored their own. Charlotte explained that “the ambiguous choice [of names] being dictated by a sort of conscientious scruple at assuming Christian names positively masculine, while we did not like to declare ourselves women, because—without at that time suspecting that our mode of writing and thinking was not what is called ‘feminine’—we had a vague impression that authoresses are liable to be looked on with prejudice.”

The book of poetry attracted little attention and sold only a handful of copies. Yet it inspired the sisters to begin writing novels, and all three had produced a complete work within the year—Charlotte’s Jane Eyre, Anne’s Agnes Grey, and Emily’s Wuthering Heights.

The sisters knew that their subject matter would be viewed as coarse and unfeminine by their Victorian readers, featuring as they did strong sexual themes, harsh language, substance abuse, and violence. Using a male alias would mitigate these issues, while also preserving the anonymity and peace of the Brontë’s personal lives. So insistent were they on preserving their privacy that even the sisters’ publishers were kept in the dark as to the true identity of their authors. Only when an American publisher suggested that Agnes Grey and Wuthering Heights had been penned by the same author who has written Jane Eyre did the sisters out themselves as three distinct—and female—authors.

When Wuthering Heights was published in 1847, it received poor reviews, seen as brutish and clumsily constructed. While it was acknowledged as a ‘powerful’ book, the mental and physical cruelty of its hero, Heathcliff, deeply disturbed Victorian readers. Emily would die just one year later, not living long enough to see the magnetic appeal that her novel would have for subsequent generations. It was Charlotte who would introduce Emily to the world, writing two posthumous prefaces to accompany subsequent editions of Wuthering Heights that form the basis of what we know about the author herself. Charlotte describes her sister as “stronger than a man, simpler than a child” and her only published novel as “moorish and wild, and knotty as the root of heath.” Years later, Wuthering Heights would come to be seen as one of the greatest books ever written in the English language.

7 x 5 in — 17.8 x 12.7 cm

Estimate $600-$800

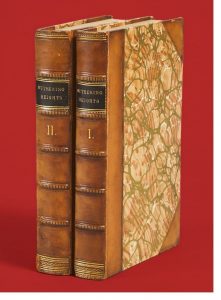

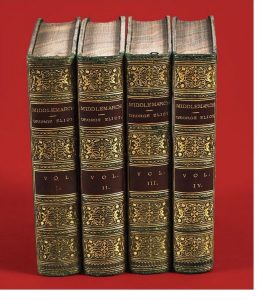

GEORGE ELIOT’s MIDDLEMARCH

Unlike the more isolated lives of the Brontë sisters, Mary Anne Evans (1819-1880) would live a much more public life. Born in Warwickshire, she would eventually settle in London after the death of her father in 1851. For years she contributed to The Westminster Review, a radical philosophical journal. Her position as a female journalist was highly unusual for the time, made possible by the inheritance left to her by her late father. When she began writing novels, however, she made the same decision as the Brontë sisters, choosing to publish under a male pseudonym to avoid the stereotypes afforded to female authors.

Before publishing her fictional work, Evans had begun what would become a decades-long relationship with the married journalist George Henry Lewes. She borrowed his first name for her alias, and chose ‘Eliot’ as it was “a good mouth-filling, easily pronounced word.”

In 1859, at the age of 39, Evans published her first novel, Adam Bede. It was an instant success, and made George Eliot a household name. The public’s fascination with the work fostered intense curiosity as to the identity of this mysterious author. A man named Joseph Liggins stepped forward, claiming to have authored Adam Bede and a few short stories that Evans had published serially. Although initially amused, Liggins’ behaviour soon prompted Evans to step forward and take proper credit for her work.

Evans popularity as a novelist increased with the release of The Mill on the Floss, and subsequent novels including Middlemarch, Silas Marner and Daniel Deronda. Despite her massive popularity, Evans and Lewes were shunned from society events due to the unorthodox nature of their relationship. Lewes was, through a bizarre legal loophole, unable to divorce his wife for Evans, meaning that they lived as husband and wife in name only. Acceptance would only arrive when they were invited to an audience with Princess Louise, the daughter of Queen Victoria, both royals being avid fans of Evans’ writings.

Middlemarch, like Wuthering Heights, received mixed reviews upon its debut. Criticized for being overwrought and melancholic, it was only in the 20th century that it began to be seen as a masterpiece. Virginia Woolf described it as “one of the few English novels written for grown-up people,” with contemporary critics consistently listing it among the greatest novels ever written.

FIND OUT MORE ABOUT THE CABINET OF CURIOSITIES AUCTION

We invite you view the full auction gallery here. The auction will be offered online from July 3-8, 2021.

Previews by appointment will be available, please contact Sean Quinn to schedule an appointment.

