Adjustable height 23 in — 58.4 cm, length 34 in — 86.4 cm.

Estimate $500-$700

When Decorative Arts specialist and connoisseur of all things weird and wonderful Sean Quinn told us that he had Sir Frederick Banting’s polarimeter, we needed to take a closer look. From rare books to historical dog collars and letters by luminaries, Quinn has a talent for finding some of the most interesting and exceptional items on the market.

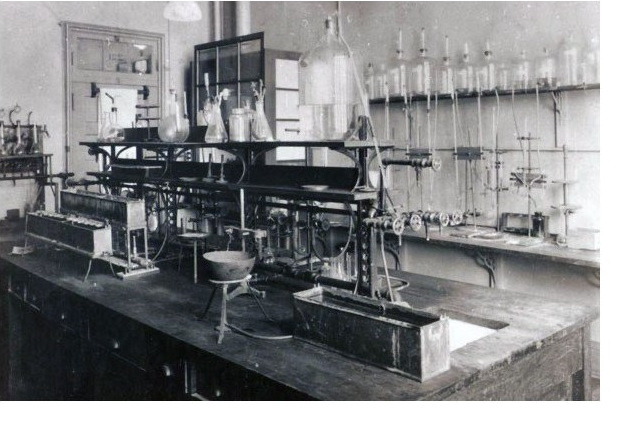

The discovery of insulin in 1921 is one of the most significant medical advances of the 20th century. The men responsible for this achievement—Dr. Fredrick Banting, Dr. Charles Best and Professor J.J.R. Macleod—did their experiments in a laboratory in the Faculty of Medicine Building at the University of Toronto. Lot 425 in the Canadian Arts, Culture and History auction (December 4–9) is a polarimeter, a piece of equipment which came from that very lab.

What is a polarimeter?

Polarimeters are used in chemistry, primarily in the identification of unknown substances. For many substances, common identifiers like the melting or boiling point are not always achievable or distinct enough to allow scientists to make definitive conclusions. Where substances do differ is in their optical activity, or their unique angles of rotation when a polarized beam of light is passed through them. Depending on the substance, the light will be seen to rotate either clockwise or counter-clockwise and on a specific angle.

Wait—what is polarization?

Polarization is a compressed light wave. Regular light, such as sunlight, travels in an S-shape, vibrating up and down as it moves forward. These S-shaped vibrations can be vertical, horizontal, or assume a shape in another angle. When light is polarized, it vibrates at only one angle.

Polarization can be created by passing light through a filter. A polarizing filter has its molecules aligned in the same direction, which blocks all waves that do not align with than angle, creating a “one-direction” beam. BBC Science uses the metaphor of a skipping rope passed through the posts of a picket fence. Any attempts to move the rope will be thwarted unless that movement is up and down. Side to side movement will be blocked.

This has the effect of reducing the light’s intensity, which is why the technique is commonly used to make sunglass lenses which reduce brightness and glare.

The history of the polarimeter

The effects detailed above were first noticed by Etienne Malus (1778-1812), a French officer, engineer, physicist, and mathematician. In 1808, when studying the effects of double refraction, he examined the reflection of the setting sun in a window by looking through a calcite crystal known as Iceland Spar. When the crystal was rotated, the sun’s image became stronger or weaker.

In 1812, Jean-Baptiste Biot (1774-1862) noticed that the extent of a light beam’s rotation depended on the thickness of the quartz plates he was using as a filter. Another discovery of his was that the light’s rotation could be changed with the introduction of turpentine and sucrose solutions. Biot was able to conclude that optical activity is related to the structure of chemical compounds. Using these findings, Biot began formulating the basic quantitative laws of polarimetry and designed one of the first polariscopes.

Louis Pasteur (1822-1895), a chemist best known for his discoveries about vaccination, microbial fermentation and, of course, pasteurization, continued Biot’s work. Pasteur studied the optical activity of crystal forms including tartaric and racemic acids using a polarimeter, and was able advance the field of polarimetry.

How is it used today?

While you might be thinking that a polarimeter is only used by a very specific group of scientists, polarimetry is actually used in quality and process control in industries handling pharmaceuticals, food, flavour production, fragrance and essential oils, and of course, chemicals. The sectors are concerned with purity, and the varied substances that they produce and handle must be compared with reference values.

Banting, Best and Macleod’s Polarimeter

Prior to studying medicine, Dr. Stanley Gore, an Honours Science undergraduate at the University of Toronto (1966-1970), worked as a biochemistry research student in Professor Jeffrey Wong’s lab in the original Faculty of Medicine building. This historic campus structure, adjacent to the land occupied by the current Faculty of Medicine Building, housed the Departments of Physiology and Biochemistry. Shortly before the building was scheduled for demolition, staff, graduate and research students were invited to take one or two instruments as mementos. Dr. Gore selected this polarimeter from the laboratory used by Macleod, Banting and Best.

About the discovery of insulin

This year—2021—marks 100 years since insulin was discovered. One of the greatest medical breakthroughs in history, insulin has saved millions of lives. Diabetes had been diagnosed by doctors for centuries, usually through a high concentration of sugar in the patient’s urine. This inability to process carbohydrates and other nutrients and was generally thought of as a disorder of the stomach or liver. By the end of the 19th century, two German researchers, Oskar Minkowski and Josef von Mehring, had noticed that dogs whose pancreas was removed often developed rapid and fatal diabetes, leading them to conclude that it was something in the pancreas which protected against the disease.

Scientists began attempting to isolate this mysterious pancreatic substance. They reached the conclusion that clusters of cells called islets were what produced insulin, but were unable to extract it from the body.

The son of a farmer from Alliston, Ontario, Banting had served in the First World War, and was earning extra income teaching part-time in the physiology department at the University of Western Ontario while he started up his medical practice. While preparing for a lecture on the pancreas, Banting read that islets were slower to deteriorate than other pancreatic tissues, which gave him the idea that the pancreas could be broken down in a way that would leave the islets intact. He jotted down his idea, and took it to his colleagues at the university.

Banting’s colleagues suggested he take the idea to Macleod, who was running a lab at the University of Toronto which specialized in carbohydrate metabolism. Macleod doubted both Banting’s ideas and his skills as a researcher, particularly as Banting had no background in the field. However, with a surplus of resources and volunteers, Macleod decided to give Banting space in his lab, as well as an assistant—Charles Best, who won the position in a coin toss. The two would begin their work on 17 May 1921, under Macleod’s supervision.

By 30 July, Banting and Best were able to alter the blood sugar of a diabetic dog by injecting it with the extract of a degenerated pancreas from another dog. Soon they were able to produce the same extract from the pancreases of pigs and cows taken from the local slaughterhouse. By November, they had successfully treated a diabetic dog for 70 days using their substance.

By mid-December 1921, James Collip, a biochemist, joined the team. His task was to purify Banting and Best’s crude and inconsistent pancreatic substance so that it could be safely tested in humans. January 1922 marked the first human trial, as the team’s extract was injected into a thirteen-year-old diabetic boy, Leonard Thompson, who lay dying at Toronto General Hospital. Within 24 hours of treatment, Thompson’s blood sugar had dropped, though other blood markers for the disease remained high and an abscess had developed at the injection site. Collip worked furiously to refine the extract even further, and a second injection was given to Thompson 12 days later.

Collip’s purification techniques were a success, and Thompson’s blood sugar regulated without any harmful side effects. The team knew they were on the right track, and began expanding the scope of their research. In May 1922, Macleod presented their research, “The Effects Produced on Diabetes by Extracts of Pancreas,”at a Washington, DC convention of the Association of American Physicians. It was in this paper where the word “insulin” was first used—and was first introduced to the world.

About the auction

Representing diverse interests from coast to coast to coast, our Canadian Arts, Culture and History is available for online bidding from December 4-9, 2021.

We invite you to browse the full catalogue.

The auction includes a collection of Grenfell Industries hooked mats, John A. Macdonald’s mortgage for a farm in Hastings, ON, works by RCAF WWII artist George Broomfield, a library of volumes relating to Northwest Passage and Arctic exploration, early photography of Fort William (now Thunder Bay, ON), a Newfoundland passport, a pair of 18th century portrait miniatures of a St. John’s Newfoundland couple, a Métis Assomption sash, and a polarimeter from Frederick Banting’s lab at the University of Toronto. The auction also includes an extensive archive of documents of historical and political interest.

Please contact us for more information and to schedule a preview appointment.

Related News

Meet the Specialist

Sean Quinn

Senior Specialist, Clocks, Sculpture & Lighting