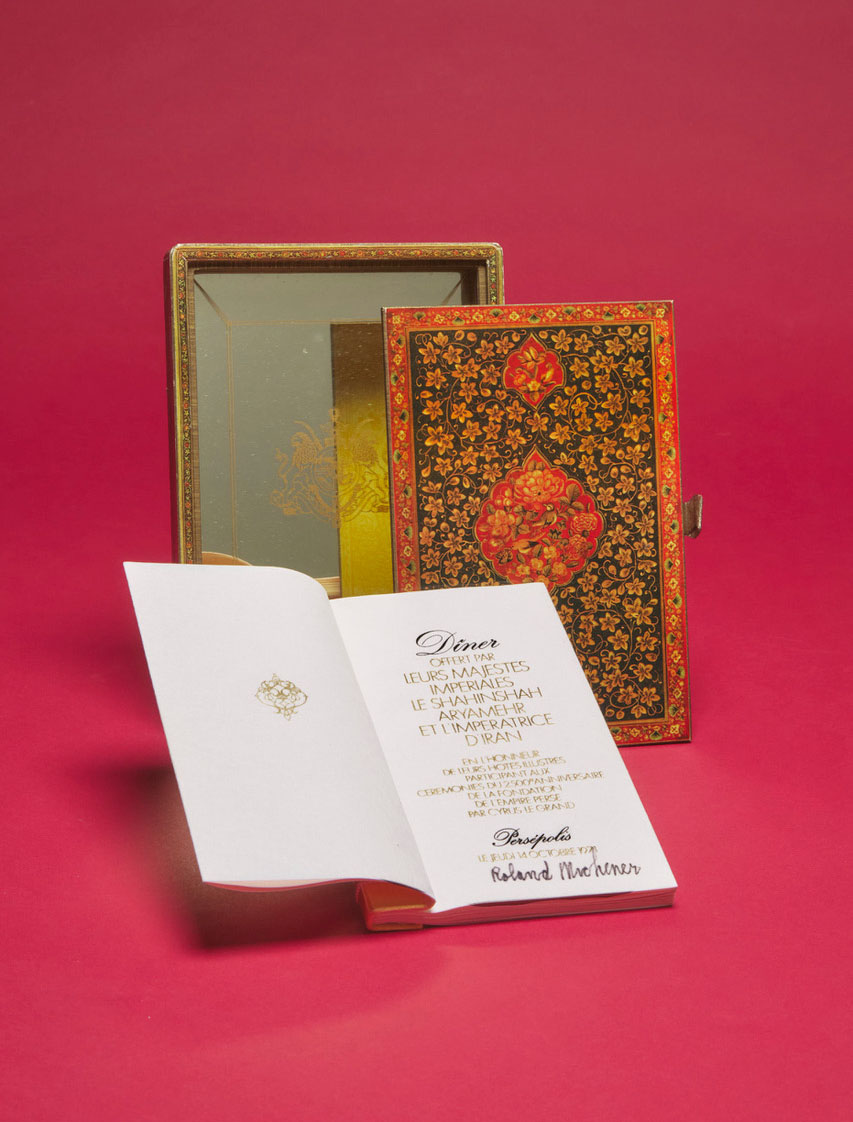

Endlessly surprising, this auction is for those who relish all things rare and remarkable. Anglophiles will appreciate a book signed and presented by Queen Victoria, as well as a tiger claw mounted silver desk stand presented by her son, the future King Edward VII.

Bibliophiles should also take note of a library of 17th-20th century books on Witchcraft and the Occult.

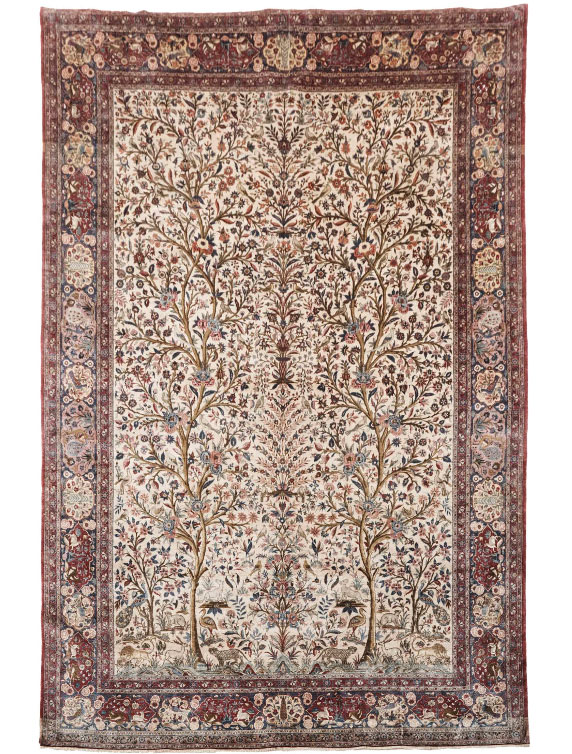

This diverse auction also includes offerings from the categories of Weaponry, Islamic and Indian Art, World Cultures, Ancient Civilizations, Ecclesiastical Art, and Science and Technology.

Should you have any questions or would like additional images or information, please do not hesitate to contact Sean Quinn at [email protected] or by telephone at 416-847-6187.

Related News

Meet the Specialist

Sean Quinn

Senior Specialist, Clocks, Sculpture & Lighting